Thousands of Years of Poop Science Prepared Humans to Master Gut Flora Gardening

We've always understood that our waste can tell us about ourselves.

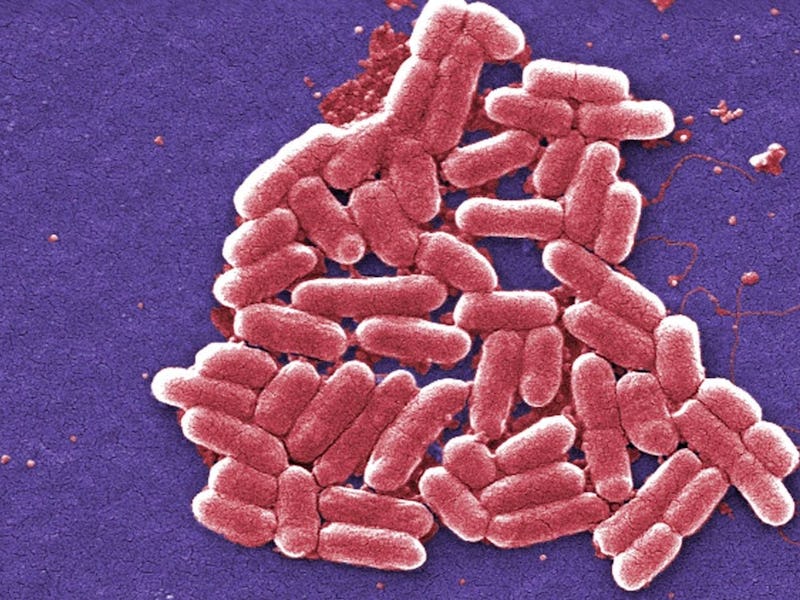

A good shit is absolution in its purest form and a uniquely smelly sort of introspection. Because the 100 trillion poop-making bacteria living in our guts strongly influence our physical and psychological wellbeing, our feces is material evidence of who we are as people at any given moment. And there seems to be a level on which we’ve always known this. Long before learning about salmonella and shigella bacteria, humans intuited that what ails us and what heals us can be found in what we leave behind.

The ancient Egyptians were the first to document the glories of bowel movements — and the hazards of irregularity — in a medical context. A pharmaceutical text dated to the 16th century B.C.E. defined disease as “a poisoning of the bodies from the inside.” The Egyptians, by drawing an instinctive link between bad smells and poor health, developed a paradigm that shaped medical theory for the next 3,000 years: Disease started in the gut, and expelling it — whether through puking, sneezing, or dropping deuces — was the best way to get healthy. Anal retentiveness led to death.

Louis XV, patient to the French physician Joseph Lieutaud, was likely instructed to poop out his depravity.

The 2,000-year-old remains of a massive Roman bathroom, analyzed by archaeologists in 2014, suggested that the fear of poop continued into ancient history. In Rome, public toilets were intimate, multi-user affairs — these were long stone benches, lined with 50 holes less than two feet apart — in the city’s underbelly, far beneath its opulent palaces. Researchers have argued that the lack of graffiti in areas around latrines suggests that they weren’t exactly popular hangouts, probably because they were (correctly) believed to be cesspools of evil and death. The rumor that one could get blown up by a spontaneous methane explosion, caused by the buildup of human sewage, only fanned the fecal flames.

Perhaps it isn’t all that surprising that so many societies feature “toilet demons” in their cultural mythologies. The Roman latrines featured small shrines to the goddess Fortuna, who was thought to offer protection from illness-causing ghouls. Ancient Babylonians believed in the demon Sulak, a toilet-dwelling lion standing on its hind legs that brought illness down on people at their most vulnerable moments. Likewise, the Judeo-Christian baddie Belphegor — demon of discoveries, inventions, and laziness — was appeased by offerings of human excrement. Like all demons, he fed on sin.

The Judeo-Christian toilet demon Belphegor was the embodiment of the classic clapback "eat shit."

The medical practices of the next couple of millennia did nothing to ease the minds of the constipated. In France in the 1700s, Louis XV’s personal physician, Joseph Lieutaud, echoed the idea that disease and the general unhappiness that stemmed from it was the result of a “depraved gut” in his Synopsis of the Universal Practice of Medicine. He went on to ascribe the utmost importance to getting rid of “the depraved juices, putrid matter, or depraved bile itself, lodged in the stomach and intestinal canal.” Lieutaud’s emphasis on widespread “depravity” suggests that the ills society ascribed to fecal matter were not just physical but moral; the scientific evidence demonstrating the gut’s connection to psychological illness and behavior, however, was still nearly three centuries away.

In the meantime, the concept of “autointoxication” — that is, death by accumulated poop — continued to be a guiding principle in the clinics of physicians across Europe and the Americas. Fears of constipation became especially pronounced with the dawn of industrialization. Because of increased urbanization, people were moving less and eating worse, resulting in bad bowel movements. It wasn’t long before constipation was nicknamed “the disease of civilization,” which was (and still is) oddly apt. An 1850s health manual quoted by Whorton instructs its readers that “daily evacuation of the bowels is of the utmost importance to the maintenance of health.” Without the daily movement, it warns, “the entire system will become deranged and corrupted.” Those systems weren’t just physical but psychological; disease emanating from the gut was believed to cause infections that, in turn, triggered mental ills like depression, anxiety, and psychosis.

Laxatives, like colonics and bowel surgeries, became popular in the Industrial Age as constipation became equivalent to disease.

Unchallenged for centuries, the autointoxication paradigm made room for an entire industry devoted to mechanisms for pooping better and living happier. The 19th century and early 20th century ushered in an era of laxatives, colonics, and, for the badly clogged, bowel surgeries. But these procedures weren’t designed just to maintain physical health: Because the link between butt, gut, and brain made so much sense intuitively, the colon-clearing methods were, in a sense, also a form of mental health treatment.

Physicians gave up on the idea of autointoxication once they discovered germs. Disease, they realized, wasn’t caused by the increasingly foul decay of pent-up waste inside the intestines but by microscopic bacteria and viruses invading the body. But they were too quick to give up on the connection between healthy poops and healthy brains: We now know that digestion relies on the activity of the microbiome — the mostly “good” bacteria that settle in our lower intestines — and that manipulating the cultural makeup of those colonies — whether through the use of antibiotics, probiotics, or poop transplants — has very obvious effects on physical and mental health. Recent studies have drawn links between autism and depression and the gut’s microbiome; others have shown that feeding mice with certain bacteria can reverse autism-like figures.

Like all old wives’ tales, the idea that “all diseases start in the colon” is pithier than it is accurate, but it does contain a kernel of truth. The aphorism, rooted in a mixture of objective truth and human instinct, illustrates that what we intuit to be true about ourselves has a scientific explanation at its core. In other words, it tells us what we’ve known all along: Go with your gut.