NASA Confirms 1,284 Newly Discovered Exoplanets

And at least a few of them show some promise of potential habitability.

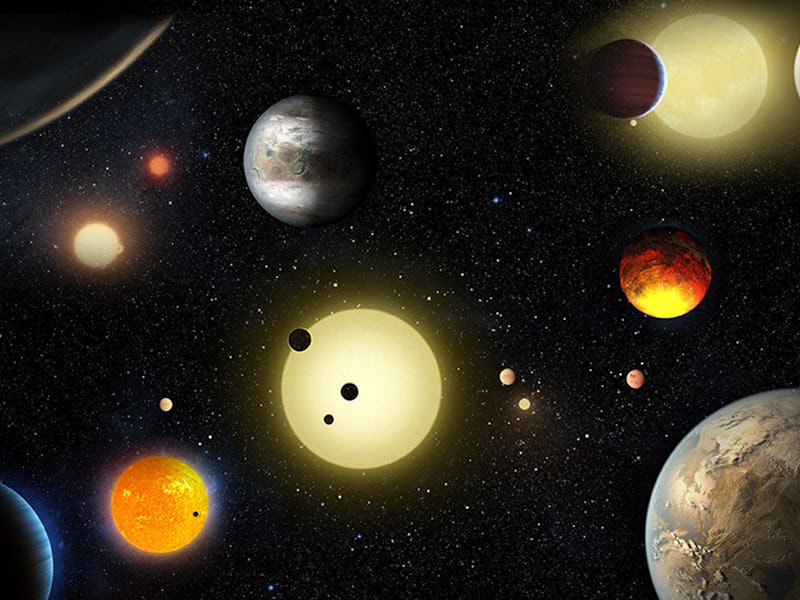

Before Tuesday, NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope had been used to officially identify just around a thousand exoplanets floating around the known universe. Since launching in 2009, Kepler has been an invaluable tool in helping illustrate the insane variety of worlds permeating the Milky Way galaxy.

In a bombshell announcement, NASA and a group of scientists working with Kepler have just announced the confirmation of 1,284 new exoplanets — more than doubling the previous number. It’s the single-largest exoplanet finding to date — a treasure trove of new data that’s a boon to those interested in finding other worlds that are potentially habitable.

More importantly, the new data is a crucial step forward in answering the question of whether we are alone in the universe. “We live in a time when humanity can answer this question scientifically,” Paul Hertz, astrophysics division director at NASA, told reporters on Tuesday.

The histogram shows the number of planet discoveries by year for more than the past two decades of the exoplanet search. The blue bar shows previous non-Kepler planet discoveries, the light blue bar shows previous Kepler planet discoveries, the orange bar displays the 1,284 new validated planets.

These new findings are thanks to a new kind of validation method — developed by Timothy Morton, an astronomer based at Princeton University — that uses a new technique to automatically assign a probability that an exoplanet candidate is really a planet, based on new statistical computation. Previous techniques hampered exoplanet research because of the time and resources required to confirm a planet or deduce it as a false positive, involving radio velocity observation, high-resolution imaging, and other tests.

A Whole Bag of Bread Crumbs

Planet candidates can be thought of like bread crumbs,” said Morton. “If you drop a few large crumbs on the floor, you can pick them up one by one. But, if you spill a whole bag of tiny crumbs, you’re going to need a broom. This statistical analysis is our broom.”

The result is about 550 rocky planets that have a similar size to Earth. Nine of these are located in their star’s habitable zones (affectionately referred to sometimes as the Goldilocks zone) where things are just right: surface temperatures are most likely to allow for liquid water to exist on the surface, for one. Those nine exoplanets join 21 others that make up the Goldilocks planets.

“They say not to count our chickens before they’re hatched, but Tim’s numbers allow us to do exactly that,” Natalie Batalha, a Kepler mission scientist, told reporters. She’s referring to the fact that Morton’s technique makes it much easier to determine whether candidate objects — the eggs — will “hatch” into bonafide, confirmed exoplanets.

Astronomers find exoplanets by using Kepler, and sometimes other instruments, to look for objects that transit in front of stars and cause the starlight to dim slightly. Follow-up analysis is used to determine whether those objects are indeed plants, or whether they are actually false positives caused by “imposters” — which are often times smaller stars masquerading as planets.

Kepler's candidates require verification to determine if they are actual planets and not another object, such as a small star, mimicking a planet.

All the planets confirmed today were initially observed during the first Kepler mission, which looked at about 150,000 stars over the course of four years. The Kepler Space Telescope itself is currently in the midst of the follow-up K2 mission.

“Before the Kepler space telescope launched, we did not know whether exoplanets were rare or common in the galaxy,” said Herz. “Thanks to Kepler and the research community, we now know there could be more planets than stars.”

The next steps require putting more time toward studying the Goldilocks planets more in-depth. The two most important resources to this goal are the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, which will be tasked with surveying nearly the entire sky and looking at more stellar transits across 200,000 other stars; and the James Webb Space Telescope, which will be capable of tracking specific star systems and exoplanets and measuring the filtered starlight to observe the atmospheric composition of exoplanets.

The latter is crucial since the ultimate goal in studying exoplanets — especially the Goldilocks ones — is to find out whether they contain biosignature gases that are indicative of life on the surface.

The orange spheres represent the nine newly validated planets announcement on May 10, 2016. The blue disks represent the 12 previous known planets. These planets are plotted relative to the temperature of their star and with respect to the amount of energy received from their star in their orbit in Earth units.

As summed up by Charlie Sobeck, the Kepler and K2 mission manager at Ames, these endeavors are just the latest in “an arc of discovery aimed at answering the question of alien life.” The Kepler Space Telescope is already showing signs of slowing down, and these latest findings are an encouraging sign that we’ll be able to harness newer technology more effectively when it comes to future exoplanet research.