Body talk

I have one of the most advanced prosthetic arms in the world — and I hate it

Being a cyborg is cool right now, thanks in large part to gee-whiz media coverage. But actually using a bionic arm can really suck.

Lately, I have been thinking about getting a new arm. With the profusion of lower-cost and 3D-printed prosthetic arms on the market, I’ve been hoping to finally find one that fits well.

While shopping online, I land on the site of one of the dozens of new, high-tech prosthetic arm companies and pulled up some of their videos to get a closer look at socket designs. Instead, I get yet another example of what I call “prosthetic unboxing videos” so popular on TikTok and local news stations alike.

These videos are a cliché by now: young kids with missing limbs wiggling with joy as they unbox and put on a new prosthetic arm for the first time. In 2015, Robert Downey Jr. himself presented a then seven-year-old boy with a 3D-printed Iron Man–styled prosthetic arm.

These videos never show prosthesis users doing two-handed tasks. Instead, they do things most of them would only ever undertake with their other fleshy hand, like write or drink water. These videos, for the most part, exist to emotionally move the non-disabled viewer (that’s what we in the community call “disability porn,” folks).

Don’t get me wrong — I have been psyched about a new arm, too! But the media’s coverage of these new kinds of prosthetics is so focused on the initial joy or incredulity — on the idea that “lives are changed” — that they forget to ask if these hands are actually useful and what happens in the weeks and months after the unboxing.

Because every upper-limb amputee (acquired or congenital) has a unique body, their experiences with prostheses and the prosthetists who provide them vary dramatically, making user experience especially difficult to study. Upper-limb prosthesis user dissatisfaction is generally very high, with the majority of users in one recent study reporting very negative experiences. Recent studies report rejection rates — those at which people discontinue using their prostheses entirely — as high as 44 percent.

The average percentage is likely even higher among children because they more often will lose patience while learning how to control prostheses and experience greater discomfort with the weight. Even as prostheses have advanced to the point of becoming points of fascination on TikTok and the Forbes website, user satisfaction has largely stagnated in recent decades. Still, it should be noted that the rate of satisfaction of users of this new wave of prosthetic arms hasn’t yet been the subject of a large-scale study.

“People expect you as a cyborg to be able to punch through walls.”

In the meantime, we are inundated with clickbait tear-jerkers like “11-year-old flexes his new bionic arm.” If the endless media hype is to be believed, you’d assume high-tech prosthetic arms are turning people into superhumans. “People expect you as a cyborg to be able to punch through walls,” says Londoner Ashley Young, who has tested a smattering of the latest multi-articulating hands (prostheses with independently moving fingers).

I was born without most of my left forearm; prosthetists call me “short” because my limb stops almost immediately past my elbow. I was first fitted with a prosthesis at six months old, and I’ve been shoving my arm — ahem, “residual limb” — into a socket almost ever since. At that time in the early 1990s, doctors were telling the parents of limb-different kids that we should be fitted with prostheses as early as possible so that our brains would develop “normal” hand-eye coordination. I wore a simple, single-grip myoelectric for most of my childhood. It was bulky and had an extremely tight socket I had to force my “little arm” into using Aveeno hand cream. It gripped poorly and would sometimes glitch in the middle of class.

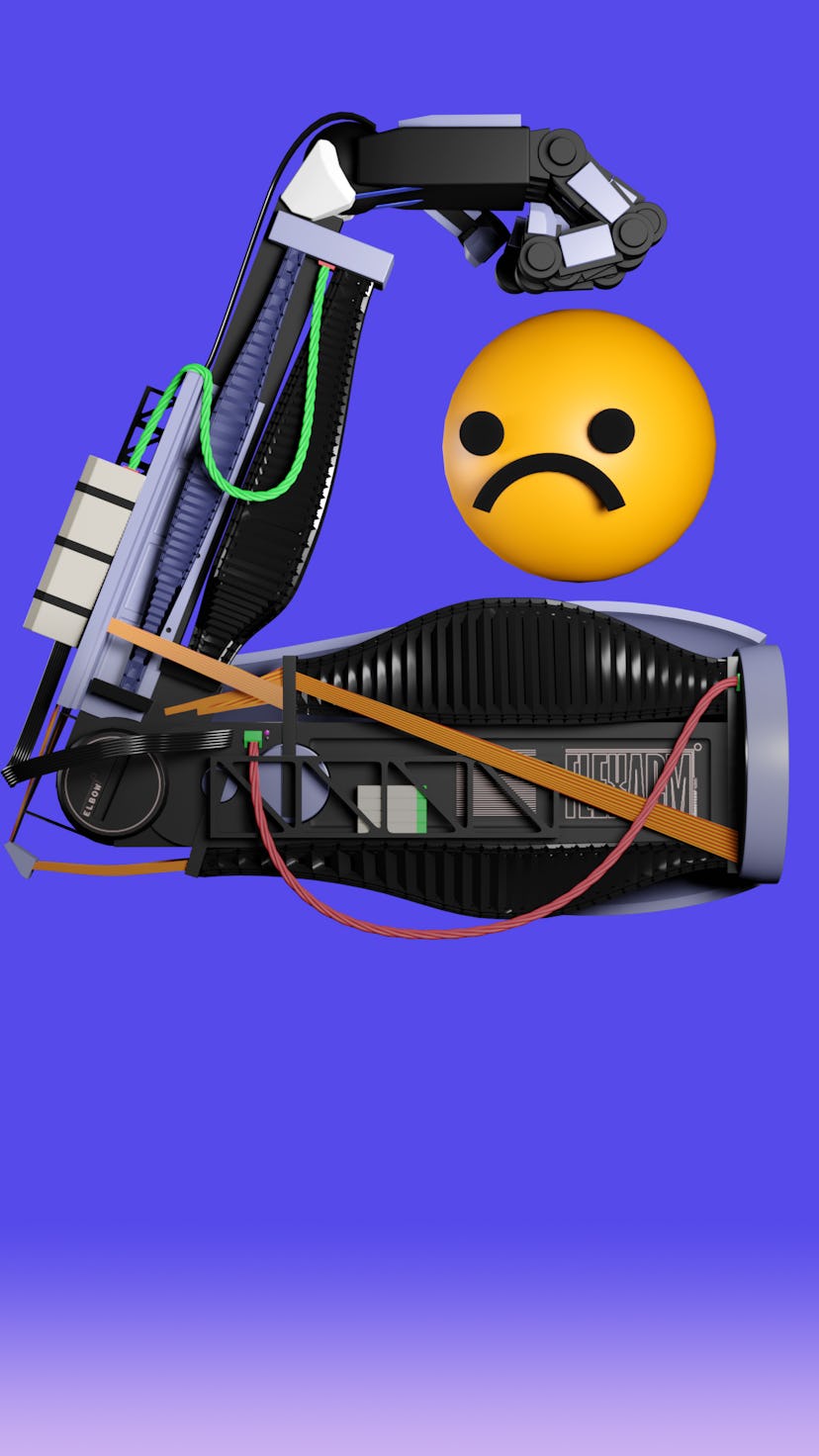

Eventually, I decided the weight and lack of functionality wasn’t worth it and switched to using a “passive,” or lifelike arm without any powered components. That is until 2018, when I was wowed by news reports about the Bebionic, the flagship model of powered hand from German company Ottobock. It has multi-articulating fingers, numerous grip modes, and is small enough to not look like the wearer has a Hulk fist. The news made it seem impossibly cool. After seeking out a new prosthetist, I got my first powered hand in over 15 years.

When my new, 21st-century arm arrived, I hosted an “arm party,” an absurdist celebration of the new device as well as a farewell for a pile of old, passive arms with broken silicone fingers held on with Band-Aids. We had cocktails with arm puns: Armageddon, Pink Armadillo. And we played prosthetic arm Twister during which you could use any of the old prosthetic arms in the pile to help you reach. We got high and set up a makeshift photo booth with a bedsheet so everyone could take surreal pictures with way too many arms.

It was the first time in my life my arms were fun and the basis for shared hilarity, not just me being weird. At the end of the night, the Bebionic — with me attached — cut the celebratory chocolate cake.

And that was one of the last times I ever used it.

Maybe it was because it felt heavy as hell. It was only three pounds or so, but three pounds feels like a ton to a limb that typically carries no weight, and the heft of the prosthetic hand pulled hard on the socket and made me sweat. In order to open and close, myoelectric hands require that you flex your muscles where sensors inside of the socket can detect your movement. There are typically only two “contact site” sensors inside the socket — this is called a “dual-site” system — so you need to cycle through a series of grip patterns by flexing twice in quick succession inside of the socket to get to the one you want.

The “power grip” (a fist) is cool, but, oh my God, trying to cycle through all the modes to find it is infuriating. (Did I mention that you cannot reprogram the hand to include more grip patterns without an appointment with your prosthetist?) In fact, everything about the Bebionic was exhausting. I’ve used it on and off on special days, but most often as a party trick: Wanna see me crush a can?

Prosthetic arm technology is still so limited that I become more disabled when I wear one.

Maybe I just realized that very few things in life truly require two “fleshy” hands to get them done, and that my new fancy hand still couldn’t compete with my own lifelong adaptations. Yet, there were some days I’d try it out for as many hours as I could. Overall, I found integrating it into daily movements actually surprisingly easy. I had spent my whole life watching two-handed people do fancy things like close a door with one hand and lock it with the other. Finally, I could do that too (though I was unable to pull off that mesmerizing dance of knife and fork that my steak-cutting friends are able to do). I was also able to hold a plate with one hand and snack and gesticulate with the other at a New Year’s Party once.

You know the only other time I could do these things? When I am not wearing any prosthesis at all.

Prosthetic arm technology is still so limited that I become more disabled when I wear one. There are very few, special tasks I can do better with it (case in point: using a potato ricer). But mostly what it does is helps me mimic two-handed people. I realized that my excitement about my new hand was mostly about being able to be something other than disabled — a cyborg. The day my prosthesis arrived, I tweeted a brief video of myself petting my cat with it, the hand’s rubber-lined fingers and palm snagging uncomfortably on the cat’s fur.

I was in the club now. The self-identified cyborg community is super-chic, all over the internet, and actually celebrated by the media, unlike the regular old disabled community. When did this happen?

Prosthetic arms and legs were long supposed to help you blend in with the four-limbed crowd and look normal. Then a shift occurred. In the wake of the war on terror and the countless American soldiers coming home with traumatic amputations, the U.S. government launched the Revolutionizing Prosthetics program in 2006 to develop a “neurally controlled artificial limb.” The U.K. also began to invest in similar prosthetic arm moonshots, and private companies soon took up the race to develop the first multi-articulating hand.

In the last decade or so, the visibility of high-tech prosthetic limbs has exploded, particularly in pop culture. Furiosa in Mad Max: Fury Road has a somewhat ramshackle but still futuristic-cool mechanical appendage. Captain America: Winter’s Soldier features such a capable cybernetic arm that it might as well just be a fleshy hand. The South African mining villain in Black Panther boasts a life-like prosthetic hand with a built-in sonic cannon. The upcoming Mortal Kombat reboot features a character with fearsome metal arms.

Meanwhile, Vogue has profiled models and fashionistas with cyber-chic prosthetic legs (always legs though, never arms — a story for another day). Today, both amputees and “congenitals” like me want prostheses that look robotic, that call out for attention. Cyborgs are having a moment.

Take, for example, Angel Giuffria, the cyborg actress whose credits include the 2019 indie film Synthesis and appearances in The Accountant (2016) and The Hunger Games (2014). She pops up on the front page of Reddit regularly. The cyborg identity has launched her internet stardom and has set herself apart in an industry that’s deeply discriminatory against people with disabilities. Angel says her multi-articulating, LED-lit, carbon fiber-coated hand is an extension of herself. She wears it outside of her house so that she knows she can do anything “the way” she wants to do it.

Often, that’s the way that allows her to be left alone. “If I’m at a restaurant and want to cut a steak, and I go to do it with my little arm, everyone’s gonna stare at me or offer to help,” she tells Input. “But if I do it with my prosthesis, nobody. Says. Anything.” Or, she adds, people will think it’s cool. Angel loves her customized bionic hand and what it enables her to do socially, even if she is able to do most tasks without it. (She did leave me with a weird tip: don’t go to Walmart wearing your bionic arm — for some reason people love to stop you to tell you how much they love your prosthesis there.)

There’s some truth to poet and disability activist Jillian Weise’s argument in her essay "Common Cyborg" that the nondisabled “like us best with bionic arms and legs…. They want us shiny and metallic and in their image.” Cyborgism often serves as a way to make other people comfortable.

The media narrative, says James Young — husband of Ashley and a cyborg himself — is designed to be reassuring to people: If you happen to, God forbid, lose your arm, “they” can replace it. “People want to make sure that the technology is out there that can remake you as you are right now,” he says.

James knows the typical media narrative all too well. After a horrific 2012 train accident left him missing his left arm up to his shoulder and part of his left leg, the video game maker Konami built him a completely custom Metal Gear Solid–inspired bionic arm that was “loaded with extras” like Wi-Fi capability and a detachable drone. The coverage of this project was the perfect encapsulation of the media’s obsession with the nexus of high-tech and heart-warming. Sample feelgood headline: “A bionic limb lifts a life.”

He says that all the “inspiring” stories of 3D-printed prosthetic hands have misplaced enthusiasm: “It’s going to break as soon as they walk into a wall on accident.” Even James’ sci-fi futuristic arm was bulky, difficult to put on, and quickly broke because its primary function was to look impressive. The prosthetics team substituted some components with bike parts as they rushed to complete the arm for a TV documentary. But it’s not just one-off promotional prosthetic arms that are limited by futuristic aesthetic expectations.

Even the most expensive and sophisticated prosthetic hands on the market today are still limited by their set of preprogrammed grips that mimic the function of a human hand. Ashley, who has part of her arm like I do, shares the feeling that prostheses can be more debilitating than enabling. And while both Ashley and James agree that it’s cool being a cyborg, these hands still struggle to provide the functionality of older, body-powered prehensors or “claws.”

These days, James largely uses the Ottobock Greifer, a kind of electric prehensor, which helps him do everyday chores — once he’s completed the cumbersome task of strapping the prosthesis to his torso. Since James was amputated at the shoulder, fit and control are the biggest hurdles. He tells Input that where there’s a real reason to get excited is in innovation in myoelectric control. There are new sensors and new technology able to record and learn multiple “contact sites” on your limb that can correspond to far more complex controls than “open” and “close.”

Such innovations are desperately needed. Some advocacy groups have suggested that the high rates of dissatisfaction with bionic limbs are primarily the result of the inadequacy of “dual-site” myoelectric sensor systems. But the media has little enthusiasm for the type of innovation that doesn’t focus on the way the bionic arm looks. “It’s hard to really communicate how fantastic something is without the visual aspect,” says James. Everyone wants to see the cool robot hand, but they don’t give much thought to the 16 complex sensors inside.

Meanwhile, what the mainstream bionic hand discourse leaves out is access. Myoelectric arms start at around $30,000, and most insurance policies will not cover them. Thanks to my extremely generous graduate student insurance, I paid $13,000 for my prosthetic arm, which was originally billed at $72,000.

For Alexis Hillard, the creator of the YouTube channel “Stump Kitchen,” the obsession with cyborgs is “continuing to drive that wedge between disenfranchised disabled people and those with money and power, creating a new ‘desirable disabled person.’” It seems that the majority of cyborgs out there are white and have some level of class privilege. In the U.S., which lacks universal healthcare, so many people don’t even have the choice to become cyborgs due to the prohibitive cost of prostheses.

Even if for most people myoelectric arms end up being more flash than function, that flash can improve mental health. Bilateral amputees and those amputated closer to their shoulders, especially, need the opportunity to try any new technology that comes their way. Every disabled person should have the opportunity to at least try these technologies, see how they might work for them, and discover something new about their bodies and their abilities.

“People have such rigid ideas about the human body.”

No matter what, being cyborgs isn’t saving us. The most disabling thing about missing my left arm is the way the world treats me, regardless of whether I put on a prosthesis for the day. “People have such rigid ideas about the human body,” says Sara Hendren, Professor at Olin College of Engineering and author of What Can a Body Do? “People wouldn’t make such a huge deal out of disability if they saw their own bodies as getting and receiving help when they need it.”

In other words, none of us is utterly independent; we are constantly receiving help from other people or from some tool or piece of technology. If more people saw this clearly, then prosthetic limbs wouldn’t be turned into “savior” devices by the media. My choice over whether to be a cyborg or not wouldn’t be so high stakes.

And when my prosthetic arm sucks — which it does — it would be just as cool to do things my way.

Maybe I won’t get a new arm after all.