How to Fix a Game That Everyone Hates

How listening to marginalized voices helped sidestep abuse and saved a doomed app.

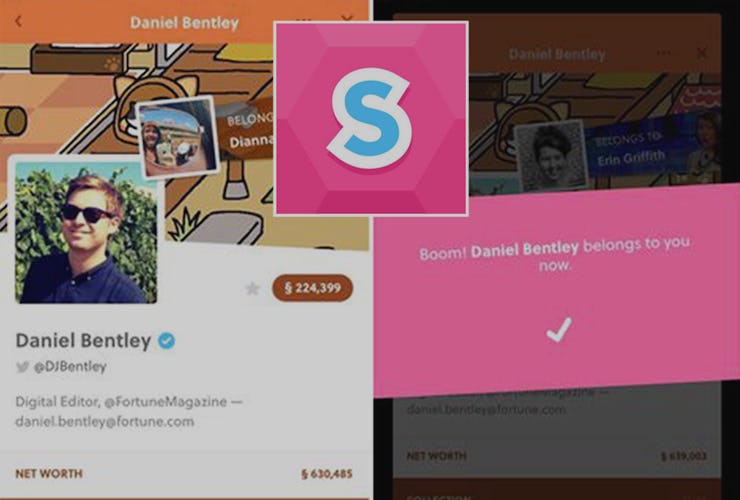

Back in January, an app-based game called Stolen launched in the iTunes store. I remember hearing about it secondhand, through watching social media backlash rain down upon the developer. It took nearly an hour to even figure out what the app was, I just knew — and this was all that I knew — that everyone in the world hated it.

Once I loaded it up, it was pretty easy to see why.

Stolen was a game based on the idea of owning and trading social media profiles. It’s a very cute idea if you happen to forget that people really hate the idea of being owned and traded. The idea practically defines “problematic,” but it was also easy to see how a developer could build this with the best of (oblivious) intentions.

The world demanded Stolen shut down. Stolen responded by offering people the ability to opt-out of inclusion in the game. This made the world much, much angrier at Stolen. There’s an excellent interview here between a reporter who learned of the game when she had been “stolen” and immediately contacted the developer’s PR to demand answers.

Stolen was pulled from the iTunes app store soon after, on January 14. Now the game is back, but in a much different form.

Yesterday, The Verge reported on the surprise release of Famous. Famous is the exact same game as Stolen, except for the following:

“Famous is different from Stolen in two important ways. One, the game is entirely opt-in: unless a person joins *Famous&, you’ll never see them in the game. Second, the app has dropped its off-putting language related to ‘stealing’ and ‘owning’ people. Instead, you ‘become their biggest fan.’ What used to feel uncomfortably like a slave auction is now depicted as a show of support.”

I’ve never been more shocked to see a game transform. What was once the subject of visceral rage for so many people is now a cute project — with an opt-in feature — that I can’t wait to download.

One of the key players in helping redevelop and relaunch the game is game designer and Crash Override Network overseer Zoë Quinn. She reached out to the Stolen team in the middle of its original backlash to let them know that their app was enabling harassment, but wound up getting invited to consult on fixing the game. I sat down with Quinn to ask how the games industry can do better at listening to marginalized voices, and how that openness can lead to successful changes that make life better for everyone.

What was your first impression of Stolen?

Oh man. My first exposure to it was an article between them and this journalist. The journalist was trying to explain to them what was wrong with the app and ended up using me as an example, so I was watching these two people discuss the ethics of buying and selling me. So you might imagine my first impression was recoiling from my laptop in horror. So many things seemed wrong with what they were trying to do, despite the founder seeming like a generally nice, if naïve, person. I was worried it was gonna be Peeple all over again. I immediately opted out. Well, I was honest about my distaste for what they were doing and begged them to scrap the app all together.

So you got in touch to offer to consult? Or just to offer some friendly advice at first?

Nah, nothing like that. I saw a few days later that they’d actually removed the app from the store and completely apologized without doing one of those weaselly “sorry if you were offended” things. This surprised me: I might sound jaded, but that’s such a rarity in Silicon Valley and was totally unexpected, especially after sinking so much time and money into something. It was heartening to see real people at the helm. So, naturally, my next thought was, “Oh, man, those real people did just piss off the internet. I hope they’re OK,” because I know how these things can get out of hand quickly.

So, I reached out to the personal account they’d given me and was just like, “Hey, I saw you removed the app. Thanks for doing the right thing. Also, are you OK? I know how intense things can get out here and I do run an anti-online abuse organization, so if anything is getting scary, don’t hesitate to reach out.” He seemed really touched by that, and asked if we could talk more about future plans so they’d never make a mistake like that again. I met with [founder] Siqi [Chen] a few weeks later as just an informal chat and dropped some general info on him. He seemed horrified and took notes, then proposed we establish a paid, working relationship going forward. He was able to know how much they don’t know with the best of intentions, and saw value in having me around — and even surprised me by insisting they pay me for my time and knowledge, because they saw it as so valuable and important.

So where did you start to steer the game? When was there a breakthrough that was like, “There is still something here; we just have to do it right”?

I am a recent addition to the team in a formal capacity, but during that first informal meeting I did dump a bunch of information on Siqi’s head — which he took notes during and seemed very engaged. That seemed to be the turning point, where he realized that they weren’t experts in online abuse, nor could they try to be, and asked me to get involved in a consultancy capacity. But, as with any consultant, all I can do is share advice and make suggestions. It’s ultimately up to them if they take that advice.

In terms of listening to the community’s complaints, do you consider this a success? What’s the takeaway other people should get from this?

I consider it an exemplary first step in a lot of ways, at least in terms of once things have already gone wrong. Ideally, it’d be nice to see more companies thinking critically and engaging experts before launch so there is less potential for harm. If someone has messed up and seeks decisive action taken to correct errors — and tangible investments, both financial and otherwise — to try to not make those kinds of mistakes again, it’s a pretty damn good way not only to try to make right with the world, but to make sure that you make something you can be proud of, as well.