Holy Shit, This 'Firewatch' Game Is Goddamn Gorgeous

Campo Santo's new "walking simulator" 'Firewatch' is one of the best-looking games we've ever seen.

Meet Firewatch. Firewatch is pretty. Well. “Pretty” seems thoroughly insufficient to describe what Campo Santo’s Firewatch is. This is a game that builds a warm aesthetic throughout, presenting a world that is monumentally enjoyable to walk through and experience. But it doesn’t just look nice, it knows it looks nice, and it presents its beauty to the player as the essential mechanism for understanding the game: not shooting, not puzzle-solving, not even talking (although there’s plenty of that), just looking good wandering the world.

And here’s how Firewatch knows that: It gives players a camera. Early in the game, your character, Henry, comes across a disposable camera. If gives a quick little training on how to use it, and then suggests you take pictures with an indication that you’ll see them “developed” at the end of the game.

But the genius thing is this: The camera has only a set number of potential photos. You have less than two dozen opportunities to take the in-game photos. And sure, you could take screenshots by pressing F12 in Steam or the Share button on PS4. But those have the game interface overlaid, and there’s something special and almost analog about using the tiny game camera.

The disposable camera in 'Firewatch.'

It forces you to think about framing and composition. Which picture is exactly the one you want to take? Do you want that rock in front of you? It directly connects you to the game world, and for a game like Firewatch, this is absolutely essential. (There is also the ridiculous, hilarious, awesome option to buy physical printouts of the photos you took for $15.)

Fellow 'Inverse' writer Nicholas Bashore took more pictures of trees in 'Firewatch' than I did.

Firewatch is a prestige game about wandering through a national park, making friends over your radio, and uncovering a mystery. It’s not a “game” in the sense of having combat or dice rolls or strategy, but instead is a “walking simulator” — a term initially used to deride games like Gone Home or Proteus, but which instead has become ironically endearing.

This type of game is built around level design — making spaces that the player can inhabit and examine and move through successfully. It’s no surprise that, for example, Gone Home was made by ex-Irrational employees, the company that made BioShock, one of the most impressive games of its era for environmental storytelling, beauty, and effectiveness. Take lessons learned in those areas, and apply them to just movement and narrative — no shooting — and you get this genre.

Everything about Firewatch is about creating this sense of place, and anchoring the player character to it. If there is a challenge to the game, it’s about finding the place to go and figuring out how to get there, requiring heavy use of the in-game map. That map looks like this:

The map in 'Firewatch,' which looks oddly like the one from Ubisoft's classic shooter, 'Far Cry 2.'

It’s part of the game world. The same button you use to focus your sight on things in the game world is the button you have to use to look at the map in detail. It’s also a deliberate homage to one of the most critically-beloved games of recent years, Far Cry 2 and its map. Much like the disposable camera, the in-world map is a deliberate minor annoyance that holds the player’s attention on things that are normally treated as conveniences.

But Firewatch’s biggest aesthetic strength is how it deals with light. The national park you wander through isn’t all that big, and you’ll cover the same ground two or three times over the course of the game, if not more. But it always feels different, because Campo Santo deploys different lighting each time. Here’s a clear, bright view of Jonesy Lake:

Jonesy Lake in Campo Santo's 'Firewatch.'

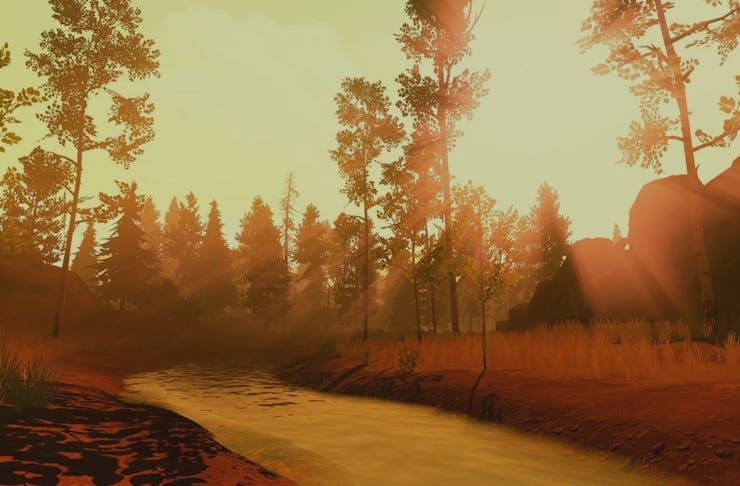

And then the meadow that leads to the lake at a different time in the game, approaching sunset, with smoke from the nearby fires adding to the haze.

Sunset in one of 'Firewatch''s meadows.

This stuff is programmed into the game story, as opposed to a natural day-night cycle. The latter would be cool if it worked, but embedding it directly into the game allows Firewatch to maximize the artistic impacts of time of day and weather to synchronize with the story. And, well, look how fucking pretty this game is. Goddamn.