How Chile's Unique TRAPPIST Telescope Found Habitable Planets 40 Light-Years Away

TRAPPIST was supposed to be just a prototype, but turned out to be the little-telescope-that-could.

Astronomers have just found our best chance of finding alien life to date in the form of a trio of potentially habitable planets only 40 light-years from Earth. The discovery comes thanks to a specially designed telescope in Chile called TRAPPIST (Transiting Planets and Planetesimals Small Telescope). It’s a remarkable piece of equipment.

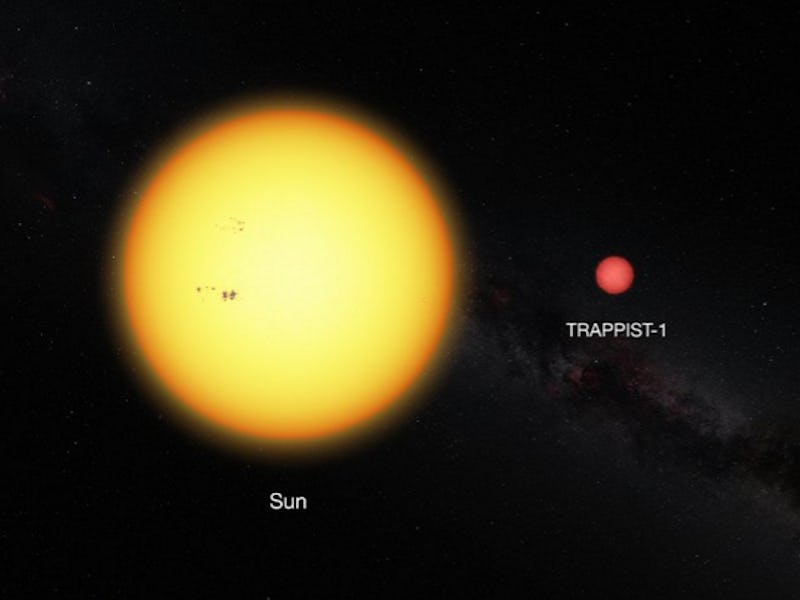

TRAPPIST, a robot telescope used specifically for targeting ultra-cool dwarf stars, was installed in Chile in 2010 and has been active since 2011. Unlike bigger, brighter stars, ultra-cool dwarf stars require more specialized telescopes to study them. TRAPPIST is one such telescope, and the discovery of these three planets is the first time the study of ultra-cool dwarf stars has yielded results. The star was named TRAPPIST-1 in its honor.

The discovery itself was almost an accident: TRAPPIST’s purpose was to serve as a prototype for the more ambitious project SPECULOOS (a Search for Planets Eclipsing Ultracool Stars), an upcoming endeavor to explore all visible ultracool dwarf stars which are bright and near enough to be worth studying. SPECULOOS will require bigger telescopes in better locations (cleaner light, better transparency of sky). But first, the methods had to be tested in Chile.

“This was only a prototype project, with only 60 stars being tracked, just to see if it could be done,” Michael Gillon, a principal investigator on the TRAPPIST telescope and one of the co-authors of the Nature article announcing the planets’ discovery, tells Inverse by phone. “We didn’t really intend to detect any planet. But it was crucial to have this telescope installed in a slightly worse location to just demonstrate that we could detect planets with it, but we ended up doing this in the best possible way, by actually detecting planets. So now everyone is convinced.”

SPECULOOS itself will involve a series of bigger telescopes than TRAPPIST, including one just installed in Morocco this week and, depending on how much funding comes through, one or two similar instruments in North America (likely Arizona or Mexico). Their missions will be the comprehensive exploration and survey of ultra-cool dwarfs in order to build the largest possible catalogue of Earth-like planets.

An artist's rendering of TRAPPIST-1 from one of the potentially habitable planets.

As for TRAPPIST, now that it’s already wildly outperformed everyone’s expectations, it’ll transition from searching for potentially habitable planets to focusing on the class of exoplanets called “Hot Jupiters” — giant planets with very short orbits, meaning they’re close to their respective stars — as well as comets.

“We want to study Hot Jupiters because they’re very stable to do detailed studies on,” Gillon says. “They tell us something about the way a planet forms and the evolution of the planetary system — these are formed very far from the star and then they get closer, and we have to understand why, to try to understand the nature of planetary systems not just by looking at our own solar system but looking on a galactic scale. And comets are the building blocks of planets — there are billions and billions of comets and asteroids that collided and formed bigger and bigger planets, so comets are remnants of this primordial phase and they can tell us a lot about the way that planets are formed.”

SPECULOOS telescopes are being tested through the end of the year. The project should begin in January 2017. “We want to start detecting these planets just as soon as possible,” Gillon says.