In Apple vs. the Government, It's a War for Precedent

Two cases that may illuminate whether Americans place more value on antiterrorism than they do privacy.

The U.S. government is attempting to coerce Apple into disabling a valuable security feature on the San Bernardino shooters’ iPhone, and the judge in that case ruled Tuesday that Apple must cooperate.

Which makes this case one of the “most important” technological-privacy disputes in recent history, prompting plans for protests in several big cities.

This case is concurrent with another, pending in New York City, in which Apple has the higher ground. And one of the two cases will set a valuable standard for cases to come.

The Motives of the U.S. Government vs. Those of Apple

Apple remains stringently opposed to so-called “backdoors” that the government could use to access an iPhone or other device. As a result, Tim Cook and co. are high-profile martyrs for privacy rights. (Cook is also a wise CEO, insofar as this gamble is already generating public trust for Apple.)

iPhones are equipped with a “10-tries-and-wipe” feature: if you attempt and fail to gain entry into the device 10 times, the data will self-destruct. This is the last thing the government wants to happen, as this is a major terrorism case and this data has the potential not only to seal the deal but also to set a legal precedent.

On Tuesday night, Cook released a letter to customers in which he attempted to justify Apple’s refusal to cooperate with the government. In short, Apple would not just be making an exception to a longstanding no-backdoors rule: Apple would be facilitating a backdoor that, it fears, the government would be able to enter whenever it wished, and — in so doing — would set a “dangerous precedent.”

Cook argued against the government’s suggestion that “this tool could only be used once, on one phone,” saying that “that’s simply not true.” He elaborated:

Once created, the technique could be used over and over again, on any number of devices. In the physical world, it would be the equivalent of a master key, capable of opening hundreds of millions of locks — from restaurants and banks to stores and homes. No reasonable person would find that acceptable.

Here’s how Edward Snowden reacted to Cook’s words:

The government, along with a sizable contingent of Americans, thinks it’s unfathomable that a tech company would resist any efforts that could lead to the conviction of a suspected terrorist. (And, as Snowden’s leaks demonstrated, most major tech companies do not resist such efforts.)

Thanks to the government and Tim Cook, we now have ourselves a center-stage, in the spotlight, American-idol style showdown. The two competitors: Privacy and Antiterrorism.

The San Bernardino shooters.

A Lengthy and Ongoing Dispute

This is not the first time that Apple has clashed with the government, though it is certainly the highest profile, most volatile case. In October, 2015, in the hearing “In Re Order Requiring Apple, Inc. to Assist in the Execution of a Search Warrant Issued by This Court,” Apple was initially asked to make exactly this exception by Judge James Orenstein of the Eastern District of New York. The government leaned on the All Writs Act — which, in its original form, dates back to the year 1789 — attempting to make an argument that the statute can inform such intricate privacy matters.

In this (still-pending but relatively unpublicized) case, the defendant pled guilty to drug and conspiracy charges. The prosecution — the government — still wanted to invoke the All Writs Act and still wished to gain access, via Apple, to the defendant’s iPhone 5S.

Apple’s argument against this measure took on a different tone within the confines of that case; the argument, instead, revolved around Apple’s business’s reputation:

Apple has taken a leadership role in the protection of its customers’ personal data against any form of improper access. Forcing Apple to extract data in this case, absent clear legal authority to do so, could threaten the trust between Apple and its customers and substantially tarnish the Apple brand. This reputational harm could have a longer term economic impact beyond the mere cost of performing the single extraction at issue.

The government, in the San Bernardino case, is currently attempting to lean on the same law — the All Writs Act — and Judge Sheri Pym, in the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California, ordered that Apple cooperate.

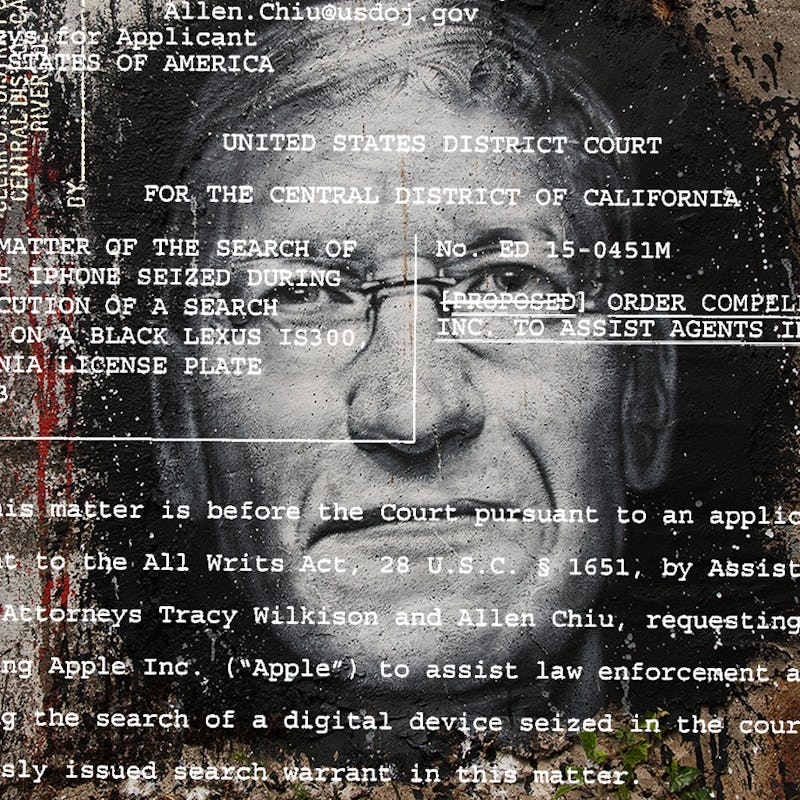

Tuesday's court order.

Judge Orenstein, in the 2015 case, wound up expressing an opinion in the government’s arguments in light of Apple’s brief; he argued that granting their request would be akin to “asking [Apple] to … work for [the government].”

A look into the government’s arguments in that case is informative:

In this case, bypassing the passcode to access the data covered by the Court’s search warrant without risking the permanent loss of that data requires a combination of information in the company’s possession, equipment and facilities at its headquarters, and technical assistance — all of which are within the purview of the All Writs Act.

The relevant iPhone privacy setting.

And, as in the San Bernardino case, the government wanted to gain entry into the alleged criminal’s phone — and would’ve used a “hacking tool” were it not likely that the data would then be destroyed:

Specifically, the [hacking] tool, which serially tests various passcodes until detecting the correct one, could activate the “erase data” feature of the iPhone and render the data in the Target Phone permanently inaccessible. By contrast, in this case, Apple has the unique ability to safely perform a passcode bypass on the Target Phone without risking such data destruction.

Judge Orenstein was not clear on why the invocation of the All Writs Act remained necessary, given that the defendant had already pled guilty, so he questioned the relevancy of the government’s requests. Apple, unexpectedly, took the prosecution’s side, arguing that the applicability of the All Writs Act should still be heard: “Apple agrees that this matter is not moot,” Defense Attorney Marc Zwillinger wrote.

The War for Precedent

That request, on behalf of Apple, occurred last Friday, February 12. Apple’s notion seems to have been that, if they could get this district court to establish a legal precedent in favor of encryption, similar prosecutions down the line — like the San Bernardino case — might have a harder time ruling another way.

Here’s Zwillinger:

Resolving this matter in this Court benefits efficiency and judicial economy. The question of whether the All Writs Act can properly compel a third party like Apple to assist law enforcement in its investigative efforts by bypassing the security mechanisms on its device has been fully briefed and argued. The Court is thus already in a position to render a decision on that question. Doing so would be more efficient than starting the debate anew when the government attempts to use the same methods and make the same arguments in another court, particularly where both parties agree that this matter is not moot.

Now, it appears, the government is making moves across the country, in California, with what could be a less-privacy-friendly judge on a much bigger stage: a nationally-known terrorism case.

The war for precedent begins. Both cases are taking place in district courts, and so any decision will be used as guidance in similar cases. And even though this precedent may not necessarily transfer across different jurisdictions, both sides would no less be able to trumpet their victories.

If you’re concerned about your own privacy, and would prefer to avoid this entire debacle, check out six alternative messaging apps that ensure your security — messaging apps that even a government-induced court order wouldn’t penetrate.