What Chinese Movie Audiences Want To See

As the Hollywood machine focuses more attention on China’s box office, the formula for success there is more important than ever before.

Despite a strong marketing push in recent months, Warner Bros.’ Batman v Superman failed to connect with Chinese moviegoers. After a disappointing opening weekend, the film watched its revenue fall nearly 80 percent at the country’s box office in its second week, the largest-ever drop for a Hollywood superhero film. Though the film has grossed nearly $90 million, the DC Universe set-up film has fallen well short of analysts’ $200 million predictions.

It is certainly not the first time that a Hollywood studio has failed to meet the level of success they were expecting in Chinese movie theaters; there have been several recent high-profile disappointments. And that’s kind of a big deal, as in the coming years, success in China is going to be more important than ever.

The second-largest (and growing) movie market in the world is still something of a mystery to Hollywood insiders. To date, it has been seemingly impossible to predict how a film will do in Chinese theaters. Batman v Superman tanked, for example, but last year’s Furious 7 destroyed the Chinese box office competition in one of the year’s biggest surprises.

Well, not surprising if you’ve seen the movie.

In order to gain a little insight into the issue, we asked Prof. Michael Berry, Director of UC Santa Barbara’s East Asia Center and author of a series of books about Chinese Film Culture, what it takes to succeed in the burgeoning, and increasingly competitive, Chinese film market.

The Business of Chinese Film

Over the past few years, the Chinese film market has seen a jaw-dropping 34 percent average annual growth. Last year, the industry closed in on $7 billion in annual earnings, a number that caught the eye of film studios across the world. Unfortunately for the studios, the Chinese film market is also one of the most inhospitable. A mere 34 foreign films are allowed to premiere in Chinese theaters each year, thanks to a quota designed to save the best release dates and most attention for local films.

To get around the quota system, producers have started partnering with Chinese studios to make co-productions like Transformers: Age of Extinction. The tricky part there is that in order to be deemed worthwhile, the film must have equal appeal in both the Chinese and the domestic market. “Thus far it’s been really hard to find a film that will perform equally spectacular in both markets,” Berry explains.

The bright side for Hollywood there is that the Chinese audiences seem much more interested in foreign films than moviegoers are in the United States. “There’s a lot of films that are mega-blockbusters in China that fail fairly miserably in the Western market,” says Berry. “I think Hollywood has been more successful in producing blockbusters that perform well in the U.S. but also in China.”

Monster grossed $385 million in China. In the US it opened to $21,000.

That potential for success is stymied, however, not only by the film quota, but by what Berry refers to as “protectionist mechanisms” designed to support the development of the local film scene.

Pleasing the Guys In Charge

The Chinese government is extremely specific in terms of the films it allows — and it regulates the release dates and even the content that audiences see on screen.

That extra layer of scrutiny is particularly hard on independent films, which, as Berry puts it, “get no action in the box office, because those films are either suppressed or they’re so marginalized,” with a lack of financial support the least of the filmmakers’ obstacles.

“In many cases [the government] will go the extra mile to kind break the legs of independent films and shut them down,” Berry says. “Like, for instance, the last few years, the Beijing Independent Film Festival has been forcibly shut down and has for all intents and purposes been forced to cease operations.

“I know a lot of independent Chinese filmmakers who just ended up going abroad because there was just no lifeline left for them,” he adds. “What’s happening is that Chinese filmmaking is being directed towards this kind of profit-driven, market-driven commercial fare.”

Chinese Box Office Take: $240 million

The Place of Familiarity

Hollywood should beware, because China has been adopting their business model to great effect. The country’s nascent industry is getting much better at producing the kind of profitable films that both look great by Hollywood standards and appeal to the Chinese people on a more fundamental level. That ability to mimic Hollywood’s special effects while providing stories that stem from their culture have made for a tough opponent for foreign films entering the Chinese film market. Never underestimate the market value of familiarity.

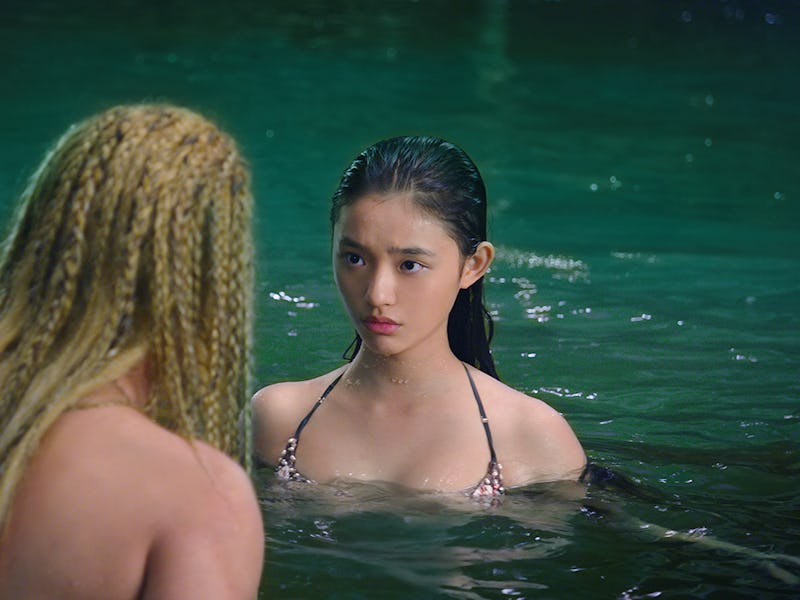

Take, for instance, China’s newest highest-grossing film of all time, The Mermaid, the fantastical story of a mermaid who falls in love with the businessman she’s been hired to assassinate. According to Berry, a large portion of the film’s huge domestic success is the man behind the camera, Stephen Chow. “The Stephen Chow brand is huge,” Berry says. “It’s almost the equivalent of a Spielberg film for the US market. He is probably the most successful purveyor of the action-comedy genre in China. So, there’s a huge cache behind him.”

If you’ve never heard of him, go watch ‘Kung Fu Hustle’ right this minute.

The Mermaid is winning the Chinese box office for much the same reason that, say, Avengers performs well in the United States. Chow takes the collective history and mythology of his homeland and channels it into something “fun and quirky and postmodern,” says Berry. It’s probably unsurprising to discover that Chinese audiences prefer content that they can relate to — that they’ve grown up with — over something with which they’re less familiar.

Naturally, language plays into that enjoyment, too: “Look how poorly foreign language films perform in the US market,” explains Berry. “To this day, the single highest grossing foreign film [in the United States] is Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon which was released in 2000. Sixteen years later, that record still hasn’t been beaten and I think that speaks to a kind of chicken and egg problem where either American audiences are unwilling to accept foreign-language films or studios and distribution companies have decided that Americans aren’t willing to go down that path.”

“China is actually much more open than we are in their willingness to support, you know, Avatar and Titanic and all those films that have performed historically incredibly well in the Chinese box office,” Berry notes. “Still, though, local audiences in China feel more comfortable if they’re watching a film in their native language. They don’t need subtitles, all of the jokes translate. Humor is notorious for not translating as well, say, action or thrillers. Some genres cross boundaries with relative ease, but humor is much more difficult.”

That’s an important note, too, because when it comes to the Chinese box office, humor is big business.

The Place of Escapism In China

The top two highest grossing films in Chinese box office history, The Mermaid and Monster Hunt, respectively, are primarily escapist comedies. They provide something familiar that Chinese audiences can latch on to while also providing a few hours of giggles as a respite from their everyday lives.

“There’s a lot of tension in contemporary Chinese society, there’s a lot that’s taboo,” Berry says. “There’s bans on certain themes like time-travel, certain fantasy genres are frowned upon, anything dealing with politics that’s in any way critical is suppressed, so comedy is one area where you can kind of flourish [in China]. It’s a popular outlet that, in some way, allows people to relieve certain stresses of their everyday lives living in China.”

Historically speaking, that’s only natural. Comedies and escapist adventures tend to thrive in times of great social tension. Perhaps that’s why Marvel’s superhero films, which broad humor and light-hearted tension, tend to perform better in China. Last year’s Ant-Man, for example, was a modest success in America but actually dominated the Chinese box office for two weeks.

The Changing Landscape of Chinese Cinema

“The Chinese film industry is in a somewhat abnormal state right now because theres such a proliferation of studios, there’s a lot of money in China behind the film industry,” says Berry. “It’s like Hollywood on steroids. There’s a huge interest in film in China, but it’s almost completely funneled towards the commercial film model.”

Fortunately for film lovers, though, that may be due to change in the near future. China’s quota on foreign film is up for debate in 2017 and the expectation is high that the country will raise its foreign film quota by a fair amount. Perhaps even more promising, Berry explains that, “There’s been a lot of talk about adding some internal revisions to the quota system that would allow more independent films to have access to the Chinese market. I think that would be a very important step to take because … a healthy film industry can’t just function on Batman v Superman alone. Film comes in many forms, right?”

Still from Chinese documentary ‘The Patriot’

China is right now seemingly on board with giving more liberty to its industry. Last October, the country’s leaders drafted the first film law which was designed to, as Singapore’s TODAYonline put it “ease the censorship process and … boost movie production in the world’s second biggest movie market.”

That doesn’t mean the country is ready to welcome a whole lot of blockbuster foreign films just yet. Last month, Variety reported that China recently announced a tax break to cinemas which “achieve two thirds of their revenues from Chinese films.”

The impact of all this swirling legislation is that the coming years may offer safe harbor to many independent foreign films, while homegrown Chinese blockbusters offer increasing competition to Hollywood’s most marketed fare.

So, What Does It Take?

Hollywood is currently working on the issue of getting their big budget films into the Chinese market, as much for the extra cash as out of sheer necessity. With the increasingly bloated finances of Hollywood films, Berry says, “the challenge is that they have such huge budgets riding on them that they’re dependent on that market, and the global markets to break even.”

That reliance on the lucrative Chinese market has caused Hollywood to rethink its strategy. American films are being crafted from the ground up to cater to Chinese interests as much as they appeal to their domestic audiences. Unfortunately, simply trying to make a film that speaks to Chinese audiences is a tough target to hit. With all the change brewing in the country, what’s popular now may not be so in just a few years.

“The Chinese box office has been growing so quickly, so exponentially, over a very short period of time that it feels like every month or two there’s a new historic box office success,” says Berry. “If you ask me again in a year, I’m sure [Monster Hunt and The Mermaid] won’t even make the list anymore.

So, what does it take to play in Shanghai? What’s true now won’t be in a few years time. Also, it helps to be Stephen Chow.