Classic Science Fiction Films Assumed Humanity Was An Established Presence In Space

Taking a look at older space exploration science fiction films and noting the differences between then and now.

Science-fiction cinema has grown in both popularity and scope since its initiation into the larger culture. We’ve now entering an age in which sci-fi films are categorized into subsections of tone, prescience, and aesthetic.

While there are plenty of science fictions films and television series that delve into alternate futures — post-apocalyptic scenarios, time-travel, dimension-hopping, etc — the category of science fiction that seems to be experiencing a change lately deals strictly with adventuring in outer space.

As the captain so memorably says in Star Trek, the mission of the Starship Enterprise is “to explore new worlds; to seek out new life, new civilizations; to boldly go where no one has gone before.” Throughout the entire series, the crew traverses the vastness of space to find all of those new things, but that’s because humans have settled into space comfortably enough that they feel confident in their place in society to go out and explore.

Many sci-fi movies and series of old focused more on worlds where human life was already an established presence in outer space. Humanity had made a home for itself on planets other than Earth. Now-dated science fiction told us of humans already living and thriving in space, developing governmental and social structures within a futuristic setting.

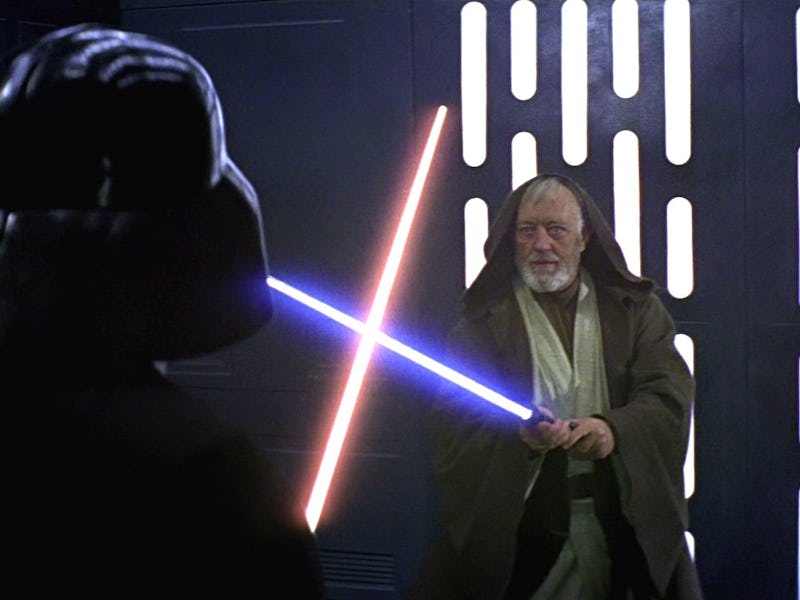

There was as much world-building in these futures as we currently see in the fantasy genre. Just take (yet another) look at Star Wars. That galaxy far, far away is divorced from our own solar system; it has completely new planets and species and cultures.

It’s fun, fantastical, and mythological. There’s even a karmic Force that holds the universe together, so it kind of teeters on the line between fantasy and science fiction; the approach to detail-oriented world-building between the genres feels similar. Universes and alternate realities and planets become complex and magnificent settings which frame the story and characters.

Within the designated setting there’s going to be a conflict, obviously, but the problem usually arises from a clash of man v. man, man v. society, or man v. self. Space travel is already a staple in the setting, so the friction has to happen beyond the development of new tech. The backdrop never defines the conflict; it merely uses it to accent the story’s characters and plot. Shows like Cowboy Bebop, which came out in 1998, use the futuristic setting to create a new world. The human presence on Mars or the space-traveling gates never encroach on the story, merely accentuate it.

Now, the trend in science fiction leans more towards man v. nature, instead of conflict from human intervention. While some of the most influential and iconic movies of the 80s and 90s are host to a number of terrifying monsters in the “nature” position, like the xenomorphs from Alien, the conflict comes from what is within space, not from outer space itself.

Interstellar, The Martian, and Gravity pit man against the ever-pressing danger of space exploration. Before, we’ve seen humans completely at ease in their future position in space, but lately the science fiction is more about the tenuous practicality of space travel, of actually entering space rather than already being in space.

This is probably due to the very real possibility of space colonization within sight. SpaceX’s Elon Musk hopes (and is pushing for) a multiplanetary presence in the near future, and more and more people are fully discussing the practical approaches in which we could travel to the stars and colonize.

We’re experiencing films which play with this possibility and are trying to show a possibly reluctant audience that option. We’re getting as accurate a depiction of space as we can in a fictionalized story on the big screen, so films are straying away from the totally bizarre and new, and are imparting a realistic what-if scenario about overcoming the inevitable.

Not only do filmmakers have to deliver that message and creative interpretation, newer science fiction — and this is a good thing — is becoming more accurate in its depiction of space and space travel. For Interstellar, Christopher Nolan approached Caltech physicists Kit Thorne to help with the creation of the black hole. It’s not as accurate as it could have been due to Nolan’s concern that audiences might find the gyrating and color-changes of a more precise illustration of a black hole confusing, but he definitely researched before following through.

Audiences, both academic and not, expect more realism in science fiction. We expect silence in space, no friction, and no gravity. This is to create a more lifelike and faithful depiction of places that we cannot go ourselves. This escapism into fictional worlds such as these allow for a more immersive viewing experience.

That wasn’t the main concern before. And it shouldn’t always be now. Older renditions of science fiction wanted to be immersive, too, but with a comletely different approach, As amazing as it is that we’re able to experience space through different storytelling mediums with a little bit more precision than previously, that eclectic mash of remarkable ideas that spawned diverse and wondrous worlds is missing. We’re only glancing out at the approach into space and ignoring the possibility that we actually make it and we’re spinning around in a Stanford Torus Space Settlement wreacking havoc there instead of on Earth.

Now, instead of teetering along the line of fantasy, because we’re missing that expansive world-building that contrasts from our own world, these newer additions are almost tethering the line on straight fiction, instead.