'Game of Thrones' Season 6 Needs New Plotlines Super Bad

The Starks, Lannisters, and Targaryens will only get more fascinating once they graduate up Maslov's hierarchy of needs

The first pivotal moment in both the Song of Ice and Fire books, or HBO’s Game of Thrones, is the death of Ned Stark, a character who, in any other fantasy story, would have served as the long-term protagonist. In chopping the Stark patriarch’s head off, Game of Thrones taught its audience how to watch the show: with baited breath and white knuckles.

Stark’s children were plunged into chaos without him, and the show made very clear that each of them was equally likely to be culled in subsequent episodes. The problem is, as the show developed, writers became increasingly focused on death as the end-all plot line. Suddenly, avoiding a violent death became the most important objective for each character, and that became boring.

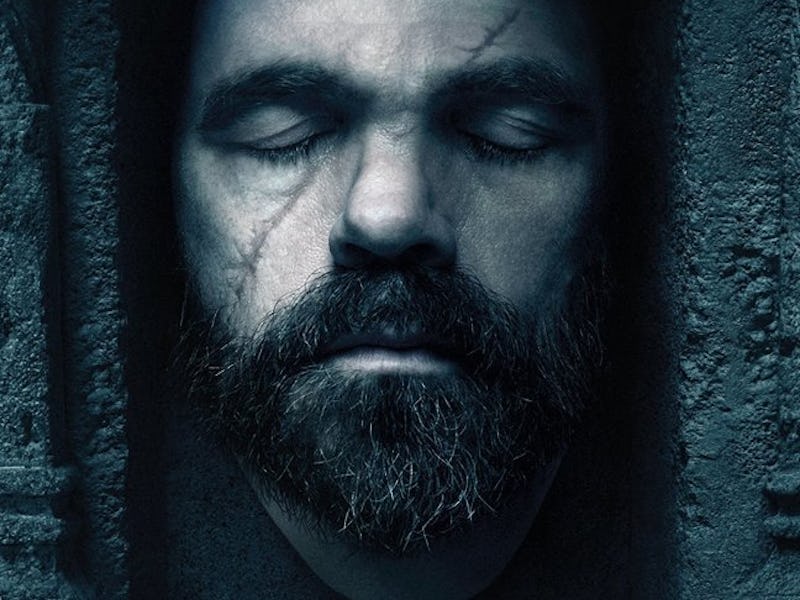

Now, Game of Thrones fans face a new season promoted solely by death-themed posters and trailers. Though the book series’ central questions are about power, lineage, guilt and family, the show has become a well-costumed, well-scored ode to the Grim Reaper. Game of Thrones deserves more.

The Stark progeny, ironically, have fared pretty well since their father’s death. Granted, one of them is dead, and another is dead-question-mark, but the others have been shuffled all over George R.R. Martin’s world and endured various ailments. They still have agency, and this upcoming season will likely see Sansa and Bran, specifically, grow into more powerful and influential chess pieces. Their strategies, shortly after their father was killed, amounted only to surviving in a hostile society, but now that they’ve each gained some ground, running from imminent danger, they’re refocusing.

Sansa is now the eldest Stark — that she is aware of — and the show will benefit from her pursuing power with the same hunger she once pursued a husband. Arya and Bran have turned, recently, to magic, and can carve out pivotal roles for themselves using their otherworldly skills. Watching them do this will be infinitely more interesting than waiting around to see who’s going to stab either of them when they’re unprepared.

Game of Thrones isn’t a stabby show; that’s what made it so shocking when it began. In early episodes, critics called it The Lord of the Rings fused with The Sopranos, an apt descriptor, considering the undulations of Tony Soprano’s psyche were considerably more important than murder. Game of Thrones already has the scaffolding for psychological intrigue: characters like Littlefinger, Tyrion, Varys, Margaery and Cersei are made multi-faceted and dangerous because of their emotional capabilities. There will always be a part of Game of Thrones’s appeal fixated on scenes like Tywin being shot to death on the toilet, but far greater is the series’ exploration of emotional warfare. Killing Jon Snow in the final episode of its fifth season did several things to Game of Thrones overall.

Foremost, the Stark bastard’s death made HBO look bloodthirsty; you can almost imagine a dartboard of character faces in the writers’ room, surrounded by a ring of scriptwriters holding darts, salivating. Second, it set in motion several fan theories desperate to link Jon to the Targaryens. Despite all of Game of Thrones’s addictive nihilism, its fans retain hope for a Targaryen uprising. That hope is what made the show’s connection between Tyrion and Dany feel so cathartic; we wanted to believe the two blood-soaked good souls could find meaning in the madness, together. More deaths will only work to negate this reading of the series, and that isn’t a good thing.

We’ve written at length on the subject of fiction writers doling out dopamine to their readers and viewers, but HBO has made a spectacle out of its largest program using the opposite tactic. How often does a Game of Thrones episode leave a bad taste in the viewer’s mouth — everyone I know was depressed post-Mountain v Viper, for days! — and how often does it tease the viewer with the success of a character like Brienne, the redemption of a character like Jamie, or the desperate and tearful act of a downtrodden soul like Theon?

As the show moves into its first season untied to the source text, it must not focus completely on which characters live or die, but instead on the politics of its world, and the development of its lore. Death after bloody death isn’t transcendent fiction, it’s a public hanging. Remember how those went out of fashion?