The Success of the New York State Primary Depends on Old Voting Machines

With the New York state primary underway, registered voters have to put their faith in unreliable and aged machines.

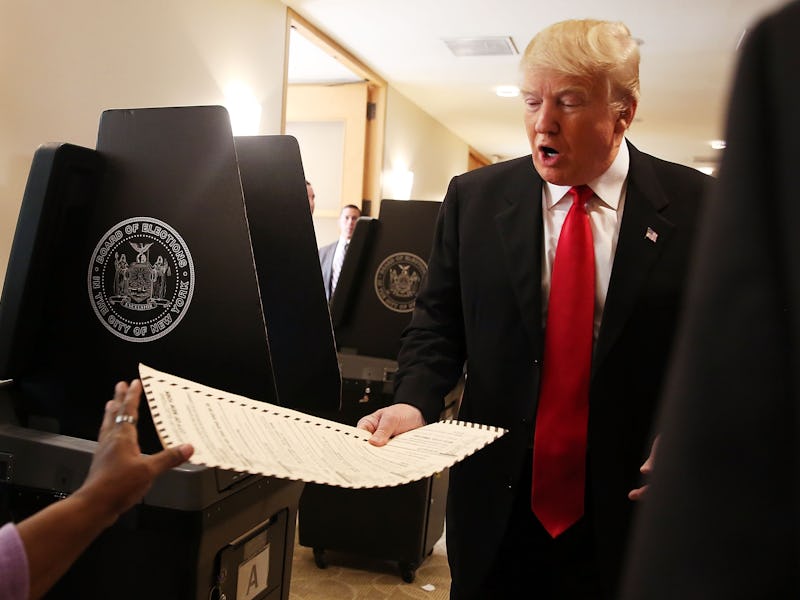

Today, six million registered voters across New York state are expected to head to the polls and vote in the closed primary election. It’s one of the biggest primaries in recent history: New Yorkers Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump have already cast their votes — Trump from a polling site in midtown Manhattan, and Clinton from suburban Westchester County. And Brooklyn native and Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders is running against Clinton, of course. Already criticized for being open only to registered Democrats and Republicans, this primary election is at risk for being slowed by another factor: Old voting machines.

As of Tuesday afternoon, voting machines had already disrupted the voting process in different parts of New York City. The New York Daily News reports that machines were broken at the PS 52 polling site in Queens while the Atlantic Terminal site, once it opened at 7:30 a.m., had no machines at all.

Five different machines across New York are used to count ballots. In New York City, most polling places use a DS200 Ballot Scanner system — a portable electronic voting system that uses an optical scanner to read marked paper ballots and then tally the results. People with a visual disability can use an ES&S AutoMark system, and the rare polling site will have the technologically-ancient Shoup Lever Machine. But for the most part, if you live in New York City, the DS200 — with its 31-step set-up process, like a politicized Ikea contraption — is what you’ll encounter.

“It eats them [the ballots] right up, I love them,” poll site supervisor Anna Barone told Inverse on Tuesday morning. Barone’s based in St. Francis Church Hall in East Williamsburg, Brooklyn. But Barone also says that with the increased reliance on the DS200, less elderly voters seem to be coming to the polls.

“A lot of the old timers just loved the levers, and I noted that so far a lot of them haven’t come out today,” she says.

Outside the St. Francis Church polling site.

In 2010 the Board of Elections in the City of New York, after input from public meetings, voted to phase out the lever system and utilize DS200 and AutoMark systems. But while electronic systems like the DS200 are seemingly more advanced, the machines are not without problems. Besides deterring elderly and low-income voters, the machines — which run on tens of thousands of lines of software code — are startlingly unregulated and unstudied.

In a 2015 report, the Brennan Center for Justice writes that there is no central location where election officials can learn whether the voting machines they are receiving have any problems. Election officials are completely reliant upon the public vendors distributing the machines when it comes to learning whether there are any malfunctions, defects, or vulnerabilities. As of 2015, 43 states were using machines that were at least 10 years old — a big issue when the machines, many of which were designed and engineered in the 1990s, are only expected to last 10 to 20 years.

But poll site officials aren’t informed how old the machines are. Barone said that Tuesday’s election was running smoothly so far — but she didn’t know how old the machines were or if they had been evaluated for functionality.

Hillary Clinton and former president Bill Clinton vote on Tuesday in the New York primary election.

The effort to revise this system is, at best, minimal. This is largely a factor of cash — it would cost an estimated $1 billion to upgrade the voting systems that the New York Times expects to “fail, crash, or produce unreliable results.”

But if the federal government were to step up and improve the system, the question begs: What should it change it too? Does the country need new machines, or a new system all together?

“Online would be better of course, because more people would participate,” said first time voter and Turkish immigrant Firat Parlak, to Inverse outside the Williamsburg polling site at PS 17. “But overall, the process that we have now is simple enough.”

Julie, who didn’t give her last name and voted at the St. Francis Church Hall location, said that she would prefer online voting as well — the machines weren’t necessarily a hassle to her, but they were also confusing enough that she could understand how they could be a detriment to older voters.

Denise Jones, who also voted at PS 17, didn’t even get to use a voting machine — the site had misplaced her registration, meaning her vote had to be counted as a paper ballot.

“The process wasn’t as efficient as I hoped it would be — but when it comes down to it, I’d always rather vote than not,” says Jones to Inverse.

“Online would be OK but I would prefer to be physically here — it feels more legit.”