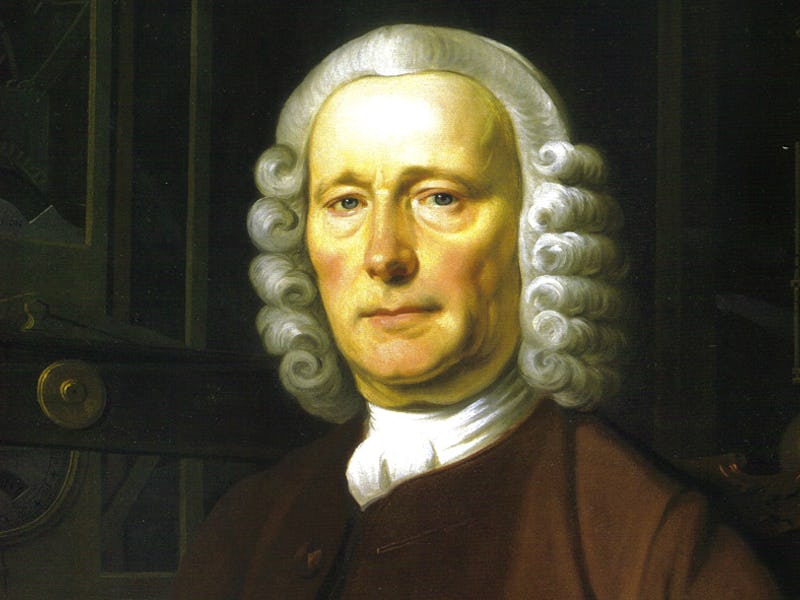

Longitude on Time: How John Harrison Defeated Dumb Science to Save Sailors

John Harrison created a device that helped sailors find longitude at sea, but it took another 250 years before he'd get credit for his most amazing invention.

Following the Scilly naval disaster of 1707, which lost four British Navy ships and almost 2000 sailors at sea, Parliament decided sailors needed a better navigational tool. The British government passed Longitude Acts, which were essentially cash prizes offered by the government to entice the best minds of the era to solve one particular problem: ocean rocks. The idea was to stop hitting them and the best way, everyone figured, was to figure out how to calculate the precise longitude of a ship at sea. While latitude was never hard to figure, longitude had stumped captains for, well, ever.

Luckily, for anyone who has sailed a ship (or flown a plane) since, an English carpenter and amateur clock builder named John Harrison got to work.

In 1727, Harrison traveled to London to see about cashing in on the Longitude Act challenge (about $5,000,000 in today’s money). He had this theory that instead of fumbling around with star charts, you could find longitude by telling time; more accurately, if you keep a standard time (Greenwich Mean Time) and then the time of wherever you are on the globe, that difference can then be used to calculate longitude. Of course, to do that, you need a clock. And not just any clock, but a super kick ass clock that could stay accurate as it got tossed and turned on the open sea.

John Harrison's H1 clock

Harrison, who had already gained a reputation for building fairly accurate clocks using nothing but wood, spent the next seven years building his “H1” clock. After testing on it rivers, Harrison finally got his chance to test it at sea aboard the HMS Centurion on a trip to Lisbon. As the story goes, Harrison had some troubles early on, but by the end, not only was the clock working smoothly, he actually saved the ship, which had gone a whole 60 miles off-course.

Naval officials were impressed and soon Harrison found himself in front of The Board of Longitude to see about getting his hands on some of that prize money. Unfortunately, The Board of Longitude was made up of astronomers who were really not digging a solution that ignored stars. However, they were amused by what they called Harrison’s “curious Instrument” and peeled him off £250 with the promise of another £250 if he could produce an improved version in two years time.

Harrison worked on his new and improved clock for over three years, and just when he thought he had it solved, he discovered a pretty nasty flaw: the yawing motion of the ship threw off the accuracy in a major way. Undeterred, Harrison spent the next 19 years trying to come up with an improved version of his second design, only to scrap the third version altogether.

But Harrison was not the type of cat to let physics or a quarter century of pulling his hair out stop him from getting £250 and a place in history. Harrison realized that one of his major flaws in the balance of his first three designs had to do with the sheer size of the clocks. In 1751, he devised a smaller model and had it encased in what looked like a large pocket watch. He had his son take it on a voyage to Jamaica, and the captain of the ship was so impressed, he offered to buy the invention on the spot.

Harrison's H5

In fact, the testimony and records from the trip were so sterling, The Board of Longitude claimed that no clock could be that accurate, claimed the test and results insufficient, and denied Harrison any further prize money. Harrison and his supporters raised a stink and actually complained to the King about what he saw as unfair (and fairly petty) treatment by the Board. With the King’s blessing, the Board of Longitude agreed on another round of testing (this time with Harrison’s new and improved H5).

This time, proof of the accuracy of Harrison’s chronometer was irrefutable; the clock was accurate well past the specifications set by the Board. However, in spite of Harrison’s victory, the Board decided to award Harrison £10,000 with another £10,000 to be paid in installments only if it was proven that other clock manufacturers could build the chronometer according to Harrison’s specification. Harrison went apoplectic that he should have to share his trade secrets with other manufactures, and spent the rest of his life fighting The Board of Longitude, his competitors, and just about everyone else who dared to deny his genius.

Even though the King of England got Parliament to agree to pay Harrison a fairly healthy stipend for his “service to the crown,” Harrison wasn’t done. After 60 years of trying to build the world’s most accurate chronometer, Harrison drew up plans for what he proclaimed would be the world’s most accurate land-based clock. Such a clock might have been considered his greatest invention if he hadn’t decided to introduce it in a book that was basically a slap in the face to every last one of his competitions and detractors.

The book was so inflammatory that even his supporters distanced themselves from the once-revered inventor. His enemies began to take very public victory laps; insulting the clockmaker and his work as “an incoherence and absurdity that was little short of the symptoms of insanity.” Harrison died not long after the book was published, a pariah in the scientific community. The plan for his final clock would go forgotten for the next 250 years.

250 years later, Harrison's clock sets accuracy record

Last year, scientists debuted the first prototype built to Harrison’s exact specifications. After running for 100 days, Harrison’s ultimate pendulum clock was only five-eighths of a second off, making it the most accurate mechanical free-pendulum clock ever created. The man who invented the chronometer, which revolutionized navigation and accelerated the Age of Discovery, had to wait over two and half centuries, but he finally got the last laugh.