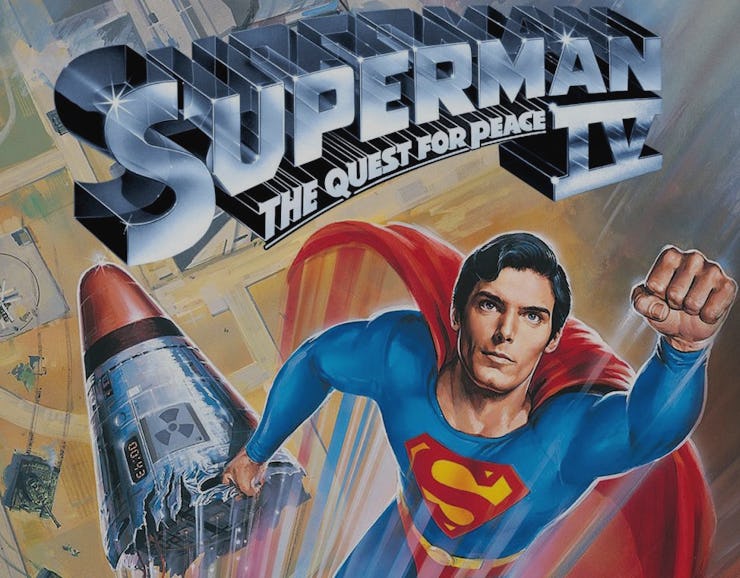

How the Shady Business of 'Superman IV' Sidelined the Man of Steel for 20 Years

Inside the 1987 box-office disaster that jeopardized the fate of heroes everywhere.

The Dark Knight may get a few blows in this week as Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice hits theaters. But there is no way the Kryptonian defeat will be as absolute as the one served in 1987, the year Superman IV: The Quest for Peace proved the fragility of what seemed to be an impervious franchise.

Fans’ palpable uncertainty about Batman v Superman is understandable, given the sequel’s tone (goth kid-bleak), run time (in keeping with its title), and purpose (setting up a coherent DC Universe for Warner Bros.). The alternative, though, doesn’t look much better. Superman IV, a film in every way the opposite of BvS, was so disastrous that it melted the Man of Steel’s big screen career for a full two decades.

Here is an up-close account of how that cinematic disaster went down.

“I practically wept at the end. It was tragic.”

The first Superman film, directed by Richard Donner, was an absolute sensation when it released in 1978, and made a star out of Christopher Reeve. The sequel was also a success, but one marked by infighting, lawsuits, and bitterness. After the poor reception for 1983’s Superman III, which was made without stars Gene Hackman (Lex Luthor) and Margot Kidder (Lois Lane), it looked like the franchise had hit a wall that not even Superman could smash through. The Salkinds, the family that produced the first three films for their part, were definitely done with the Man of Steel.

“I think they were smart enough to know that it had run its course,” Harrison Ellenshaw, the veteran visual effects supervisor who worked on the fourth film, remembers. “And the third one was awful. It’s tough doing more than one sequel.”

That’s when the Cannon Group entered the picture, and made things immeasurably worse.

There are really two types of B-movies: The good ones, exemplified by Roger Corman’s long, beloved oeuvre; and the bad ones, like the schlocky ‘80s knockoffs, exploitation and skin flicks made by Cannon. A B-flick factory run by two Israeli cousins, Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus, Cannon was responsible for the endless Death Wish sequels, the rise of Chuck Norris, and too many unnecessary nude scenes to count. In the mid-80s, using foreign-rights money and a lot of borrowed cash, they made a play for legitimacy; their plan included optioning the rights for Superman movies and convincing Warner Bros. to distribute another sequel.

Everything hinged on Reeve returning for a fourth go-round in the underoos, a proposition that at first seemed unlikely. But even Superman has his price, and in exchange for financial support for his passion project (the journalism drama Street Smart) and the opportunity to write the story for the new Man of Steel adventure, Reeve agreed to sign on. He even got Hackman and Kidder to return for the film, which he decided would be about nuclear disarmament. Things looked sunny again in Metropolis. For a short time, at least.

“It should have been a win-win-win for all concerned,” Ellenshaw says, who made his name providing effects and paintings for the original Star Wars films. “I practically wept at the end. It was tragic. There were so many people devoting so much. But that’s movies, no one sets out to make a bad one.”

The gist of the story was that Superman had decided, after the U.S. and Russia couldn’t come to a disarmament treaty, to take matters into his own hands and rid the world of all nuclear weapons (via a gigantic net in space, like a nuke fisherman). Lex Luthor, recently freed from jail by his dim valley-boy nephew Lenny (played by a ridiculous Jon Cryer), saw an opportunity to get into the arms trafficking game, and to take out his do-gooding arch-rival, invented an even more powerful super-villain: Nuclear Man, created using a strand of Superman’s hair attached to a nuclear weapon that was rocketed into the sun.

Sure, the premise was a bit hokey, but the real problem was a lack of resources to pull it off.

“How are you going to do that?”

In a way, the project was doomed from the start. Despite all the advertisements they took out in Variety and boasting they did about affording the film a healthy budget and first-class production facilities, Globus and Golan had no intention of supporting director Sidney J. Furie’s film with any special treatment.

“They didn’t know what the movie was when we were in production and Menahem would get it confused with other movies,” Ellenshaw remembers. “On the few times he would come over to England — he never showed up on the set — we’d have to visit him and eat grapes in his hotel suite. He’d talk about the underground sequence, and Sidney and I would say, who’s gonna tell him there’s no underground sequence in this film?”

And while the producers boasted of giving the movie a $30 million budget, that number was slashed over and over again; Ellenshaw estimates it was really closer to $13 million. There was no underground sequence, but the film that Reeve devised did call for plenty of complicated shots.

The Fortress of Solitude set

“Unfortunately it had more effects than all the first Superman movies combined, and I had to do them in a hurry,” he says. “If I had said I’m not going to do them unless we had more testing, they’d say, ‘Thanks a lot, don’t let the door hit you in the butt on your way out.”

After Superman destroyed Nuclear Man, they had Luthor create a second, more powerful Nuclear Man, but couldn’t explain why this long-clawed Aryan monster wanted to fight Superman at locations across the globe (other than the fact that’d it look cool, in theory).

“You read in the script, ‘He picks up the Statue of Liberty and throws down Fifth Avenue,” Ellenshaw recalls. “They’d look at breakdowns of script and look at me and say, How are you going to do that?’ You’re in a meeting and think, I should have been a heart surgeon.”

Of course, all the international locations — which Ellenshaw says were constantly rewritten — were blue screened, and it often looked like the two heroes were fighting in front of a wall (they were).

“This is what happens when you cut back on scripts,” he says. “A lot of people, including the writers and often the director, come along and say, ‘I’ve got another idea!’ But none of those ideas were any cheaper?”

Cannon’s tight-fistedness also hurt the production the few times they were allowed to shoot at physical locations. Most notably is the scene in which Superman marches across 42nd street to the UN, which was actually just a dressed-up plaza in the dreary post-war concrete city north of London called Milton Keynes.

Even worse was a sequence that Ellenshaw says “will haunt me until I die.” The scene sent Superman and Lois on a joyride around the world, a trip that made it seem like that Lois had discovered his secret identity. Obviously, they couldn’t have that — that would have blown up the goofy double date scene between Clark, Superman, Lois, and a new love interest played by Mariel Hemingway (who takes Clark on a quintessentially ‘80s aerobics date).

But instead of cutting the flying scene (which was really just a bad version of a more romantic flight in the original film), they decided to completely make up a new, temporary power for the hero. “The writers weren’t around, they were back in Hollywood, and there’s Chris and Sid and everybody’s kinda going, ‘I dunno.’ And they decide there’s a kiss and it’ll be done,” Ellenshaw remembers. “He kisses her and the memory goes away. Where’s that rule written in the Superman world?”

Hint: It’s not.

“You Have a Week”

Even as things seemed disastrous, Reeve’s optimism kept the set hopeful that they’d end up with a decent film; after all, Hollywood is filled with troubled productions that become iconic films.

“Probably because, everyone has to get on board and has be committed, you never lose hope,” Ellenshaw says. “Even when the iceberg is getting close you think we can still will ourselves into making a good movie.”

Unfortunately, that just wasn’t the case here.

After they limped to the finish line, Furie turned in a 134-minute rough cut to the suits at Warner Bros. The studio, which was distributing the movie, hadn’t had much involvement in the production, which led to a disastrous preview screening.

“It was a total frickin’ disaster,” Ellenshaw remembers. “The report came back to the heads of Warner Bros. and they said ‘OK Sidney, we need to take a look at this movie.’ They looked at it, and said ‘Cut half an hour’. And Sidney, who was always very staunch and said no one can mess with my cut, said ‘OK, we���ll trim it. We�����������������ll keep the essence, we may have to do a couple reshoots.’ And they said, ‘No, lose half an hour — and you have a week.’

A broadsword was taken to the film without much consideration of plot, pacing, or character development. Most notably, they cut out all mention of Nuclear Man 1, whose defeat should have been a pivotal moment in the film and driven the action in the second act. It also meant that Ellenshaw lost 200 of his 600 effects shots, which meant his small budget was effectively wasted by a full third. Post-production was also hamstrung by a power struggle within Cannon, which hired a new VFX chief who meddled at every opportunity.

The hacked up movie (the LA Times said the editing took on a meat axe fervor, which was shot and released in under a year, came out in July, 1987. It was a bomb with both critics and moviegoers, who virtually ignored the film; it was out of theaters after just three weekends, and made just $15 million at the box office in the US, compared with the $134 million brought in by the original.

“They put Chris and Sidney and the producers in a hell of a bind,” Ellenshaw says of Cannon. “They knew Chris would never walk away, he signed on the dotted line, and it’s a train wreck waiting to happen. It really pisses me off in hindsight. These guys were creeps.”