Features

Can laser light therapy actually cure pain? We wanted to find out.

Proponents of the technology claim it can get people off of opioids, improve their sex lives, and make them smarter. Critics say it's bunk.

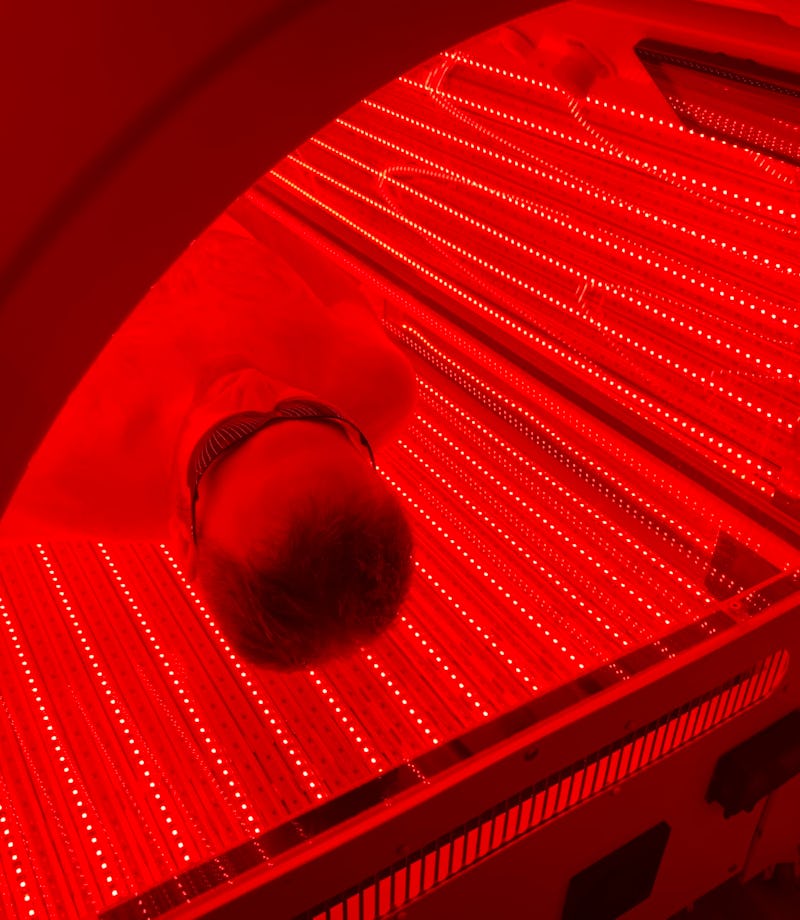

Before entering the pod, I strip off all my clothes. The room is dark, lit only by an electric candle. I put on a pair of plastic safety glasses. Then I climb inside what looks like a tanning bed from the future, reach up to close the hatch, and press the green start button.

The pod lights up with brilliant streaks of red. At first this is jarring and claustrophobic — I feel like I'm trapped in an MRI machine run amok — but then I relax, breathe deeply, and feel the warmth of low-powered lasers coating my body.

I am undergoing light therapy, which, depending upon who you ask, could be the future of healthcare or a total crock.

This is not the kind of light therapy where you buy a lamp to cure Seasonal Affective Disorder. This is a totally different beast. I’ve traveled to the Light Lounge, in Evergreen, Colorado (about 20 miles west of Denver), to learn about a treatment called photobiomodulation, aka PBM, aka “low-level laser therapy,” aka red-light therapy. With photobiomodulation, you climb into a pod and get bathed in low-wavelength light — between 650 and 850 nanometers, which avoids the harmful UV rays — for around 15 minutes at a time.

Photobiomodulation is meant to heal the body. PBM enthusiasts, citing hundreds of clinical studies, claim that it can reduce pain, tamp down inflammation, manage arthritis, assist with muscle recovery, treat ulcers, give you healthier and more attractive skin, help you recover from traumatic brain injuries, make you sleep better, soothe the wounds from cancer treatments, regrow your hair, boost short-term memory, sharpen your cognitive functions, and even (of course) improve your sex life.

But can it heal a toe? Two months ago, I tumbled down a flight of stairs and hurt my big toe. For days I walked with a limp, and even now I’ve been unable to play tennis or go running. My rehab strategies of resting, hoping, and binging on Netflix have been ineffective. Maybe it’s time for me to try and find the light.

Light Lounge sprung from pain. Its founder, David Martin, is a trim, cheerful, mid-fifties guy who likes to run ultramarathons. (This maybe isn’t that surprising; everyone in Denver likes to run ultramarathons.) A decade ago, while training for a race, he suddenly stopped breathing and feared he had a heart attack. Turns out his lung had collapsed. On the ambulance ride to the hospital, the EMT cut between his ribs, pried open his chest, and installed a breathing tube. The doctors later found a tumor, performed thoracic surgery to remove said tumor and his ninth rib, a process he says “felt like getting sawed in half.”Just one hitch: Martin is allergic to opioids, so when he woke from the surgery he vomited, choking on his own sickness, nearly dying once again. The doctors scrambled to clear his airways.

So he couldn’t take any pain medication. “I don’t know what to do with you,” Martin remembers the doctor telling him. “You’re going to have to grin and bear it.” On a scale of one to 10, the pain felt like a 20. For days, he writhed in agony. A friend of his, a chiropractor, told him about a laser therapist who could use her laser, somehow, to reduce the pain and block the nerve receptors. Martin didn’t buy it. What do you mean, a magical “laser”? Like Star Trek?

But he was desperate. So he agreed to try photobiomodulation.

For three days in the hospital, every two hours, Martin was treated with a hand-held PBM device. (You can get PBM either via the full-body pods or through a hand-held device, which zaps a more concentrated dose for treating wounds.) Martin says that after a few sessions, his pain plummeted from 20 to two.

And he had one question: Why didn’t I know about this?

While convalescing, he devoured research papers and combed through the hundreds of studies on PBM. Why isn’t this everywhere?! An entrepreneur, he sniffed a business opportunity. Martin bought two pods from manufacturer Novothor and installed them in a 53-foot trailer. He drove around Colorado and asked people to try the pods, first for free and then for a charge. He did this for years, gathering data. Martin estimates that between 2,500 and 3,000 people used his trailer pods. Often they wouldn’t feel a difference right away, but Martin says that of those who used the pods at least six times, 98 percent said they felt an improvement.

Okay, he thought. It’s go time.

A natural skeptic, I assumed PBM is all poppycock. I’m kind of basic: I like Western medicine. “Light therapy” reminds me of that time in Bali when I was dragged by a friend to the Pyramids of Chi for “sound healing,” where a man in a robe kept striking a gong that would cleanse my chakras, or something.

But I try to keep an open mind as I spend an entire day at the Light Lounge, curious about who — if anyone — is actually using this treatment. Spiritual healers? Reiki gurus?

Standing outside the doorway of the Light Lounge — which displays the sign “First Session is FREE!” — you can see the foothills of the Rockies, coated with snow. The waiting room smells of tea and oranges. There are three small rooms with pods, and soon the place is filled with a steady stream of customers. (They pay $165 for a three-pack, $195 for a 10-pack, or $165 for a monthly membership.)

The manager, Liz Weston, says they have 90 members, most of whom come three times a week, and a handful who come every day. (“People kind of get a little addicted to it,” she says.) Most seem to be over 50, and they’re generally here for pain relief. Plenty are true believers like Don, 67, who was told he needed two knee replacements. Then he tried light therapy: “My knees have not felt this good in five years.” The doctor, amazed, said he no longer needs the knee surgeries. Bonus? Don says he’s been sleeping better than he has in decades.

I hear all kinds of testimonials like this. Doug, a 62-year-old who still plays ice hockey, had osteoporosis in both hips, and a grade 2 separation in his shoulder. He says light therapy lowered his inflammation instantly. “I was only out of ice hockey for five weeks, and then I played in the championship game,” says Doug. (“We lost,” he adds.) There’s Karen, who has been coming six days a week to treat her eczema. Karen holds out her forearms to proudly show me her clear skin. “You should have seen these arms before!” Then there’s John, 72, who used light therapy to treat his stiff neck, and says he felt better “almost immediately.” Many tell me that they just feel better, period.

The Light Lounge customers are not the hippy-dippy folks I expected.

These are not the hippy-dippy folks I expected. No one speaks of chakras. No one pushes Qigong. These appear to be pragmatists — like the owner of a construction company or the CFO of a $40 million impact investment fund — who have been won over, sometimes grudgingly, by the results.

The Light Lounge is not the first clinic to offer PBM. Novothor lists around 100 locations that use their pods. Some chiropractors are now treating patients with handheld devices, and you can even buy them on Amazon (although the cheaper ones have lower power, and are thus potentially less effective). And PBM is beginning to be used by elite athletes. A few years ago, the NBA's Phoenix Suns, a team widely respected for having one of the most innovative training staffs, bought a Novothor pod. Defense specialist P.J. Tucker (now with the Houston Rockets) used the pod after his back surgery, and credits PBM for helping him return to the court. “I do Novothor almost every other day,” he said in a Novothor promotional video from a few years ago. “Once I started doing this, I… noticed the difference. I was feeling fresher. I was feeling like I could get that strength back in my legs.”

Some of the Suns use the pods for pre-game boosts, some for post-game recovery, and some ignore it altogether. Brady Howe, the team's head trainer, tells me that the basics of sleep, nutrition, and training are by far the biggest drivers of rehab and recovery, but that PBM has a role on the margins (“like the whipped cream on top”). It’s in the same category as alternate treatments like, say, underwater treadmills, or maybe interval plunges into cold and hot tubs of water. “I think [light therapy] plays a very small role in the grand scheme of things, but do I think it has a benefit?” He pauses. “I do.” He acknowledges this could be a placebo effect. “If the players believe it’s helping them, then it is helping them.”

Okay, fine, but what does the science say?

It all began with rats. In 1967, a Hungarian scientist named Endre Mester tried to use lasers to cure cancerous tumors, and he experimented on rodents. Mester had no luck curing cancer, but he noticed something baffling: when the rats — who’d been shaved for easier access to the tumors — were treated with low-powered lasers, their hair grew back faster. And not only that, the lasers seemed to cause their wounds to heal faster.

So for the last 50 years, researchers have tried to harness this power to treat humans. The science is less magic-wandy than you might think. For starters, there’s little debate in the scientific community that light can have an impact on the body’s cells. That much we know. Just as sunlight triggers photosynthesis in plants, certain wavelengths of light can affect the human cells of mitochondria, which I remember my high school biology teacher describing as the “mighty mitochondria” because they do all kinds of useful things: generate cellular energy (by creating adenosine triphosphate, or ATP), influence our metabolism, and help regulate cell growth. The theory is that when light from PBM stimulates the mitochondria, the increased energy gives something of a halo effect for both the body and the brain. How much of an impact — enough to make a difference? — is up for debate.

“PBM strengthens the mitochondria,” says David Caha, the president of Light Lounge, who patiently walks me through the science. “And that gives us all kinds of downstream effects.” Caha has a research background in cognitive science from the University of Colorado at Boulder, and says he only joined Light Lounge after being convinced by a mountain of studies. Caha, like Martin, is trim and athletic, and looks like he could run an ultramarathon tomorrow. “I was skeptical,” he tells me. “But you look at all of the studies, and it adds up.” He compares this to an alternative treatment that gets far more mainstream attention, cryotherapy. “Cryo doesn’t even compete,” he says. “ Not to put it down, but the data’s not there in the same sense that it is for light therapy.” (He later referred me to this study.)

One medical watchdog website says the research is “dotted with issues.”

It’s true that there are hundreds of studies suggesting a benefit of PBM (the Light Lounge blog links to many of them), and the studies generally agree that it’s safe and without side effects, but it’s also true that independent, objective medical experts have reviewed that body of research and come away unimpressed. Dr. Stephen Barrett, who runs the website Quackwatch, analyzed the studies and concludes “that LLLT [low-level laser therapy] devices may bring about temporary relief of some types of pain, but there's no reason to believe that they will influence the course of any ailment or are more effective than standard forms of heat delivery.” He notes that insurance companies such as Aetna, Cigna, and CMS do not cover PBM. In a similar vein, the medical watchdog website HealthybutSmart says the research is “dotted with issues” and finds that light therapy “seems to be beneficial to certain injuries and pathological conditions but the panacea claims currently made are not yet backed by research.”

I run the skeptical arguments by Dr. Michael Hamblin of Harvard Medical School, who heads up the Wellman Center for Photomedicine at Massachusetts General Hospital. Hamblin is an advocate of PBM — perhaps its most prominent researcher — and the editor of the book Advances in Photodynamic Therapy: Basic, Translational and Clinical (Engineering in Medicine & Biology). Hamblin is not surprised or deterred by the skepticism. “The way the mainstream medical profession is set up, you have to have large, randomized, controlled clinical trials to show a positive benefit for it to be accepted,” he says. “This is the foundation of evidenced-based medicine.” Yet trials like this tend to cost millions of dollars, says Hamblin, and companies in the photobiomodulation space, most of them small, lack these resources.

The Cochrane Reviews, from a global organization of health researchers, are widely regarded as the gold standard for vetting medical studies. Hamblin characterizes Cochrane’s position on PBM as “lukewarm.” In one review of LLLT on back pain, for example, Cochrane found the following: “Three studies (168 people) separately showed that LLLT was more effective at reducing pain in the short-term (less than three months), and intermediate-term (six months) than sham (fake) laser. However, the strength and number of treatments were varied and the amount of the pain reduction was small.” Providing ammunition for both skeptics and believers, Cochrane concludes that “there are insufficient data to either support or refute the effectiveness of LLLT for the treatment of LBP [lower back pain].”

Yet Hamblin says the evidence is growing. He says there are 40 clinical trials showing that PBM is an effective treatment for oral mucositis, a painful tissue swelling in the mouth that is often caused by chemotherapy. “This is now accepted by the regulatory bodies in Europe, and is now considered the standard of care,” he says. Hamblin’s current research is focused on photobiomodulation on the brain, as he believes there is evidence that it can be used in the cases of strokes, traumatic brain injuries, dementia, Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder. He thinks it can even boost cognitive function.

“I love skeptics! I want them to bring it on.”

Hamblin practices what he preaches. Every day, he straps a device to his head that bathes his brain in low-level lasers. Roll your eyes all you want, but there is indeed research showing that PBM can sway neural activity. A 2019 peer-reviewed study published in Nature’s Scientific Reports (a journal with a higher bar for academic rigor than, say, Goop) hooked people’s brains up to EEGs, applied light therapy, and found that “a single session of tPBM [transcranial PBM] significantly increases the power of the higher oscillatory frequencies of alpha, beta and gamma [waves].” Meaning that the light, quite literally, caused stimulation in the brain.

As for Martin’s reaction to skeptics? “I love skeptics!” he says cheerfully, reminding me that he himself began as a doubter. “I want them to bring it on.”

At my first session, before stripping off my clothes, I see a control panel where I need to select from a menu of “protocols” of different types of light therapy. The list, so long that it needs a second page, includes options like Balance, Jet Lag, Hangover, General Wellness, Maximum Output, Peak Performance (it’s unclear how “Maximum Output” differs from “Peak Performance”), Boost, Double Espresso (yet no single shot of espresso), Focus, Post-Workout, Rock Star, Spa Day, Skin, and Wedding Night. (“Wedding Night” — meant to help with sexual potency — indeed works, Martin told me with a chuckle.)

Understanding how (or if) these protocols work requires a deeper dive into the tech behind Light Lounge’s specific devices, made by Regen Pods. There are three variables in light therapy: the wavelength of the light, the power (or “dosage”), and whether the light is continuous or pulsing. As the co-founders of Regen Pods manufacturer Biophotonica, Ken Teegardin and Tom Rebman, explain to me, tweaking the combinations of these three variables will produce different responses in the cells, although it’s still not entirely clear — even to the experts — precisely which is the best configuration. (Teegardin says that the different manufacturers all claim that their settings are the best, and there’s something of a debate in the field.)

Some combinations seem to work better at reducing inflammation, some are better at boosting cognitive function, some at stimulating blood flow, and so on. In a clever bit of future-proofing, Regen Pods are designed so that the settings can be customized, recalibrated, and updated; if the science later shows that, say, it’s better to add a pulse to a given treatment, then the pods — via software updates — can adopt the new configuration. (This works much in the same way that Tesla owners, through firmware updates, can receive new features to their cars.)

It’s these different settings — to wavelength, dosage, and pulsing — that yield different PBM protocols at Light Lounge like Rock Star, Skin, or Wedding Night. And here my skepticism returns. Dr. Hamblin, the PBM research authority, tells me that there is indeed evidence that changing a variable like pulsing, for example, can be more advantageous for different treatments, but he’s wary of a menu of protocols. “Most of that is just hype,” he says, “as they’re trying to convince people that they’ve got some magic formula.”

The truth could be somewhere in the middle. Even if the bells and whistles of specific protocols like Double Espresso are marketing gimmicks, it’s still possible — perhaps even likely — that PBM is effective at treating the underlying inflammation. It’s also possible that because the field is still in its infancy, companies like Biophotonica and Thor Photomedicine (the maker of Novothor) will get better at calibrating the wavelength, pulse, and dosage, and in the future, perhaps — perhaps! — the treatments really will be revolutionary.

Last October, Martin testified before Congress on how PBM could be a pain-relief alternative to opioids, as did other authorities like James Carroll, the CEO of Thor Photomedicine. That idea is now being tested. Earlier in the year, Congress issued a $2.7 million grant to Shepherd University in West Virginia for the study of replacing opioids with PBM.

“I want to open 6,000 Light Lounges before I die.”

Is light therapy about to have its moment? Martin is counting on it. He plans to open 10 to 15 locations in the next 18 months, primarily in the Colorado area, and then expand nationwide. “I want to open 6,000 Light Lounges before I die,” he says. Harvard’s Dr. Hamblin is similarly bullish. In the future, he says, “I think every household will have at least one, maybe a few, photobiomodulation devices.”

I have a more humble goal: to heal my toe enough so that I can go running. I didn’t really feel anything on that first session. A few days later, on a Saturday, I chose the protocol Big Night Out. Not much progress on my toe, but I did end up staying up past 2 a.m., which, I’m sad to report, is well past my normal bedtime.

On the day of my third and final session, coincidentally, a friend invited me to join her runners club for a three-mile jog and then beers. (This is the kind of thing people do in Denver.) At first I said no — I can’t run, my toe is hurt.

Then I thought of the light therapy. Maybe this would push me over the edge? If it works for NBA players on the Phoenix Suns, maybe it will work for me? So for that last session, I chose the Pre-Game protocol. I have no idea if that protocol does anything different than Double Espresso or Big Night Out. Yet once again I got naked, climbed in the pod, and felt the red lasers cocoon me with warmth.

Did the toe feel better? It’s difficult to answer with confidence, in the same way it’s tough to answer the optometrist when the two vision settings look nearly identical and she says, “Which one can you see better, this one or that one?”

Maybe it improved a bit? Maybe not really? Maybe there was a bit of placebo action? I don’t know for sure. It’s also possible that I wouldn’t get the real impact until six sessions or more.

But what I can say with certainty is that hours later, for the first time in over two months, I laced up my running shoes and ran three miles. And I didn’t even notice my toe. I might not be a Rock Star, but I felt those long-forgotten endorphins you get from exercise, and I felt good, and I felt alive.