When It Comes to Tesla's Gigafactory, Nevada Officials Can't Keep a Poker Face

Expectations are sky high in Storey County, where progress has been unnervingly smooth.

The Tahoe-Reno Industrial Park sits just off Electric Avenue, about a mile away from where I-80 runs parallel to the Truckee River toward the “Biggest Little City in the World.” The closest notable structure is a PetSmart distribution center. Beyond that, there’s the Walmart distribution center and the Food Bank of Northern Nevada. This is the unlovely neighborhood where Elon Musk and Tesla have chosen to build one of the largest — and arguably most economically significant — buildings on Earth. This is the future site of the Tesla Motors Gigafactory.

Elon Musk and Tesla announced the Gigafactory in 2014. The monumental battery-production plant was always going to be in the United States, but Nevada had to woo the electric car manufacturer. The state efficiently managed that trick by offering a number of incentives and abatements worth an estimated $1.3 billion, a figure Fortune and The Verge decried as irresponsible. Amid the discussion, Tesla’s public relations core kept to the script, making a mantra of a simple truth: Relative to the $100-billion cost of the Gigafactory, which will take two decades to construct, the incentives offered were actually somewhat minor — and performance-based, at that. Tesla will have to support local education and infrastructure and employ 6,500 people, over half of which will be Nevadans, to hold up its end of the bargain.

The debate about the money proved ephemeral, presumably because Tesla’s flacks actually had a point and also because the concern was never really about the money. Nevada, like most states, wants as many people as possible to know about its business incentives. Ultimately, the money wasn’t an issue: scale was. What would happen to the people out there in the desert? Would a growing company smother small towns? That’s where Pat Whitten and Geno Martini come in. They are in charge of protecting Nevadans from a company that — evidence would suggest — intends to do right by them. They are watchmen, but they’re also rooting for Tesla: they want to see the Gigafactory’s promise realized.

Elon Musk.

Storey County is home to about 4,000 people, and its previous claim to fame, Whitten, the county manager, says, was Virginia City, “a little, quaint, Western town that, with gold and silver from the mines in the 1860s, financed the latter part of the Civil War for the Union side.”

Whitten is now a Tesla disciple. He joined his girlfriend on a trip to Rocklin, California, to wait in line and reserve a Model 3, and he’s immensely proud that the Gigafactory will be in his county. “We’ve gotten not just national but international attention,” he says. But he’s less excited about the ink than he is about the fact the ink is warranted. The factory will be a massive boon for the local economy — and its product, hyper-efficient batteries, will make Storey County a smaller, drier, latter-day Detroit. For Whitten, there are basically two elements to the Tesla conversation: Planning to make sure things go smoothly and sharing credit for the big win.

“From my seat, this is a great company to work with,” he says. “They employ the best. I’d be hard-pressed to come up with anything negative. There are challenges — this is a big, big project. But the lines of communication,” Whitten explains, “are wide open at all levels of their organization, be it their construction team or their administrative levels high-up. I’m not trying to sugarcoat this — I mean, it’s all way good from our perspective.”

The Gigafactory is a little over an hour's drive from Lake Tahoe.

But nothing is all good. Whitten acknowledges that there has been a slight increase in traffic incidents on Interstate 80. That’s the one problem so far, but Nevada and Tesla foresaw it: Tesla volunteered to pay for two firefighter-paramedics for three or four years to help handle it. It’s also going to throw in a new fire truck capable of helping should something go wrong at the Gigafactory. “We didn’t have a ladder truck tall enough to serve a building that high,” Whitten explains. “We found a screaming deal on a nice, used one — screaming being $750,000, refurbished — and Tesla’s buying it.”

Geno Martini, mayor of Sparks (pop. 90,000) is less effusive than Whitten, but generally in agreement. “In a project that’s that big, sometimes you miss something, or there are unintended consequences,” he says. “There are no guarantees when you sign these kind of deals.” The warning is little more than an asterisk hanging over his enthusiasm. Martini is particularly excited to be seeing new housing developments and new jobs. “We’ve already experienced a lot of growth in the multi-family area in our downtown,” he says. “We’ve been trying for 15 years to redevelop downtown, and, all of a sudden, we’ve got everybody wanting to build apartments down there.”

It’s the trickle-down effects that truly mark the Gigafactory as a Muskian endeavor. Technological developments lead to social ones. These developments can be broad — decreasing dependence on Middle Eastern oil reserves, for instance — or narrow — gentrifying a corner of Sparks. The critical ingredient isn’t capital, but swagger. (Capital, though, does help.) And Musk’s run-and-gun approach, Whitten says, is “vintage Storey County. They’re already in production in one part of the plant while they’re building another while they’re designing another,” he laughs. “That is what we do best.”

The Gigafactory is “intended to drive down the cost of energy storage,” a Tesla spokesperson tells Inverse. “The world could have built this capacity for us, but we saw an opportunity to drive significant cost savings into the products that we make, versus letting the world continue with the status quo.”

And this is a telling quote. The company sees itself as staying out in front. If it manages to do so, the market for its batteries will exceed the market for its cars — despite the roughly half-a-million Model 3 reservations. People are going to come to Storey County. Serious people are going to come.

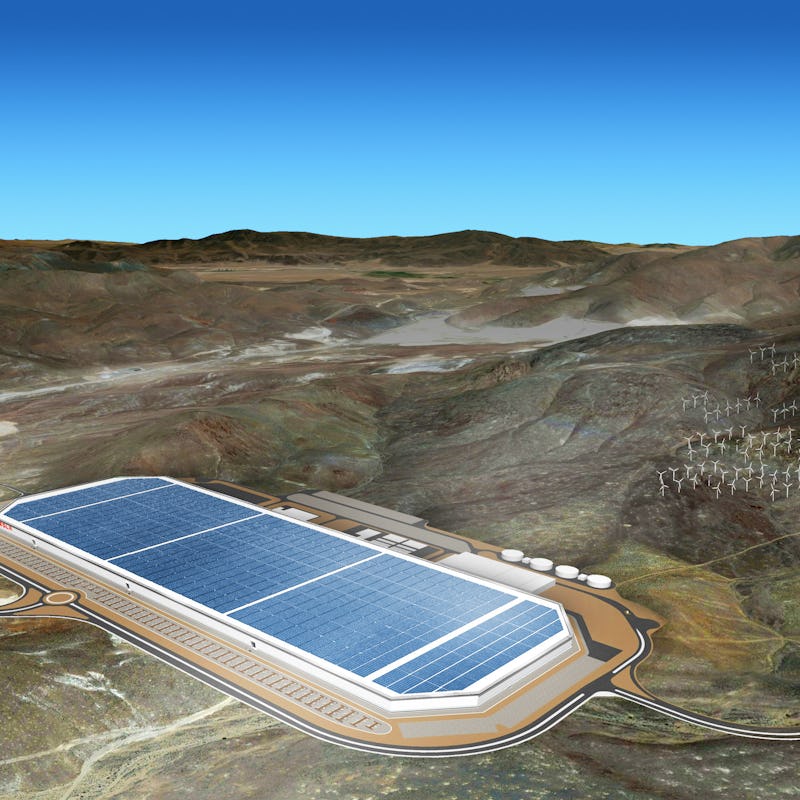

The nascent Gigafactory in March, 2016.

Storey County was gold country during the rush westward, but the Gigafactory doesn’t represent a mother lode. It may represent something better. There’s wisdom in that old adage about it being the people who sell shovels, not the miners, who get rich in a gold rush. What Tesla intends to build is the biggest shovel factory ever conceived. That’s good news for the descendants of people who panned the Truckee River.

Martini’s been over to the construction site several times, and he’s impressed. “It’s hard to envision something that big unless you actually see it,” he says. “I never thought we’d see anything in this region like that. I’m telling you: you actually have to go and physically look at it to comprehend how big it really is. You can’t put into perspective in your mind what five million square feet looks like.”

The construction site back in February, 2015.

And Whitten’s just thrilled to be along for the ride. The Gigafactory, he says, is “the most dynamic and exciting project I’ve ever been involved with.”

It’s big and great and, aside from a few car accidents, everything is moving ahead as intended. For now, all Pat Whitten and Geno Martini need to do is keep an eye on the Gigafactory as it grows and grows. They are rooting for Tesla — no doubt about it. They’ve been given no reason not to. But, still, they’re going to keep watching. Just in case.