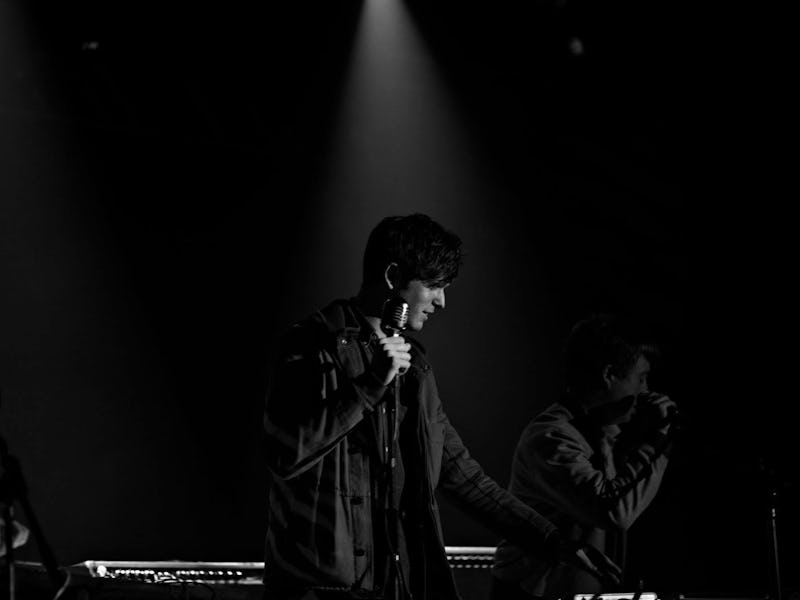

James Blake's Latest Album is a New Musical Blueprint

And his eminently listenable new album isn't afraid to flaunt how listenable it is.

As London singer/songwriter/producer James Blake has grown in popularity — fraternizing with everyone from Chance the Rapper, to Kanye, to, now, becoming Beyoncé’s most trusted collaborator — his music has begun to seem more and more anodyne. But that’s probably not his fault: The downtempo glitch’n’B he earned his stripes with has simply become a dominant part of both the indie (How to Dress Well to Shlohmo) and even pop (Channel Orange to Tinashe) landscapes since he first emerged in 2010. He’s the veritable Andrew Lloyd Weber of “bedroom R&B”: first, a pioneering figure for a certain strain of music, and later, the smoothed-out expert whose albums all occupy the same basic niche.

Some might say: Why listen to James Blake these days when you could listen to equally moody, more experimental R&B artists — say, FKA Twigs, Dawn “DAWN” Richard, KING? Of course, listening to Hall & Oates’ pop amalgams never meant one couldn’t listen to undiluted Philly soul, or edgier new-wave, for that matter, though maybe some things were cooler than others.

James Blake doesn’t have the infectious songs that made Daryl and John a fact of life in the ‘80s, but he does have an equally timely and ubiquitous sound. What started as a uniquely chilly, future-shock R&B sound — mixed with dubstep bumps in the night borrowed from Burial records — eventually became a control variable in musical culture. Today, Blake-like music and even mood instrumentals have started to dominate the coffee shops, restaurants, and clothing stores of urban America.

His new album The Colour in Anything spits every trait of Blake-y music you might be sipping a cortado to right now back out in crystalline form, across its daunting 76 minutes. The sound is deadly chic as much as personal, and utilitarian in its unassuming consistency from song to song. It will touch nerves for people who enjoy the singer/songwriter’s later smooth, melismatic balladry, and those who crave more atmospheric constructions (“f.o.r.e.v.e.r.,” “The Colour in Anything”) in which Blake weaves his pitch-shifted and heavily overdubbed voice into throbbing, interlocking tapestries (“Timeless”).

Some of the best songs involve a combination of Blake’s two primary approaches. He’ll tweak a piece that could be an ear-catching chart hit into an appealing, poignant album cut. The main example here, of course, is the Bon Iver collaboration and album highlight (“I Need a Forest Fire”). Songs like this helps one recall what makes James Blake remarkable in himself, and his albums more than just a catalogue of now-very-trendy production gestures. The backdrops of glitchier numbers (“Two Men Down”) — punctuated by anomalous samples — recall the more unprecedented sound of his earlier, largely instrumental EPs, 2010’s CMYK and Klavierwerke.

But most of all, The Colour in Anything seems content with being something we fade pleasantly in and out of. It’s music for use and getting work done to, but also rewards attentiveness and promotes meditative abstraction. Chock it up to a New Tedium — the alt equivalent of ZAYN’s recent lengthy, same-y new album. Or call it Blake being Blake: a surprisingly successful artists doing a victory lap in balletic, Chariots of Fire slo-mo. He’s honed in on his brand: so in-demand now, a useful tool for pop artists and a standard for indie artists dabbling in MIDI drums, samples, and Sade albums. If you’ve got a product that’s so in-demand, why bend it out of shape?