Revisiting 'La Jetée,' the 1962 Experimental Inspiration for '12 Monkeys'

Time, fate, paradoxes, and half a century of telling different sides to the same story.

Through two time-bending seasons, Syfy’s 12 Monkeys has broken free of the burden that haunted its January 2015 debut and maybe caused a few potential viewers to unfairly pass it over. Why does there need to be a 12 Monkeys TV series? Oddball auteur Terry Gilliam’s 1995 film of the same name was a complete story that didn’t need an expanded universe to elongate the movie’s 129-minute film into a multi-season storyline. Unfortunately, this line of reasoning misses the point of the story. Regardless of whether a time traveller going back to try and save the world from an apocalyptic catastrophe is told in two hours or 26 hours, a TV show about time travel can use an existing premise to tell an entirely new collection of stories. Surprisingly, the story can also be told in only 28 minutes.

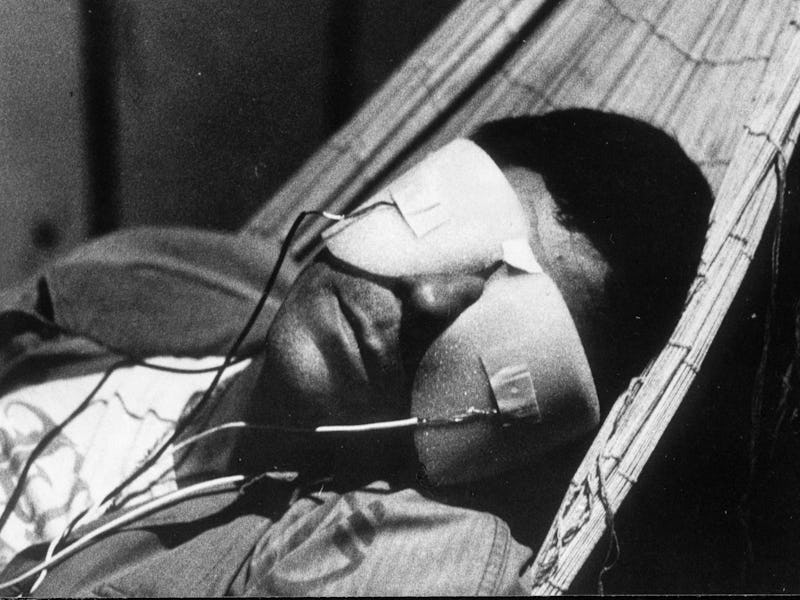

While the 12 Monkeys TV show is a specific reinterpretation of Gilliam’s film, with the “Based on the motion picture 12 Monkeys, screenplay by David Peoples and Janet Peoples” credit running before each episode, the show is technically also based on the 1962 short film (or “photo-roman,” a.k.a. photo story) that provided the inspiration for the narrative Peoples and Peoples set down in their screenplay. Enigmatic multimedia artist Chris Marker’s seminal short film La Jetée, which is told entirely in still photographs save for a single moving image over the course of just under 30 minutes, covers basically the same fundamental ground of the movie and TV series it inspired — and arguably does it better.

The survivors in La Jetée trade the post apocalyptic Philadelphia of the show and movie, brought about by the spread of a deadly plague, for a post-World War III near future in the Palais de Chaillot galleries underneath Paris. Scientists are researching time travel “to call past and future to the rescue of the present” by using expendable prisoners like the unnamed protagonist. Our man (Davos Hanich) is chosen to go back in hopes to prevent the war because he is “marked by an image from his childhood” before the bomb was dropped on Paris of an unnamed woman (played by Hélène Chatelain) he remembers seeing before witnessing a man die on a jetty at Orly Airport.

While in the past he meets the woman from his future-past and they fall in love, but he’s soon sent far into the future and given a “power unit” from the people there that can somehow reset the devastation of his apocalyptic past. To save himself from being executed in Paris once his mission is complete, he chooses to go back in time to be with the woman he fell in love with. Just as he meets her at Orly, one of the scientists from his post-apocalyptic present kills him, and he realizes the person he saw die as a child was his future self.

It would almost be too foolish to directly compare the 12 Monkeys TV series to Marker’s film because they’re so unbelievably different besides a few superficial-to-legitimate allusions. A line of La Jetée’s gorgeous narration that says, “Nothing sorts out memories from ordinary moments. Later on they do claim remembrance when they show their scars,” offers a nice thesis on all three. But there aren’t monkeys anywhere in La Jetée other than in a scene where the man and woman meet in a museum “filled with timeless animals.” Yes, travelers in both sit reclined in mysteries contraptions before suddenly finding themselves sent through time, a scene where the man and woman tour huge trees recalls the enigmatic red forest of the TV show, the show’s mad scientists Jones (Barbara Sukowa) wears similar goggled eyewear to the Parisian scientists from La Jetée, and a possibly dead character from the series is named “Marker” in honor of the short film’s director.

Other than that the show’s references stick more closely to Gilliam’s film. Cole, Railly, Goines, Jose, and Jones are characters in both (in the show’s most fascinating change, Railly’s name is changed to Cassandra to mirror the “Cassandra Complex,” referencing the greek goddess burdened with the foresight of future events). But besides the surface level, the execution of three generations of the same story couldn’t be more different.

Marker’s is an artist’s rumination on time, memory, and fate; Gilliam’s is his take on a Twilight Zone-esque sci-fi thriller; and the Syfy show is a time-obsessed cult mystery that expounds upon its own mythology with each brilliant episode. On top of that, time in Gilliam and Marker’s films is fatalistic. “There was no way to escape Time,” says La Jetée’s narrator. In the TV show, time is self-determined. “Time evolves,” a screed from the show’s mysterious puppetmaster known as The Witness says in a recent episode. They’re each unique, bizarre, and complicated — and that’s the point. Each could have been a different time loop of the same story. They’re all a paradox worth exploring.