ALTERNATE FUTURES | Gernsback and the Brief, Bizarre History of Weather Modification

Hugo Gernsback predicted we'd be able to create rain and modify weather. Was it a literal case of "old man yells at cloud"?

“Twenty years hence, weather control will no longer be a theory. While it may take longer than this to actually have universal weather control, within twenty years it will be possible to at least cause rain, when required over cities and farm lands, by electrical means. But we shall not solve the problem of warding off or creating cold and heat in the open for many centuries.” — Hugo Gernsback, 1927

In 1927, Hugo Gernsback penned a series of predictions called “Twenty Years Hence” for Science and Innovation in which he sought to imagine what the world might look like 1947. Here, he imagines that by 1947, we’d be able to cause rain when we needed it — using electricity. In some ways, he was very close to being correct. In others, however, he was pretty wide of the mark.

Weather is a tricky business. There’s a reason why weather often comes up in discussion of chaos theory: Because its a system that has a “high degree of sensitivity to initial conditions and to the way in which they are set in motion.” It was meteorologist Edward Lorenz who first put forth the idea of chaos theory, in terms of the butterfly effect, in a paper called “Predictability: Does the flap of a butterfly’s wings in Brazil set of a tornado in Texas?” The idea was that something small like a butterfly flapping its wings could effect a change in condition and, as a result, the trajectory of a chaotic system like weather.

The weather depends on entirely on constantly changing conditions, making it deeply chaotic and complex. We do have methods for weather modification, cloud seeding being chief among them, but make no mistake: we don’t have control over the weather. There are ways in which we can change it, both intentionally and inadvertently, but we don’t have the ability to conjure or dispel storms at will. That said, let’s take a look at what we call “weather modification.”

The History of Cloud Seeding

The cloud seeding origin story dates back to 1946 in a General Electric lab with Vincent Schaefer and Irving Langmuir, who were studying particle filtration, precipitation static, and the problem of deicing planes. Much of their research took place in harsh conditions, but Schaefer needed a way to create the supercooled cloud conditions inside of the lab. So, he created a “cold box,” which replicated the conditions for study when he breathed into it to create small clouds.

However, according to the account from New Mexico Tech, in July of 1946 someone turned off Schaefer’s cold box. Needing it to do work, he procured some dry ice in order to cool it down post-haste. Curiously enough, though, the dry ice caused an unexpected reaction in the form of ice crystals in the box’s foggy cloud-like substance. Somehow, Schaefer had seeded a cloud quite by accident, using dry ice to create particles capable of producing precipitation. Later that year, they’d take it out of the lab and into the real world. From New Mexico Tech:

On November 13, Schaefer and pilot Curtis Talbot successfully used dry ice to induce precipitation in a cloud — “an unsuspecting cloud over the Adirondacks,” as Schaefer put it in a technical report. Having caught the four-mile-long cloud unawares, he and Talbot proceeded to plow a trough along its top with particles of dry ice. Snow began to fall from the cloudbase. Although the snow melted and evaporated before it hit the ground, the results were dramatic enough to change cloud seeding from a laboratory curiosity into a practical technique.

Cloud seeding is the method of using chemical substances like silver iodide or dry ice to affect a cloud’s ability to produce precipitation. Namely, it gives clouds a little boost in creating big particles that lead to rain and snow. Cloud seeding comes in two main varieties: warm and cold. Cold has to do with the formation of ice crystals and is the most common type of cloud seeding, while warm cloud seeding is a liquid process.

While it is used today in order to supplement precipitation in places like the Sierra Nevadas in California, it’s not a way to “make it rain,” if you will. Instead, it’s a way to increase precipitation in areas that already get rain and snowfall. After all, if we could simply create rain using cloud seeding, California wouldn’t be suffering under the weight of a crippling drought.

Weaponizing Weather and Storm Prevention

Cloud seeding isn’t the beginning and end of the weather modification story, though. Weaponizing weather is a big part of the weather modification narrative, and a big part of that comes from the Vietnam War, where the United States used cloud seeding to increase precipitation with the intention of deteriorating the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

As recently as 1996, the United States Air Force drew up a research paper outlining theoretical methods and purposes for weather modification as a military tactic. The plan discusses the use of rainfall to decrease comfort, morale, and conditions for enemy troops but also the possibility of using weather modification to create advantages with better conditions when appropriate. Among the most notable of the proposed methods is nanotechnology, which isn’t so much proposed here as it is dreamt about. In fact, the paper references “advances” over the next 30 years several times, largely counting on technology and progress to develop the means behind the weather modification notions put forth.

Though the idea of the military controlling the weather to sway conditions to their favor in conflict is disquieting, to say the least, it’s worth noting that the Convention on the Prohibition of Military or Any Other Hostile Use of Environmental Modification Techniques was signed and entered into force nearly forty years ago, swiftly prohibiting the use of weather modification as a weapon. Specifically, the treaty reads:

Each State Party to this Convention undertakes not to engage in military or any other hostile use of environmental modification techniques having widespread, long-lasting or severe effects as the means of destruction, damage or injury to any other State Party.

Of course, the applications for weather modification extend beyond weaponization. Much of the energy behind weather modification is aimed at preventing and mitigating storms.

Hail cannons, 1901, France

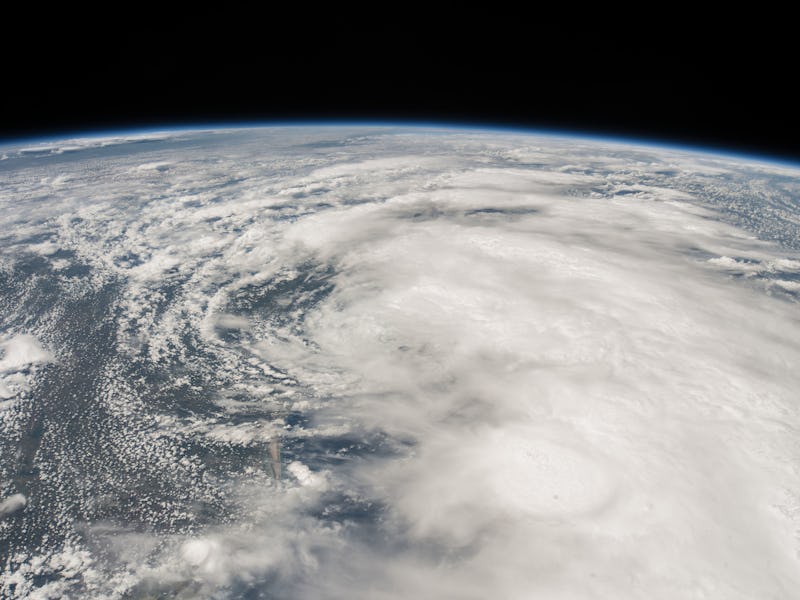

From hail cannons to Dyn-O-Gel to using big war machines to shoot chemicals at clouds, a number of methods have been attempted to contend with Mother Nature, but thus far they’ve been met with limited success. It’s difficult to prove or disprove the effectiveness of hail cannons due to the unpredictable and inconsistent nature of storms, and while Dyn-O-Gel is a theoretically sound method for crippling the power of hurricanes, the amount of the substance required makes it largely unfeasible. And while China’s attempts to hold off rainfall during the 2008 Olympics with rockets and chemicals may have been effective — again, weather’s an unpredictable thing; it could’ve also been luck — it’s difficult to see the practical, predictable, and widespread application of such methods.

Though we certainly don’t control weather and we can’t conjure rain when we need it like Gernsback thought we’d be able to, he was remarkably close on timeline. It was 1946 when cloud seeding went from theory to application, a year before Gernsback predicted we’d have such a technology. The event itself in GE’s lab was the result of pure happenstance, but nevertheless, Gernsback got damn close.

He was simply wrong in scope and method. We can’t “cause rain” over crops and cities when we need it. We can only supplement and increase rainfall, and that’s only if the cloud seeding method works perfectly, which isn’t always the case. Beyond that, Gernsback’s theoretical method was off. The means by which we manipulate weather to the extent we’re able to is chemical, not electrical.

It’s no real surprise that Gernsback went electric, though — in fact, many of his predictions are based on electricity. That’s because the ‘20s were an exciting time for electricity. The Industrial Age was energized by better motors, better wiring, and better distribution of electricity. It was a time of incredible growth, advancement, and progress in the electrical industry. Everything was going electric, so of course that’s where Gernsback thought weather modification would come from.

In the end, we don’t have quite the control over weather that Gernsback thought we would. Maybe with more advanced nanotechnology — or with some mystery substance like Dyn-O-Gel that isn’t hideously impractical to use — that wouldn’t be the case. Maybe in an alternate future.