Doctors Create a New Jaw For A Girl Born Without One

Her almost-fatal condition was one in a million.

Midway through her mother’s pregnancy, doctors noticed that Alexis Melton’s lower jaw was drastically, dangerously small. Amniotic fluid was building up in her mother, Lisa Skylynd’s womb, drastically altering what had previously been a normal pregnancy.

Alexis, or Lexi, was born at only 34 weeks, and diagnosed with an extremely rare condition called auriculo-condylar syndrome — her lower jaw was essentially a tiny mirror image of her upper jaw, fused to her skull and blocking her windpipe. Doctors from Seattle Children’s Hospital performed an emergency tracheotomy, installing a breathing tube that she needed until she was three.

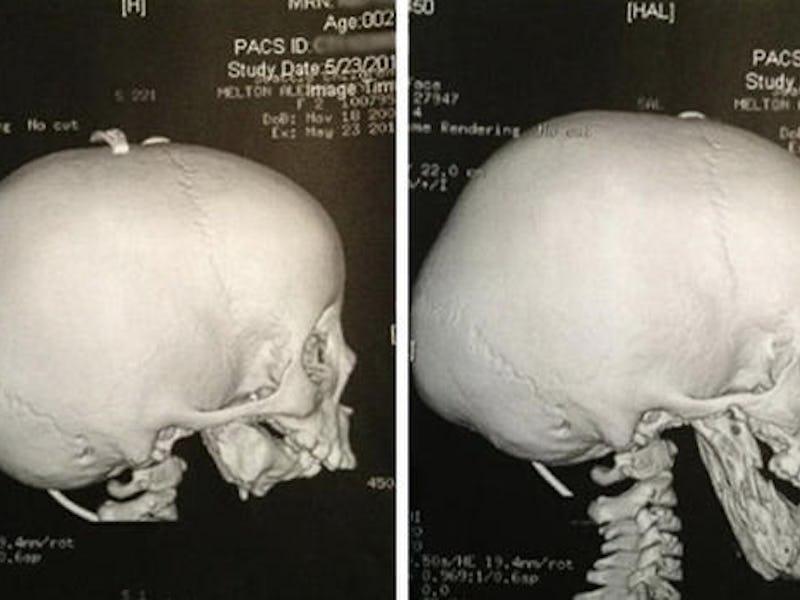

Lexi's jaw at birth, left, and after the doctors' reconstruction.

Living with a tracheostomy isn’t a sustainable solution, especially for a small child.

“A tracheostomy is like only being able to breathe through a big straw that’s prone to having problems at any time,” Dr. Richard Hopper, surgical director of Seattle Children’s Craniofacial Center, and Lexi’s surgeon told Seattle Children’s Hospital’s Pulse news blog. “That burden and worry on a parent is unimaginable.”

To get the tracheostomy out, doctors had to construct a new jaw. They used bone from Lexi’s lower ribs, fusing it to her lower jaw to create enough of a structure to slowly pull the bones apart, opening the airway and slowly growing a new jaw. The procedure is called a trans-facial mandible distraction, a long process where metal pins were installed into the rib and jaw bone tissue and then slowly cranked apart by a device Lexi’s parents used.

“It works like the winding of a clock,” Hopper said. “Twice a day her parents needed to turn the device and it gradually formed new bone. We essentially took her old jaw and made it into a new jaw.”

Lexi before and after the mandible distraction.

By the age of four, Lexi’s airway was open and she could breathe. She’s now seven, and can breath, speak to some degree, and exercise normally (she loves Irish dance and skiing). She still eats through a feeding tube, but is otherwise a normal elementary school student.

Lexi now, at age 7, shows off her smile.

Doctors say another procedure, in 2017, could reshape the joint between her lower jaw and skull, which would allow her to chew and swallow normally, although she would need to train the muscles in her throat to do so. Before reconstructive surgery, Lexi’s condition would likely have been fatal, but new surgical techniques and medical technology are rapidly making innovations in tissue replacement.