Doctors Gone Wild: 6 Incredibly Popular, Incredibly Brutal Medical Procedures

In retrospect, these treatments are appalling. At the time, they were just what doctors did.

The history of medicine is a mess of unsubstantiated science, pseudo-religion grandstanding, and overzealous amputation — a many millennia old narrative wound its way over and around a lot of dead test subjects and many victims of good intentions. And, let’s be clear, pre-Hippocratic Oath science isn’t to blame for the entirety of the medical field’s disturbing body count. Doctors have continued performing a number of flawed procedures right up into the present, a fact that points toward the inevitability of eventually looking back on some of today’s more common procedures with horror.

Here are the formerly common procedures we know look at with horror.

Trepanation

For early medical professionals, afflictions of the head as varied as epilepsy, migraines, and possession by otherworldly demons were relatively easy to treat: Just drill a hole in the skull. If something bad was taking hold inside the skull, they thought, what better way to to get rid of it than to give it a way out? The round holes left by trepanation — a word derived from the Greek trypan, “to bore” — have been found in skulls over 7,000 years old. Ancient Egyptian, Chinese, Greek, and Roman societies all seemed to practice this form of primitive neurosurgery. The Inca, were actually pretty good at it. While mechanical drills were used in medieval practice, there’s evidence that neolithic neurosurgeons simply scraped away bone using sharp rocks.

Crude though skull-drilling may seem, a highly refined form of trepanation is still occasionally used by modern surgeons attempting to relieve pressure in the brain caused by tumors or bleeding.

An advertisement for anti-acne radiation. Never trust a witch.

Acne Radiation Therapy

The Proactiv of the the early 20th century was, in fact, radioactive. Treating benign skin conditions such as acne and hemangiomas (clusters of blood vessels also known as “strawberry marks”) with radiation therapy — the same kind currently used to kill cancerous tumors — was common until the mid-1970s, when researchers began to suspect that the radiation was actually causing more serious health issues. Unfortunately, they were right: Women who underwent this extreme beauty regime were later shown to have an increased risk of breast cancer.

Electroshock Conversion Therapy

Electroshock therapy to “cure” lesbians and gay men was used until 1973, when homosexuality was officially removed from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the bible of the American Psychological Association. Before then, “conversion therapy” — also known as “reparative” or “ex-gay” therapy or “social orientation change efforts” — often involved the use of electric shock.

Psychologists would administer jolts of electricity to people — sometimes directly to the genitals — while showing them images of same-sex individuals in various states of undress. The fucked-up thinking behind this was that as the “patient” learned to associate arousal with searing pain, homosexuality would be stamped out in him or her.

While electroshock techniques are no longer used in the U.S. (it is still known to be used in China), psychology- and drug-based conversion therapy — championed by ultra-heteronormative organizations like the National Association for Research & Therapy of Homosexuality — unfortunately, still exists in America.

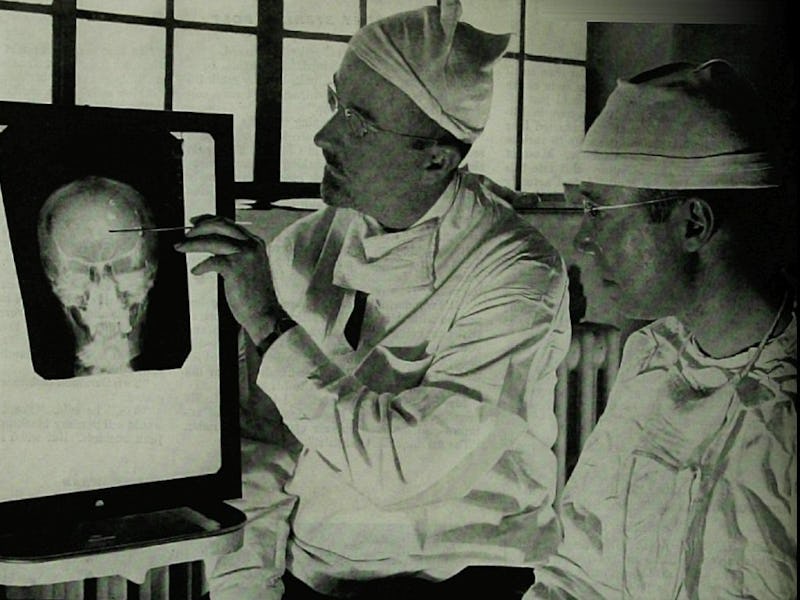

Lobotomies

Similar to their trepanation-happy forebears, early 20th-century neurosurgeons believed the best way to fix illnesses in the brain was to simply cut out parts of it. No matter that they didn’t know what regions of the brain were linked to specific functions (we still haven’t figured that out yet); as early as 1935, physicians were intentionally killing white matter (they were originally called “leukotomies,” after the Greek words for “cutting” and “white”) to cure mental illnesses as varied as schizophrenia and depression.

Did they work? Sure, they caused some drastic personality changes, which is to be expected when you cut out a chunk of the brain. Unfortunately, but not unexpectedly, they also often ended in death. The practice famously fell out of favor in the U.S. when a botched prefrontal lobotomy left President John F. Kennedy’s sister Rosemary in a state of permanent brain damage.

Radical Mastectomies

Surgeons treating breast cancer around the turn of the 20th century used massive steel jaws to amputate not only the entire breast, but also the pectoral muscles and lymph nodes attached to it — just to be safe. While these “Halsted” surgeries, introduced in 1894, were pretty brutal, they were a step up from even older techniques based on cauterization or amputation. These surgeries were considered routine until the 1980s when they began to be phased out in favor of less invasive surgeries that involved minimal disfiguration.

Bloodletting

Distilling life into four basic “humors” — blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile — Hippocrates, father of modern medicine, invented a system of physical checks and balances that largely revolved around spilling these anatomical liquids when their (highly arbitrary) ratios were off, a process thought to be inspired by female menstruation. Copious amounts of blood, thought to be the most important of the humors, was drawn, cupped, leeched, lanced, and cut out of patients for pretty much every medical reason conceivable.

Bloodletting as a miracle therapy continued long after the humor system was thrown out; the red-and-white striped barbershop pole, originating in medieval England, represented the blood and bandages that barber-surgeons handled during everyday bloodletting procedures. Eventually, even George Washington succumbed to this spurious medical practice; he’s thought to have died of bloodletting-induced shock. Physicians didn’t begin to question its use until the early 1800s, when French researchers thought to actually examine the medical records. Eventually they found that — surprise — bloodletting wasn’t really all that effective.

Still, Hippocrates wasn’t entirely wrong. Bloodletting (often using leeches) is still used in rare medical situations where there’s a scientific reason to get blood out, such as having too much iron or too many red blood cells floating around in the veins.