The Retro Romance of Space Valentines Hid the American Anxiety of the 1950s

"It would make perfect sense to put Valentine's, space, and school children together."

In 1962, five years after the launch of Sputnik and seven years before humans walked on the moon, President John F. Kennedy addressed a group of politicians, scientists, and students at Rice University.

“The exploration of space will go ahead, whether we join it or not, and it is one of the greatest adventures of all time,” Kennedy told the crowd. “Well, space is there, and we’re going to climb it, and the moon and the planets are there, and new hopes for knowledge and peace are there.”

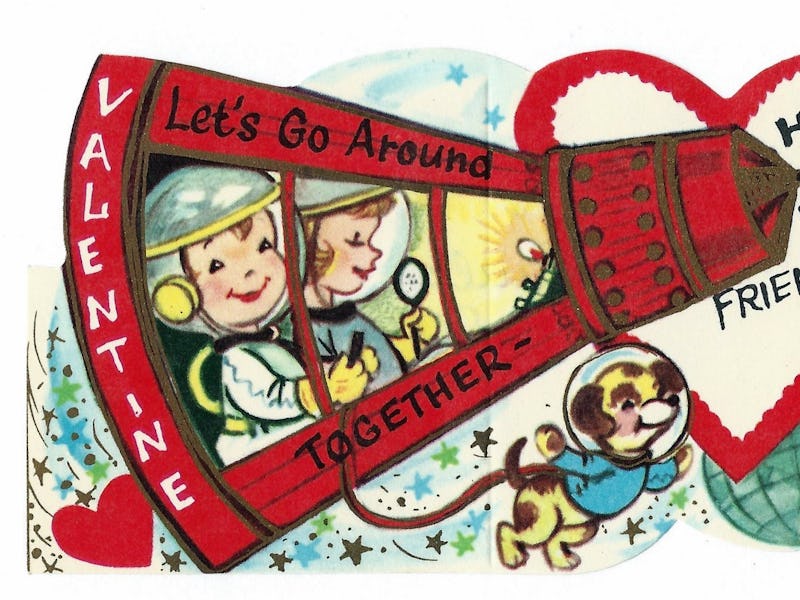

Kennedy’s sentiments towards space were romantic — the final frontier was widely regarded as the most exciting adventure left for humankind. This romance of big dreams and possibility trickled into many conduits of the Space Age, but perhaps none quite as charming as the space Valentines.

The peak of the Space Age is generally considered the mid-1950s to the late 1960s, built off the momentum of the invention of liquid-fueled rockets in the 1930s and the resulting boom of interest in space-minded pop culture.

An obsession with the future and the technology that would get us there gripped the United States and seeped into almost every cultural artifact: fashion, architecture, toys, art. Walt Disney employed spaceflight consultants when designing the rocket ship rides of Tomorrowland in 1955, and songwriter Bart Howard’s “Fly Me to the Moon” became so popular, he was able to live off the royalties for the rest of his life. Sputnik I, the first artificial satellite successfully put into orbit, kicked off a cultural flurry like very few inanimate objects before or since.

“For me, the early Space Age intertwined with a sense of youth’s almost limitless possibilities — the excitement of discovery, the allure of adventure, the challenge of competition, the confidence of mastery,” writes historian Emily Rosenberg in NASA’s Remembering the Space Age. “Transcending Earth’s atmosphere and gravitational pull so stirred emotions that space exploration became an intense cultural reoccupation.”

While their parents became consumed by more sinister Cold War fears, children reaped the benefits of Space Age design. Children’s playground equipment turned into rockets and faux Moon surfaces; Baby Boomer kids read space-themed comics and listened to space-themed radio dramas. And a perfect storm of education reforms and a penchant for celebrating Valentine’s Day ensured that kids in the sixties were sharing Valentines reading “You’re out of this world” and “There’s space in my heart for you!”

“In the 1960s Valentine’s Day was very much something that was celebrated in schools across the country,” cultural historian Robert Thompson tells Inverse. “And what else was going on in school at that time? Kids were following the space race, sometimes as part of the curriculum.”

Thompson, the director of the Bleier Center for Television and Popular Culture at Syracuse University, says that anybody in elementary school in the 1960s could probably describe a scene where, on rocket launch days, their teacher would roll out a cart with a television on it so the class could participate in the countdown.

“It would make perfect sense to put Valentine’s, space, and school children together,” Thompson says. “Especially because Valentines are almost like an empty slate — they’re a good way of finding what is currently in the psyche of America. The 1960s were a period of time where the story of space is very central in the American heart and soul.”

In hindsight, Sputnik’s shadow amounted to an urgent call for American STEM education to head off the Soviets. But space-centered curriculum in the classroom was slow to emerge. President Dwight Eisenhower originally opposed further federal aid to education. As the USSR surged, Americans questioned whether their children were in fact prepared for the future. This spurred a “great fever of education reform,” according to Rosenberg, that ultimately pushed Eisenhower to pass the National Defense Education Act in 1958. That allocated a billion dollars over the course of seven years to teach skills “essential to the national defense.”

These anxieties are embedded in the Valentines of the era, if you look beyond the romanticism of adventure. Thompson bring up the point that “you’re not going to make mushroom-cloud Valentines” and it’s true — the astronaut-helmet wearing boys, girls, and kittens don’t really give the impression of satellite-derived bombs.

I asked Thompson if he thought there was something inherently romantic about space and he paused before responding yes — but not in a “kissy-kissy” way.

“The final frontier is a romantic concept, and space has often been the backdrop to romantic interludes, kissing under the stars and that sort of thing,” says Thompson. “But again these aren’t Valentines of galaxies, focused on the mystery of space. These are all about the technology of conquering space, which is kind of anti-romantic.”

They are a stark contrast from, say, the Valentines pushed by the European Space Agency last year of nebulas and Orion’s belt. They’re also different than the Star Wars Valentines and tattoos that elementary school kids are grabbing up in 2016.

Margaret Weitekamp, an author and the curator of the Social and Cultural Dimension of Spaceflight Collection at the National Air and Space Museum, tells Inverse that while rosy-cheeked astronauts have faded to kitsch, space continues to play an important part in people’s romantic imaginations.

“Space in most the 1950s was literally empty and new,” Weitekamp says. “Now we live in a world where things in our everyday lives are assisted and governed by satellites that are in permanent orbit around this planet.”

The aerospace industry has matured, and our pop culture reflects that. Weitekamp notes that the 1950s and 1960s were a unique age where the fantasy and reality of space flight essentially merged. Today that fantasy lives through a resurgence in science fiction, while the space industry has rapidly grown.

“We’re seeing more different kinds of space exploration, in reality, than ever before and perhaps the depth and variety of what is happening right now doesn’t translate into what people are going to want to put on a Valentine,” says Weitekamp. “But I don’t think it’s for lack of interesting, optimistic, and ambitious things that are being done.”