The Prejudiced Brain Is the Slow Brain

For years, scientists thought an unknown brain mechanism triggered prejudice. They were wrong.

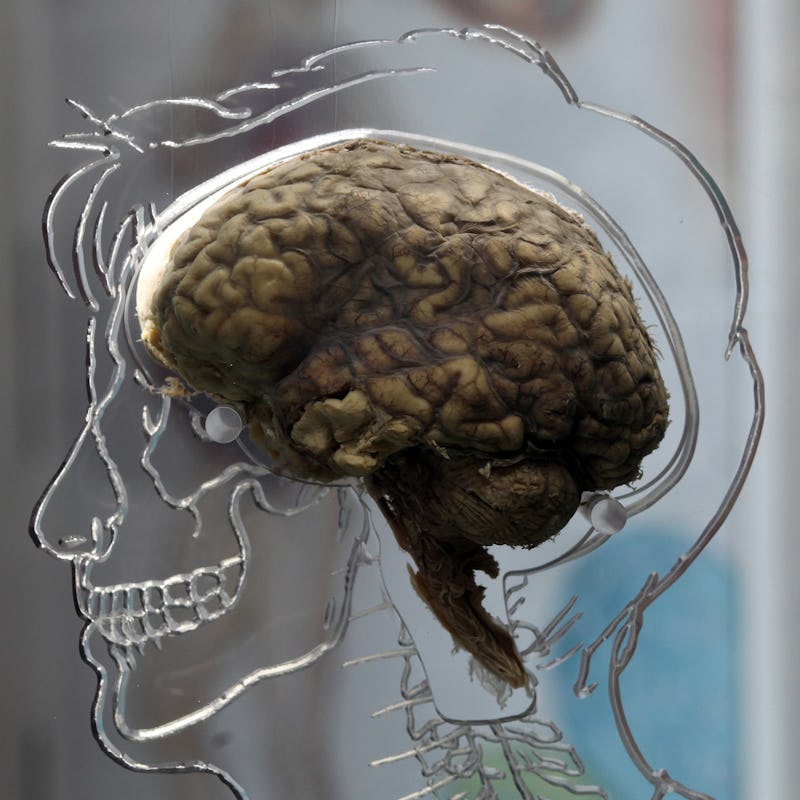

Study after study shows that we are all a little prejudiced. And although neuroscientists have long known that prejudice is a pervasive aspect of human cognition, they don’t really know how the brain tries to overcome bias. A new study from the University of Bern in Switzerland reveals that even when we try to subdue our implicit prejudices, it doesn’t work: Our brains work the same, only slower.

It’s a departure from a previous theory that a secret mechanism exists in the brain, something that turns on, triggering us to have a slower response when attempting to be nice about something we dislike. That’s not, however, what the new research suggests.

The University of Bern team had 83 test subjects — either die-hard soccer fans or political supporters — go through an Implicit Association Test (IAT). The 20-year-old IAT test has users rapidly attribute descriptors to concepts (like people), in order to measure attitudes and beliefs they may not willingly report.

Although there are the obvious, explicit racists (the Donald Trumps and the Donald Sterlings), this study addresses more implicit bias. For example, some people sincerely don’t want to be racists, but when put in a neurological behavior study, they turn out to be just that. In the experiment, the prejudice wasn’t race. Rather, there’s the politician you despise or the sports team you root against.

What they found was that the brain has a delayed response when it has to associate a positive word to something you inherently dislike — like you’re a Panthers fan who has to call Peyton Manning the “greatest ever.”

Hated.

The brain goes through seven processes in less than one second when a word is shown and when the button was clicked. But the reaction time between associating a positive word to a disliked group was slower — not because another process in the brain is activated, but because these seven processes just take longer to happen.

This study is the first time researchers have been able to figure out the chain of mental processes that happen during an IAT test. The team, led by Professor Daria Knoch, analyzed the data by conducting what they call “microstate analysis”, which allowed them to look at the brain both temporally and spatially.

While we can try to subdue prejudices, an IAT test is going to reveal the ugly truth. Darker still, we now know that it’s our regular way of thinking that runs the whole process.