Marvel's 'Civil War' Tried Poetry With Japanese Internment and Missed

Comics shouldn't shy away from serious issues, but, wow, was this off the mark.

Though Marvel’s 2006 Civil War comic was a mixed bag critically, and was marked by an anticlimactic ending, 10 years later, it’s popular among fandom by concept alone. It afforded fans front row seats to great action under the guise of a meaningful metaphor, and hopefully Captain America: Civil War will make up for the book’s shortcomings. But there’s one shortcoming best left entirely forgotten.

On February 19 in 1942, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 allowing the U.S. military to incarcerate 120,000 Japanese-Americans at the height of World War II. This moment in our nation’s history remains a black stain where fear and prejudice trumped (so to speak) the freedom and liberties that should be afforded to all citizens and fellow man.

After 9/11, paranoia reached fever pitch again, resulting in measures like the PATRIOT Act. Marvel aimed to be at the center of the conversation by pitting superheroes and their inclination to punch things — and each other — for ideal liberty. Civil War began when a superhero fight causes collateral damage with a massive death toll in the hundreds. The U.S. passes the Superhuman Registration Act compelling masked heroes to reveal their identities and register with the federal government. Accountability, liberty, privacy, and invasive powers of government were the thematic muscles to Civil War and were as heavy-handed as the Hulk’s high five. Almost all of Marvel’s books that year were devoted to the universe-shattering event.

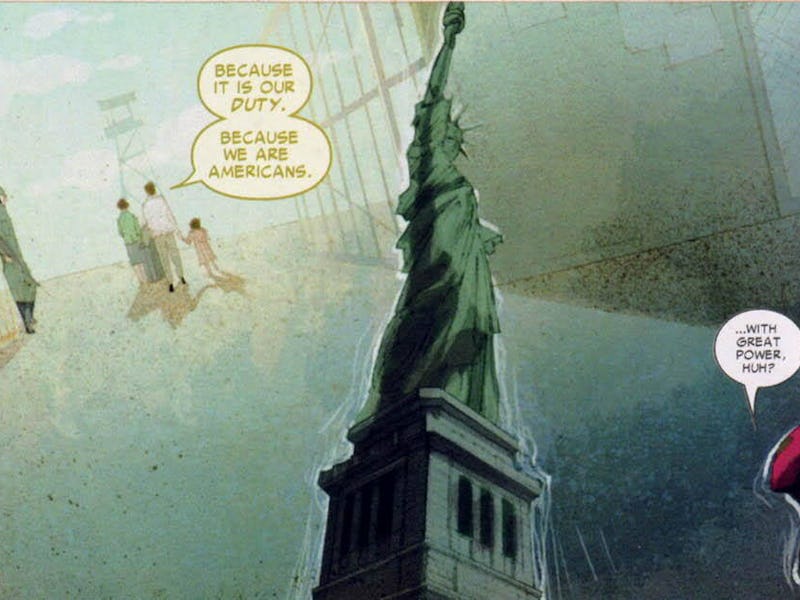

Civil War: Front Line was a new series conceived as a collection of vignettes that explore deep into the Registration Act. In the book’s first issue, it contained the three-page “War Correspondence” illustrated by Kei Kobayashi which drew lines of Civil War to the very real Japanese-American internment. In it, a father and his family are bused into the camp while an anonymous poem narrates their journey. Sharing panel space is Spider-Man, in 2006, having a crisis of faith.

“With great power, comes great responsibility.” Spider-Man is torn about whether he should reveal his identity in a symbolic gesture that implies registration is right. Spider-Man struggles if his “great power” as one of Marvel’s most recognizable includes swaying opinion for a greater good, especially when he doesn’t know what the greater good is.

In the last page, the father, looking up at a watchtower, tells his daughter why they’ve complied: “We are helping the war effort. Because it is our duty. Because we are Americans.” Meanwhile, Spidey looks up at a dividing Statue of Liberty. In the intertwining Civil War #2 and Amazing Spider-Man #533, Spider-Man unmasks to the public revealing himself as Peter Parker.

While meaningful in its purpose and sporting breathtaking art, “War Correspondence” flopped in its execution and divided a lot of readers. Internet commentators of 2016 deride the word “offensive,” but readers 10 years ago had no problem labeling the story with the “O”-word.

“That’s not where I got offended, though. One-sided debate is tiresome and disappointing,” wrote comics blogger Mark Fossen. “It seem to bears [sic] little relation to the story (there are no Superhero Internment Camps being proposed in Civil War), and feels wildly inappropriate and tactless. Using the pathos of a firsthand account of one of America’s most shameful incidents to lend depth to Spider-Man? It’s heavy-handed, self-important claptrap that just about sent the book flying across the room.”

“As if that isn’t offensive enough,” remarked Graeme McMillan of the Savage Critics, “The way that the internment camps are treated, with a Japanese father explained [sic] to his daughter that they’re moving to a new home because it’s their duty as Americans to help the war effort … just adds insult to insensitive injury.”

The biggest point of contention readers had was the issue’s preamble that was criticized as weakly straddling a “middle” perspective. Here it is, written by Paul Jenkins:

“In the interest of fairness, it can be noted that while they provided very sparse accommodation, these relocation centers had the highest live-birth rate and the lowest death rate in wartime United States. The Japanese in the centers received free food, lodging, medical, and dental care, clothing allowance, education, hospital care, and all basic necessities. The government even paid travel expenses and assisted in cases of emergency relief.”

“Hey, I wish I’d been able to have been ‘relocated’ to one of those wonderful, safe, centers back then!” McMillan wrote. “Utterly, completely, shameful.”

In reviewing the issue for Comic Book Resources, Brian Cronin wrote: “It was hyperbolic, it was silly, it was just a bad, bad idea. Nice art, though.”

On the other side, some readers found the story resonant with, yes, “nice art.”

“The thing is, it actually kinda works,” writes Charles Emmett in a collected review for Comics Bulletin, “I like the art a lot … and the poem is moving. It also does (kinda) tie into the greater theme of Civil War by examining how much of your liberties you should give up for your country. While it doesn’t offer any sort of resolution, it does make the reader wonder.”

“It feels slightly inappropriate to compare one of the worst violations of civil liberties in American history to spandex-clad superheroes. Still, it reinforces Spider-Man’s willingness to sacrifice some of his own freedoms for a greater good,” wrote Sam Kirkland in Comics Bulletin.

Ultimately, “War Correspondence” does paint a troubling portrait of perspective on Japanese-American internment. While I’m personally not against comic book superheroes blatantly taking a side over who had the “right” side in history, the father’s dialogue, “Because we are Americans,” romanticizes the troubling model minority myth that plagues the Asian-American psyche.

It is some great art though.