Could a Video Game Designer Win a Nobel Peace Prize? Yes, Sooner Than You Think

Studies show that games make people happy and teach integral skills. The time for laureates is now.

Jane McGonigal has a bold vision but not an outrageous one: She predicts that by the year 2023 a game designer will be nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize. A game designer herself, McGonigal says a Peace Prize win is her “#1 goal in life,” a goal she’s pursuing by both designing games and trumpeting their current and potential importance on the collaborative design platform Gameful. Is her quest ridiculous? Only in that the Peace Prize is generally an incidental benefit of a person’s selfless striving on behalf of humanity. There will be a Nobel Prize-worthy game.

The question of when that game will arrive is more about the Nobel Prize system than games as an art form. In order to secure a nomination, a game maker would have to be working towards building “fraternity between nations”, decreasing militarization, and promoting peace. People can only be nominated by a select group of people, including but not limited to, professors of social sciences, active and former members of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, and people who have previously been awarded the Peace Prize. And winning is really hard. There are 376 candidates for the 2016 award, 228 of which are individuals and 148 of which are organizations.

There’s a reason it is considered the most prestigious prize in the world.

While video game developers aren’t typically considered in the same category as Malala Yousafzai or the Tunisian National Dialogue Quartet, their work can’t be discounted. Social psychologists have long thought that games, at least in the traditional playground sense, promote creativity and and conceptual understanding. Meanwhile, game theory posits that games build up cognitive strategy skills appeal to the very mental processes that make us human. Games are, in short, a potentially powerful tool for peace and understanding. They just haven’t historically been used in the pursuit of those ends.

Social science tells us that the peacemaking game is more of an inevitability than a beautiful dream. Much like child’s play allows children to work out and practice simulations of real conflicts, video games have been proven to provide cognitive and problem solving skills, while teaching players how to coordinate and cooperate with people. While a lot of psychological research — an absurd amount really — has focused on the “violent” aspects of gaming, that’s a problem with the content, not the medium. Evidence proves that games can make people better.

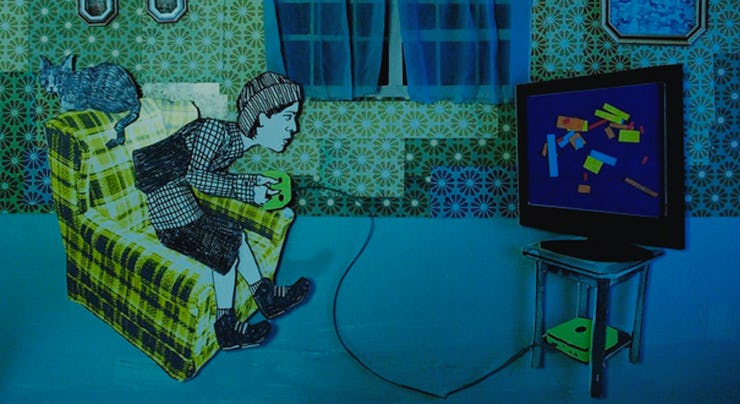

Over the past five years, more and more researchers have begun to look at the positive affects of online gaming. This isn’t your alone in the basement world of gaming any more — in a 2014 edition of American Psychologist researchers from Radboud University Nijmegen in the Netherlands point out that “perhaps the biggest difference in the characteristics of video games today, compared to their predecessors of 10 to 20 years ago, is their pervasive social nature.” Over 70 percent of gamers play with friends, particularly when it comes to multiplayer online role playing games, like World of Warcraft or Halo. On a research level, researchers have found that these games teach people integral social scenes. On a personal level, to those who play, it’s obvious.

In their paper in American Psychologist the Dutch researchers break down the benefits of gaming into cognitive, motivational, and problem solving skills. They found that the games that make people think most effectively are those that operate in “visually rich” 3-D spaces, where players have to use split-second decision making. Problem solving skills are typically developed in all games, but particularly ones that involve action sequences based on memorization and analytic skills. These skills lead to prosocial, helping behaviors that have demonstrably been found to stick around for the long haul.

But the motivation that games bring out in people may be the strongest argument for why a game could possibly make the world a better place. Games are one of the few instances where people persistently face failure but want to keep going. This effort, psychologists agree, is what you need to realize success and achievement.

Games affect cognitive, motivational, and social abilities.

There may not be a game available now that is deserving of a Nobel Prize, but it’s not for lack of trying. McGonigal’s own game, SuperBetter, was designed to boost physical, mental, and emotional resilience. And it works: In a month long, randomized trial at the University of Pennsylvania, subjects with depression who played the game saw their depression decrease by 12.9 points while those who didn’t get to play the game had their depression decrease only by 5.1 points. Generally, it only took people 30 days of playing the game to report that they felt less anxiety and more happiness.

But SuperBetter is by far not the only game trying to change the world. There’s the Self-Esteem Games project at McGill University designed to, yes, help people have a better self-esteem. Foldt, an online protein folding game, was able to identify a gene structure that had eluded researchers for over a decade after the designers encouraged the game’s quarter million players to figure out how to stabilize different strings of amino acids. Depression Quest, Evoke, Way — all games where the goal is to create a social good by taking a virtual situation and putting it in a real-world context. Maybe that’s not enough to be nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize now, but it certainly doesn’t mean that there’s no chance that won’t happen in the future.