No, the People Living in the Arctic Aren't Happy About Record High Temperatures

You might think northerners would appreciate a break from the bitter cold. You'd be wrong.

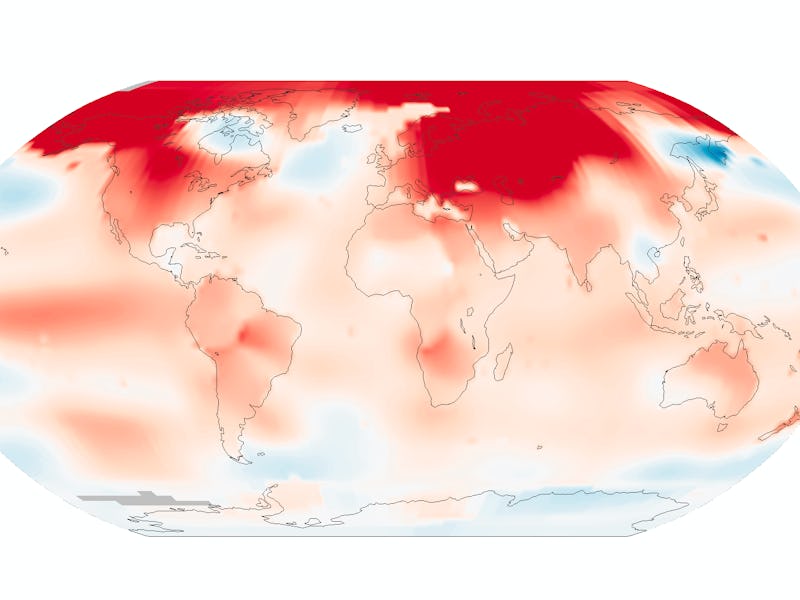

It’s an understatement to say that the global temperatures over the past year have been off-the-charts-bananas. The last ten consecutive months have broken monthly temperature records. February 2016 smashed the record so completely that it earned the dubious honor of being the most record-breaking month ever recorded (one climate scientists described the data as looking “like something out a sci-fi movie”). The causes of this meteorological freakshow included a monster El-Niño and ever-mounting effects of global climate change.

While basically all of North America has been impacted by the unusual warmth, nowhere has it been as dramatic as in the northwestern bits of the continent — in Alaska and Canada’s Yukon territory. Here’s how shockingly warm it was in Whitehorse, Yukon: In February, the thermometer never dipped below zero Fahrenheit. The average daily low in February from 1980-2010 was minus two. In a place that is used to temperatures dipping to -40 Fahrenheit at least once or twice, the coldest morning all winter was just -27.

You might imagine that the folks living in the Arctic and sub-Arctic are pretty thrilled about the break from long, blisteringly cold winters. They aren’t; not exactly. Sure, -40 temperatures make going outside unpleasant, but a mid-winter thaw is even worse.

The thing about living in the northern latitudes is that, to survive the winter, you find some activity you like to do outside, like cross-country skiing, snowshoeing, or snowmobiling. “I certainly took advantage of the warmer weather to spend a lot more time outdoors this winter, either hiking, snowshoeing or walking the trails,” Whitehorse resident Myles Dolphin told me. But once things get above the freezing mark, there’s a whole new set of problems. A lot of those activities get impractical or downright hazardous.

Alaska and Yukon have two major annual dog-sled races, they Yukon Quest and the Iditarod. Sled races are particularly sensitive to warm temperatures, since they require lots of snow and also safe travel down frozen river corridors. It’s not good for the dogs, either, who overheat quickly while running if temperatures creep above zero. Both races had to shorten and reroute their their courses this year to avoid sections of low snow and dangerously thin ice. Alaska shipped 7,000 gallons of snow by train to Anchorage for the Iditarod’s ceremonial start.

In the North, frozen rivers and lakes become winter highways, both for recreation and mundane transportation. Canada’s Dempster Highway goes 150 miles farther in the wintertime, thanks to a frozen road that crosses and travels along icy rivers. Summer ferry crossings become ice bridges. Many residents depend on very cold weather to safely travel within the region. Warm weather is bad for safety, and bad for fun.

“This winter I did some snowmobiling in the back-country in the Dawson area,” says Whitehorse resident Duncan Smith. “Travel on the Yukon River has been worse than normal with more than usual overflow and larger patches of open water. Also, a trip from the Dempster Highway to the Yukon River via the Fifteen Mile River had to be aborted because the upper Fifteen Mile just had too much open water. Had it been a colder winter the creek would have been passable. Warm winter equals bad travel.”

The Arctic is warming twice as the rest of the world in response to climate change. Already, Alaska and Yukon have seen a six-degree average increase in winter temperatures. A thawing North presents enormous infrastructure challenges as permafrost melting sinks buildings and destabilizes highways. A lot of people assume that cold winters make the North unlivable. For people who have learned to enjoy the snow, that’s just not true. Actually, it’s the end of cold winters that pose the biggest threat to Arctic life.