The DRACO Indiegogo Campaign Could Save Us From Viruses, but No One Will Pony Up

Todd Rider is asking for the internet's help to save mankind. It's not going well.

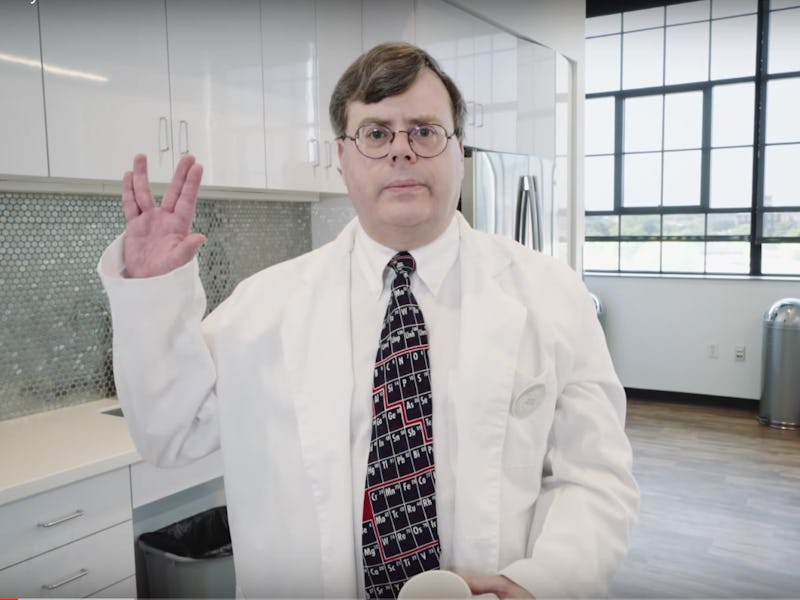

A biomedical engineer has discovered something that could one day cure all viral infections, and he has turned to the crowdfunding platform Indiegogo to pay for continued research. Todd Rider’s technology, called Double-stranded RNA Activated Caspase Oligomerizer, or DRACO, has already proven effective in lab tests against 18 viruses, including strains of the common cold, flu, and dengue fever. Rider hypothesizes that DRACOs could one day offer a cure for chickenpox, herpes, Zika, and even HIV. “Surely,” you say, “there must be a bum rush to fund this great humanitarian.”

Nope. Rider is currently about a month into a two-month campaign and he’s raised roughly $17,000 of the meager $100,000 he’s soliciting. And institutional funding hasn’t exactly spilled forth. In fact, Rider turned to the crowd because research organizations and pharmaceutical companies have shrugged off his potentially world-changing innovation. This is curious because Rider’s credentials check out. He’s a trained biomedical researcher, an MIT engineer, and a Harvard Medical School regular. He invented DRACOs 15 years ago, and has eked out a steady stream of positive (though preliminary) results ever since. He is not a nutcase and his idea makes inherent sense. DRACOs work by seeking out RNA produced by viruses inside the cells they have infected. If found, the DRACO binds to it and activates a suicide switch, killing the cell. Healthy cells are left unharmed, and before long the infection is eradicated.

The slow speed of research has to do with money. University medical researchers largely fund discovery through grants from funding organizations like the National Institute of Health. These relatively small allocations pay for proof-of-concept type work — the sort of basic research that is necessary to stumble upon major breakthroughs. But getting from breakthrough to new drug is a long and expensive road. Pharmaceutical companies typically aren’t interested in even the most promising early discoveries — they are considered too high-risk until a great deal more research has gone into proving that they can be developed into effective, safe, and marketable medicines.

This gap, between research that the National Institute of Health will pay for and research pharmaceutical companies will pay for, is known as the “Valley of Death,” where the vast majority of promising medical discoveries that make up daily headlines languish indefinitely. About 800,000 medical research papers are published annually and just 21 new drugs were approved in 2010, according to the New York Times. Pharmaceutical companies would rather not bet on promising early discoveries, especially when the intellectual property belongs to someone else, which reduces potential profitability significantly. And so Big Pharma focuses instead on patenting small tweaks to existing medicines.

The big question that remains is to what extent the public can (or will) step in to close the gap. In about eight months of crowdfunding over two campaigns, the RIDER Institute has attracted just over 700 backers and raised just short of $80,000 for further research. That’s not bad, but it’s still short of the $100,000 that the team needs just to rent lab space and buy basic equipment. It will take $500,000 to start producing new batches of DRACOs, and a million to start testing them on viruses in the herpes family. So yeah, there’s still a long way to go.

“We want this to go viral,” says Rider in the campaign video. It’s a great slogan, but it might be wishful thinking. Can the public at large really get excited about a discovery that is still at least four years away from reaching the point where a pharmaceutical company might pick it up and begin to fund the long process of clinical trials and FDA approval? Each application of the technology would need its own set of trials, each costing a small fortune, with no guarantee that a new drug will ever come to market. The hurdles that remain are enormous, and in that sense the public skepticism that this is all too good to be true might be warranted.