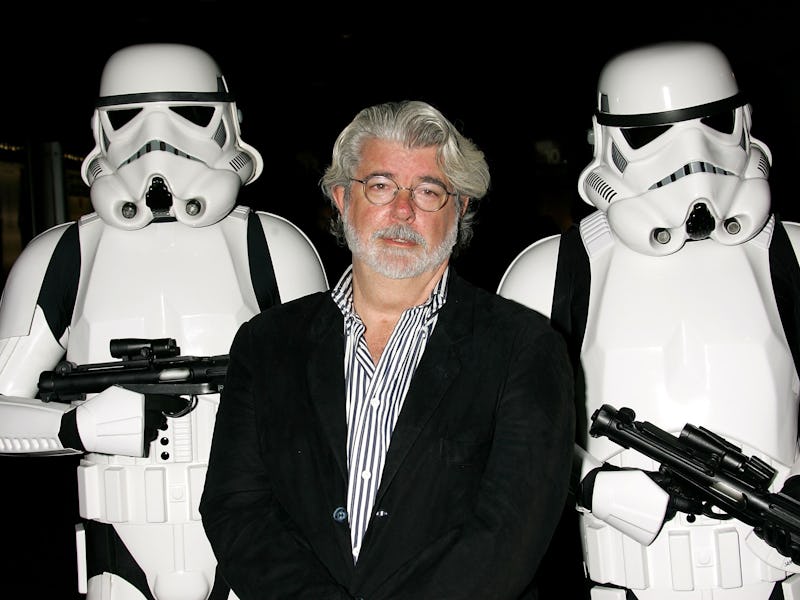

7 Excellent Changes George Lucas Made to the 'Star Wars' Saga

Not everything in the Special Editions was great, but some of it was.

It seems like a galaxy-sized amount of space has been devoted to trashing former Star Wars mastermind George Lucas’ tweaks and changes to the saga. And some of the changes made over the years are indefensible, including Han shooting first, that horrendous CGI Jabba the Hutt, unnecessary additions to the inhabitants of Mos Eisley, and Vader’s bellowing “nooooo!”

So with all the aggressive criticism of Lucas’ retouching, it can be difficult to cut through the din of the hateration and take a step back and realize that some of Lucas’ tinkering actually made elements of the Star Wars movies better. But it’s true! So take a deep breath, feel the Force flowing through you, and let us tell you some examples of George Lucas’ changes that were actually beneficial to the series.

7. Biggs Darklighter

Perhaps one of the more glossed over details about A New Hope, the film that started it all, is just why Luke would be reluctant to leave Tatooine. It’s a desolate, godawful rock of a planet where the only joy Luke ever experienced came from hanging out with his unseen friends at the Tosche Station and chatting with droids. To add some logic and dramatic weight, Lucas added in extra scenes with Luke’s childhood friend Biggs at the end of A New Hope, putting him in an X-Wing during the Death Star run. (Earlier scenes showing the pair hanging out with a group of friends remain deleted.) While Biggs is seen in the theatrical release, he’s barely around, and adding in a few more beats makes his death during the end battle have much more dramatic weight.

6. The Praxis Effect

The original special effects on Star Wars were cutting edge for their time. Some of them hold up to this day, but some didn’t age all that well. Case in point: the first version of the epic destruction of the Empire’s ultimate weapon in the original version just seems like a big fireworks display today. To make the destruction of the Death Star seem a bit more monumental, Lucas added something called the Praxis effect to the final explosion of the Empire’s enormous battle station. Just adding a rippling ring of explosive energy really drives home the idea that there was immense power that was just let loose from the Death Star to cap off the ending of the movie. The effects can also be seen when the Empire uses the firepower of their station to destroy Alderaan, and was added to the end of Return of the Jedi when the second Death Star explodes.

5. The end celebration

Turns out that showing all the known galaxy celebrating the defeat of the Galactic Empire is a way more effective way to end a movie than just showing a bunch of Ewoks dancing around their treehouses on Endor. Lucas adding views of the celebrations of the defeat of the Empire on Bespin, Tatooine, Coruscant, and Naboo at the end of Return of the Jedi may seem like an easy excuse to add looks at settings from the prequels, but it also quickly highlights the emotional release of what the Rebels were able to accomplish. The bad guys are gone, and now everybody can party — at least until The Force Awakens happens.

4. The Battle of Hoth

ILM continues to push the boundaries of what’s possible in special effects, and it’s a lot more streamlined and scientific than back in the late 1970s and early 1980s, when the company still had a DIY approach. Nowhere was this more obvious than when audiences watched snowspeeders jetting around Imperial walkers in the Battle of Hoth that opened The Empire Strikes Back. The blue screen process used on the first film allowed the special effects that composited the backgrounds and the spaceships could be hidden using the blackness of space, but it became a big problem against the white snow of Hoth. Digitally erasing some translucent special effects lines made it easier to sell the illusion of the gritty battle between the surprised Rebels and the mighty Empire.

3. Cloud City

Lando Calrissian’s Bespin paradise was supposed to be a gorgeous and picturesque utopia among the clouds. But when audiences saw The Empire Strikes Back in 1980, it just seemed like Lando, Han, Leia, and Chewie were running around a bunch of plastic interior sets. Lucas wisely remedied the contradictory claustrophobia by adding CG shots of the city’s skyline as the Millennium Falcon makes its approach, and digitally removing some of the walled off panels of the interiors to make them into windows, which showed off the city’s auburn-hued beauty. It sells the idea that the place is an ideal escape, and better sets the audience up to be deceived when Lando sells his friends out to Darth Vader and Boba Fett.

2. Ian McDiarmid as Emperor Palpatine

When the then-mysterious Emperor first appeared onscreen in The Empire Strikes Back in 1980, his decrepit greyish visage wasn’t the Palpatine we all know today. Actor Ian McDiarmid was cast as the evil hooded figure for Return of the Jedi and would eventually revisit the character as the younger puppet master pulling all the strings in Lucas’ prequels. In a bit of effects trickery, the hologram cameo of the Emperor was originally played by makeup effects artist Rick Baker’s wife Elaine, and actually had a chimpanzee’s eyes superimposed over her own to make the character even more sinister. It’s perhaps the most sensible example of George Lucas’ voracious appetite for continuity throughout his space opera.

1. The Battle of Yavin

Star Wars is well known for the artistry of its practical effects, including enormous and detailed miniature models of ships such as the Millennium Falcon and Vader’s Star Destroyer. But Lucas wisely updated the ships in certain shots with digital versions to up the wow factor years later. The CGI Falcon blasting its way out of Mos Eisley was a marked improvement, but the real scenes where Lucas’ digital switcheroo works best is during the Battle of Yavin. The CG X-Wing squadrons and more dynamic shots of the battle against the Death Star were necessary in making it digestible for a contemporary audience without losing any nostalgia for the scene itself.