CELLINK Wants to Make 3D-Printed Human Organs Big Business (and They're Not Crazy)

CELLINK is taking the world of “bioprinting” to new heights.

The recent breakthrough in harvesting pig organs for mammalian heart transplants has put the spotlight back on the efforts of many researchers around the world to help solve the world’s organ shortage crisis. But there are other technologies being pursued that are seeking to help alleviate this shortage — some more cutting edge than others.

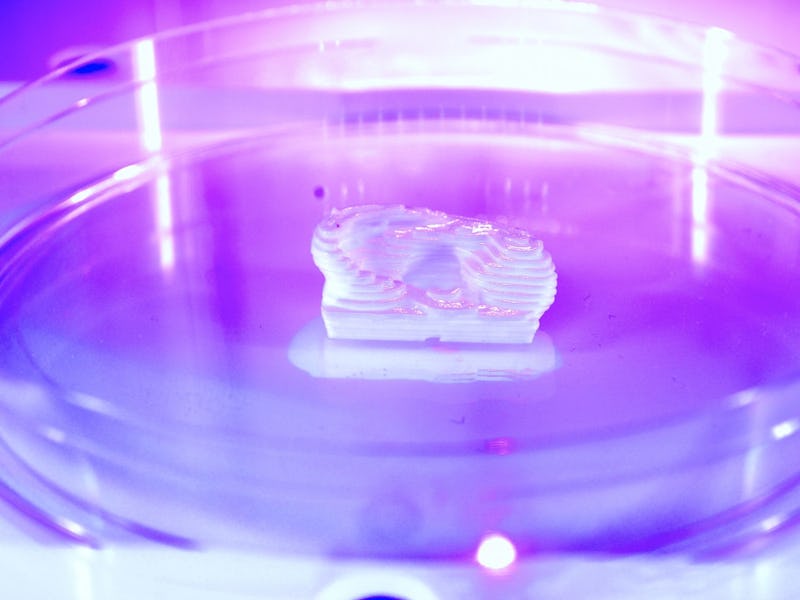

That’s where bioprinting comes in. Bioprinting looks to use the ability of 3D printers to create structures and objects of all kinds of shapes and sizes and turn those devices towards organic materials. And by organic, I mean organic. We’re talking about human tissues and organs that could help replace the need for transplants by allowing patients in need to simply receive a 3D printed organ to replace a faulty one or help speed up the healing process from injuries.

At the Robo Universe 2016 conference in New York City on Tuesday, a startup called CELLINK made the case for bioprinting as the future of organs and tissue transplant, as well as drug research.

A spokesman for the company told attendees to imagine a future where organ shortages were no longer a problem; where no animals were ever harmed in the testing of drugs and cosmetics.

CELLINK calls itself “the first bioink company in the world.” The company is staking its position in bioprinting by saying it can deliver not just the printer needed to create different kinds of tissues — “Anything from skin, to cancer tumors [for studying drug effects], to liver parts” — but also provides the biomaterial needed to create a structure out of living cells.

Most importantly, CELLINK says the biological structures it can print through its bioink are made of cells that survive. In the world of synthetic biology, that’s an extremely difficult feat to achieve outside of a living host. The ramifications would be extraordinarily huge.

Still, CELLINK doesn’t exactly have a proof of concept. The company has conducted studies to demonstrate the viability and efficacy of its bioink, but it’s still a tough sell, as evidenced by CELLINK’s presentation at the conference. The company was vying for a $15,000 first place prize in the Frontiertech Startup Showdown competition, and lost out to Dog Parker, which was able to make a better case on a working business model.

Still, it would be wrong to write-off CELLINK and the bioprinting field as too far out. As researchers — both academic and from private companies — look to make new advances in biomedical applications and research, bioprinting stands a chance to really become a valuable tool. CELLINK’s bioink may be seen by future generations as a forerunner for what medicine eventually evolves into.