Expert Says Hyperloop Is Wrong for Shipping: "Why Do We Need to Move Cargo at 500 mph?"

Faster isn't always better.

Hyperloop, the high speed, low-carbon, near-vacuum-sealed tube conceived by SpaceX and Tesla CEO Elon Musk, is starting to take shape. Though the futuristic travel solution has clear people-moving potential, its usefulness in the field of cargo transport is far murkier.

One of Hyperloop’s best and most talked about qualities is its speed. Hyperloop One, the company that successfully tested its propulsion system this week, aims to reach speeds as high as 750 mph. But, Barry Prentice, professor in supply chain management in the University of Manitoba’s I.H. Asper School of Business, says speed is of relatively little consequence to cargo transport.

“Why do we need to move cargo at 500 mph?” Prentice tells Inverse. “People are a different matter. People value their time, but cargo doesn’t. People who ship cargo value cost much more than time.”

He says there will certainly be a particular market for those who wish to ship cargo between L.A. and San Francisco in 30 minutes, a time-of-travel that Elon Musk has said will be possible with Hyperloop. For example, those sending perishable items may wish to take advantage of the speed, or consider a case where an organ needs to get from one city to another quickly for an emergency transplant. But, Prentice says Hyperloop will ultimately prove impractical and too expensive for most shipping companies.

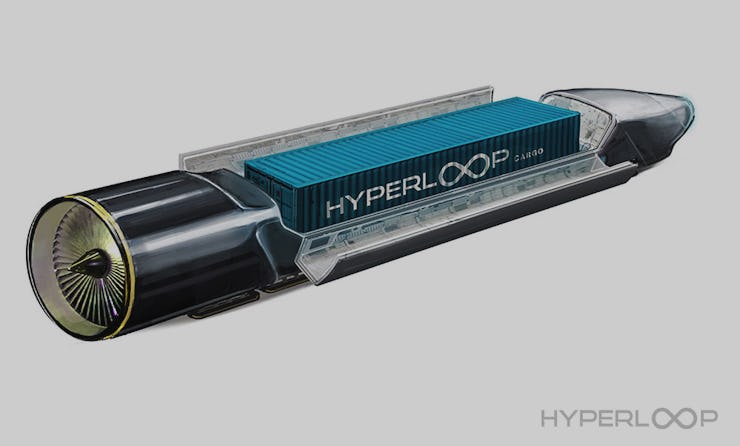

A concept illustration demonstrates how the pod would be loaded into the hyperloop tube.

When Elon Musk talks about low costs, he’s pointing to building the pod and making passenger trips inexpensive. In his 2013 open-sourced whitepaper, titled “Hyperloop Alpha,” he wrote about the cost efficiency of this carbon-neutral transport system. Solar panels lining the outside tubes would largely power the electronics, making individual trips as cheap as $20 per person. He also charted the predicted cost of building such a system and concluded that a passenger-only line would cost $6 billion, and a slightly larger passenger-plus-cargo line would cost $7.5 billion.

When shipping companies talk about low costs, they speak in terms of cost per volume shipped. And individual pods are not going to be able to ship much cargo per trip when compared to other, more established forms of cargo transport.

The whitepaper details that the cargo-outfitted hyperloop would need to increase to a 10-foot, 10-inch diameter to accommodate the extra needed space. That would make sense based on Hyperloop One’s concept drawing, which shows one standard eight-foot-tall, 20- or 40-foot long freight container being loaded into a pod.

Meanwhile, 18-wheeler semi trucks haul some 80,000 pounds of cargo in 70- to 80-foot long trailers; conventional rail trains, on average, pull more than 6,000 feet in length of those same trailers, and freight ships taking cargo across oceans can hold hundreds of them for bafflingly large-volume hauls.

Construction on a test hyperloop track begins.

It’s hard to imagine a hyperloop system competing with these modes of large-cargo transport, but it doesn’t seem like Musk’s initial concept means to compete on that level, anyhow.

His white paper lays out a plan for a passenger-plus-cargo line, so perhaps the plan is more focused on supplementing passenger travel rather than disrupting large volume competitors.

“Sure, if it’s all built and there’s only 50-percent utilization through passengers, might as well put some cargo on; it’s better than nothing,” Prentice says. “But I don’t see cargo ever carrying the full cost.”

Air ships such as the Airlander 10 would prove a much more disruptive technology in cargo transportation, and at the onset, maybe Hyperloop should stick to what it’s meant to be best at: passenger transport.