Why Haven't We Figured Out How to Make Films About Internet Research Yet?

Next to making hacking look cool, depicting Googling is one of filmmaking's biggest hurdles.

Research montages have always been tricky for filmmakers. Even before the rise of the internet, when protagonists searched frantically for information in libraries and record rooms. Spotlight, this year’s Best Picture winner, featured several high-stakes scenes of paperwork rifling, photo-copying, and dizzying databases. Perhaps the film’s most impressive achievement was making a research team’s search for text documents — church schedules, books, settlement papers — into a thriller. Then, even more thrilling, is the team’s own text document, a newspaper article.

Spotlight benefitted from its period of origin. That is, if a film hopes to weave a narrative about contemporary journalists breaking a scandal, it would have to include screens, Google searches, emails and text messages aplenty. Though some television shows, including Sherlock and House of Cards, have developed their own cinematic shorthand for text messages, internet communication still looks cheesy or dated when it’s onscreen. There aren’t many films that use the Internet in a stylistically attractive manner.

Research scenes need to be embedded into a film’s story in order to not feel like a waste of time. Take Philadelphia, which was released in 1993. The film featured a scene in which Tom Hanks’ character Beckett spends an evening in the public library researching HIV law. The movie uses a research montage, familiar to all fans of contemporary cinema, but the footage of Beckett turning pages and reading passages is interrupted when Beckett notices people in the library are watching him with fear.

Two things are happening here: first, because Philadelphia was released in the early ‘90s, it makes sense that its main character would use the library, as opposed to the Internet, for extremely private research. Second, the film uses this research montage, usually a difficult segment in any film to manage with grace, to further the plot and increase Beckett’s social isolation. It also allows the film’s other main character, Miller (Denzel Washington) to witness Beckett’s loneliness and decide to step in as his attorney.

Philadelphia packs its research montage with so much purpose that the film doesn’t suffer for it; many subsequent films simply employ a boring series of shots in which a character looks at microfiche, dusty old books, or, more recently, Google image results, set to menacing music. Though most of us spend a majority of our waking lives looking at screens, we haven’t figured out a way to frame this experience in an organic-feeling way.

Tony Stark in the Iron Man films uses 3D screens in order to keep the film’s audience engaged in what he’s doing. In the courtroom scene in Iron Man 2, Stark uses a combination of his smartphone, Jarvis and the room’s available screens in order to demonstrate his abilities as a hacker. Though the scene does a decent job of communicating Stark’s tech abilities, it still looks like a science fiction-y process, as opposed to something many of us experience every day.

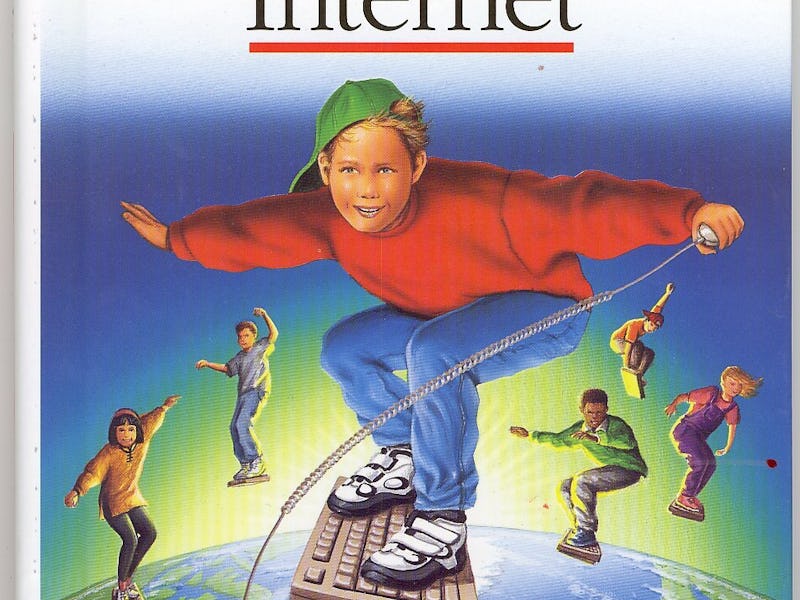

In his YouTube series Every Frame a Painting, Tony Zhou analyzed the tactics contemporary filmmakers have used in order to use texts and Internet searches cinematically. Though he includes quite a few examples of well-rendered text messages in television, he’s unable to point out Internet research working well on screen. He identifies a void between cheesy, dated-looking Internet search scenes in The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo and Hackers and desktop media like Unfriended, 2010’s Internet Story and that one quasi-experimental episode of Modern Family.

Zhou doesn’t quite get to this point, but he’s right on the edge of it: most of us don’t live our lives alongside computers as if they were separate, or alien, entities. We are technically becoming cyborgs, beings who are part computer and part human. We are humans who have meaningful interactions with other humans by way of the Internet. The cultural change is happening so rapidly that our fictional media hasn’t quite caught up.

Though there are many films about the human stories behind the Internet — The Social Network, We Live in Public, and Snowden are all examples — films about the human-Internet experience will have to borrow stylistic imagery from cyberpunk mainstays like Ghost in the Shell and even The Matrix in order to illustrate our shared experience with accuracy.

We know Internet research scenes can’t feature concerned-looking actors with words and web addresses flying around their heads, but the shot-reverse-shot tactic, in which we see an actor’s face interspersed with shots of a computer screen, isn’t the most attractive option either. Portraying an actor as entering the Internet, as if it were another world entirely, is probably a little closer to the truth.