The Pine Barrens Episode Marks 'The Sopranos''s Enduring Legacy, 15 Years Later

Christopher Moltisanti and Paulie Walnuts's night lost in the woods is still one of the HBO's drama's most iconic sequences

It’s hard to trace the lineage of influence in television, especially at the current cultural moment, when the amount of original programming has fanned out to accommodate so many more shows, each classifiable into new micro-genres that didn’t exist just a few years ago. These range from Louie-like dramadies to Mad Men-esque period pieces, from Twin Peaks-y cult homages to Game of Thrones-style costume dramas and Girls-ean comedies about dysfunction. There is simply too much TV to avoid comparisons, and yet there is also so much TV that there are too many comparisons to make — so few of them feel meaningful. Thus, nothing really seems to matter anymore amid the over-saturation, definitely not any particular show. Our favorite one ends, we flick through Hulu, half-hearted and at a loss for a way out of the routine.

But it is fairly easy to find the roots of today’s prestige TV drama in the defining years of ‘90s-era HBO original programming. Showrunners used the freedom of the premium-cable format to extend the possibilities of what a television show could be — to explore different ways to achieve a powerful cumulative result, without being as beholden to formulaic structures and restrictive runtimes. On shows like Oz and The Wire, the regimented format of individual episodes was broken down.

Few shows — if any — have left a greater imprint on the style and character tropes of today’s “serious” serial dramas than the David Chase-created HBO series The Sopranos. Today, the breed of sometimes-sympathetic, sometimes-despicable, and always haunted anti-hero and flawed family man that James Gandolfini made the most compelling character type on television is omnipresent. The lineage extends through Don Draper, Vinyl’s Richie Finestra, Billions’ Bobby Axelrod, Empire’s Lucious Lyon, and even closer ancestors like Deadwood’s Al Swearengen.

From the shots of Gandolfini, dead-eyed in his bathrobe, staring bemusedly at the ducks in his swimming pool in the show’s pilot, the 1997 viewer of The Sopranos knew that this would not only be no normal gangster drama; it would be no normal television show. What did these ducks mean? What was wrong with this guy, exactly? There weren’t clear answers to those questions — at least that we (or Dr. Jennifer Melfi, for that matter) would come to grips with anytime soon.

Creator David Chase — heavily involved in the show until the very end of its run — hoped to tell his unusual story using a more cinematic approach. A diehard movie buff, there was only a narrow swatch of television he cared about, and had no regard for how it was usually done.

So Sopranos episodes began to detour off into more eccentric and self-contained plotlines — from Tony’s dream of a beautiful next-door neighbor when sick with food poisoning in Season 1, to Tony lost in a coma as salesman alterego Kevin Finnerty at the beginning of Season 6.

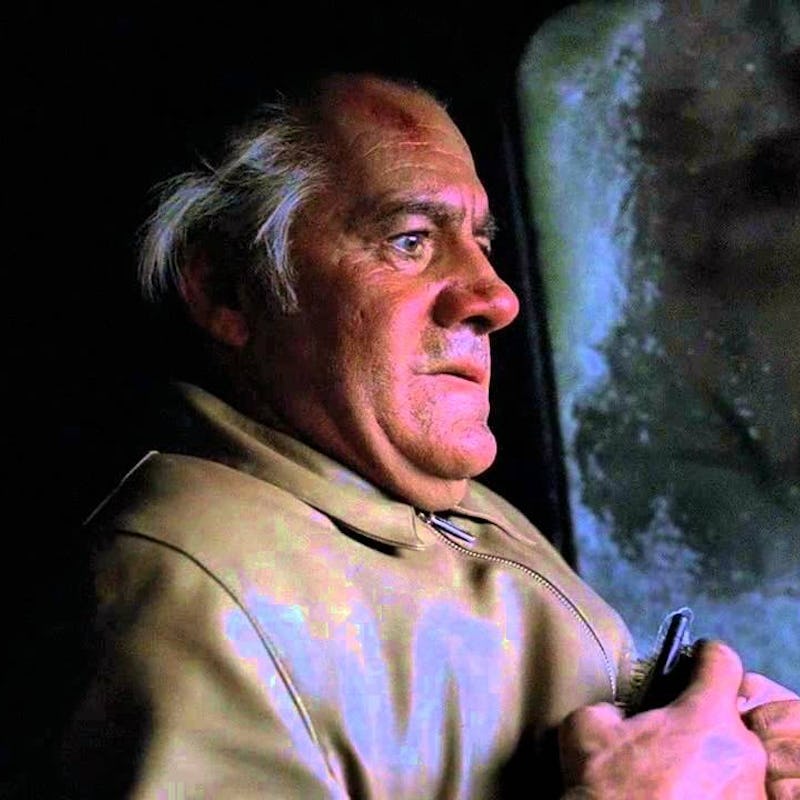

Perhaps no Sopranos diversion is as iconic as Christopher and Paulie’s apropos-of-nothing woodland adventure in Season 3’s “Pine Barrens.” Directed by Steve Buscemi, who would join the cast as Tony Blundetto, Tony’s just-sprung cousin, in the 5th season — the episode starts out unassumingly enough, with Tony’s relationship with his latest mistress Gloria Trillo (Annabella Sciorra) imploding on his boat. Tony then sends Christopher and Paulie (Tony Sirico) to collect money from a Russian mob member named Valery at his home.

From there, the episode turns toward textbook pitch-black Sopranos humor: Paulie flies off the rails over a minor insult (see the following season’s “Eloise” for the ultimate culmination of Paulie’s rage problem). He breaks Valery’s windpipe with a floor lamp after the Russian gangster calls him a cocksucker.” Christopher is dumbfounded at Paulie’s short-sightedness, but they still have to find a way to dispense with the Russian, who they believe to be long for this world. After bundling him up and throwing him in the trunk, they drive out to Pine Barrens, a rural and heavily wooded area in South Jersey, to get rid of the body.

After Valery — not dead at all, and a trained soldier — fights Paulie and Christopher off and gets loose in the woods, the episode devolves into a exploration of two men fighting nature, becoming reduced to paranoid shadows of themselves by cold, hunger, and anxiety about having botched their mission. The style of cinematography changes as the forest swallows them up. Shaky, handheld camerawork assumes their point of view, gazing up dizzily at endless wiry trees, looking for either Valery — one of TVs greatest red herrings — or their car. Long tracking shots capture them running wildly through snowbanks, disturbing the immense silence of the seemingly endless (in reality, we find out later, only a couple of miles wide), snow-covered woodland.

Buscemi throws the pacing oof the average episode of television off here, as well. We cut back, sometimes, to Tony dealing with Gloria, and Meadow, tracking her then-boyfriend Jackie, Jr., but the focus is Christopher and Paulie. Just (as Christopher puts it) “two assholes lost in the woods,” the two men are haggard, sucking on ketchup packets for sustenance, struggling to build a fire, fighting with each other within an inch of their life (Paulie: “Not bad mix it with the relish!”). In the heat of the moment, the episode manages to be very funny, functioning on some level as a Coen Brothers-esque romp.

In six seasons of The Sopranos, it’s hard to think of another scenario on the show that is as memorable as “Pine Barrens”‘s comedy of errors. Grounded by Terrence Winter (later, the main perpetrator of Boardwalk Empire and today’s catastrophic Vinyl) and HBO regular Tim van Patten’s quotidian dialogue, the episode ranks as a microcosm of what made The Sopranos so unusual. It’s a moment when Chase’s drama broke with continuity and convention in a way that not only made for great television, but created a new potential model for what a TV episode could be, convincingly, in the future.

“Pine Barrens” would find correlates in television of the post-Sopranos generation, some of it on shows which were helmed by writers and directors who cut their teeth on David Chase’s show. But the most direct correlate to the episode — and I’m not the first to mention this is Breaking Bads more overtly pseudo-philosophical “Fly,” a polarizing episode which finds Walter White and Jesse Pinkman, in a sustained situation throughout the episode, attempting to solve a problem they cannot possibly fix. Like Chris and Paulie, they suffer through claustrophobia, paranoia, and naked fear in a confined setting.

True Detective Season 1’s self-contained, lengthy stakeout in the housing complex, Season 2’s sex party sequence, Don Draper’s druggy California getaway in Season 2 of Mad Men — there are numerous other models for episodic, movie-like disruptions in the context of a serial television show. One of the most structurally experimental shows HBO has ever programmed — Damon Lindelhof’s The Leftovers — is essentially a show of only episodic detours, which as a whole, build a fractured narrative around an even-more-fractured world. Last year’s Writer’s Guild Award-nominated Leftovers episode, “International Assassin,” found protagonist Kevin Garvey in a bizarro netherworld much like Tony-as-Kevin-Finnerty’s: Garvey is another version of himself, setting out on a mission he doesn’t understand.

David Chase is known for revolutionizing the serial drama, and yet he claims that his favorite TV series is Rod Serling’s turn-of-the-’60s sci-fi anthology The Twilight Zone. In “Pine Barrens” — as in the Season 6 Finnerty episode Chase found a way to combine the two modes. It’s hard to think of a better single prototype for the style of modern TV drama than “Pine Barrens.” If it wasn’t for daring episodes like it, there’s no way we’d treat our shows of the moment with the same reverence that we do today. The best and least overreaching of today’s dramas wouldn’t be as exciting without the Chase-ean disruptions.